Low Fermentation Diet: A Comprehensive Guide from Cedars-Sinai

Low Fermentation Diet: A Comprehensive Guide from Cedars-Sinai

Digestive health issues affect millions of Americans, with symptoms ranging from mild discomfort to debilitating pain. For many, finding the right dietary approach can make all the difference in managing these conditions. The Low Fermentation Diet, developed by researchers at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, has emerged as a promising solution for those suffering from irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), and other functional gastrointestinal disorders. This comprehensive guide explores the science behind this dietary approach, its implementation, and how it might help restore digestive balance.

Understanding the Low Fermentation Diet

The Low Fermentation Diet focuses on reducing foods that ferment easily in the digestive tract, particularly in the small intestine. When certain foods ferment, they produce gases and other byproducts that can lead to uncomfortable symptoms like bloating, abdominal pain, and irregular bowel movements. This dietary approach is similar to but distinct from the more widely known low FODMAP diet.

Cedars-Sinai researchers developed this approach after observing that bacterial overgrowth in the small intestine often contributes to digestive symptoms. By limiting fermentable foods, patients can reduce bacterial activity and potentially experience significant symptom relief. Unlike some elimination diets, the Low Fermentation Diet isn't meant to be followed indefinitely but rather serves as a therapeutic intervention to reset gut function.

The Science Behind Fermentation in the Gut

Fermentation is a natural process where bacteria break down carbohydrates in the absence of oxygen. While this process is normal and necessary in the large intestine, excessive fermentation in the small intestine can cause problems. The small intestine typically has fewer bacteria than the colon, but when bacterial populations increase or migrate upward from the colon (as in SIBO), they can ferment foods before proper digestion and absorption occur.

This inappropriate fermentation produces hydrogen, methane, and hydrogen sulfide gases that distend the intestine, causing pain and altered motility. Additionally, the byproducts of this fermentation can damage the intestinal lining and trigger inflammatory responses, further exacerbating symptoms. The Low Fermentation Diet aims to reduce the substrate available for these bacteria, thereby decreasing gas production and associated symptoms.

Key Components of the Low Fermentation Diet

The Low Fermentation Diet focuses on several categories of foods that are more likely to ferment in the digestive tract. Understanding these categories helps patients make informed choices about what to include and exclude from their diet during the elimination phase.

Foods to Limit or Avoid

The diet typically recommends reducing intake of highly fermentable carbohydrates, which include many of the same foods restricted on a low FODMAP diet. These include fructose (found in many fruits and honey), lactose (in dairy products), fructans (in wheat, onions, and garlic), galactans (in legumes), and polyols (sugar alcohols like sorbitol and xylitol). Additionally, the diet may limit resistant starches and certain fibers that feed bacteria.

Specific high-fermentation foods to consider limiting include wheat-based products, dairy with lactose, onions, garlic, beans, lentils, certain fruits (especially apples, pears, and watermelon), artificial sweeteners, and alcohol. Processed foods with high amounts of additives and preservatives may also promote fermentation and are generally discouraged.

Foods to Include

The Low Fermentation Diet emphasizes easily digestible proteins, certain carbohydrates, and low-fermentation vegetables. Lean proteins like chicken, turkey, fish, and eggs are generally well-tolerated. Rice, quinoa, and oats are often recommended as alternatives to wheat-based grains. Low-fermentation vegetables include carrots, cucumbers, lettuce, zucchini, and bell peppers.

Healthy fats from sources like olive oil, avocados, and nuts (in moderation) are also encouraged as they don't directly feed bacteria. Certain fruits like bananas, blueberries, oranges, and grapes are typically better tolerated than high-fructose options. The diet also allows for moderate consumption of lactose-free dairy products or plant-based alternatives.

Supplementation Strategies

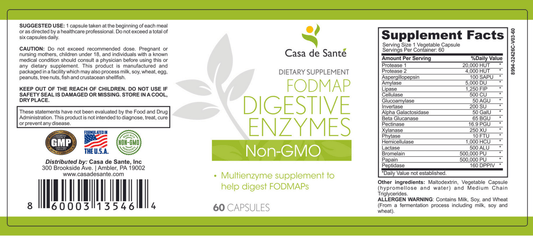

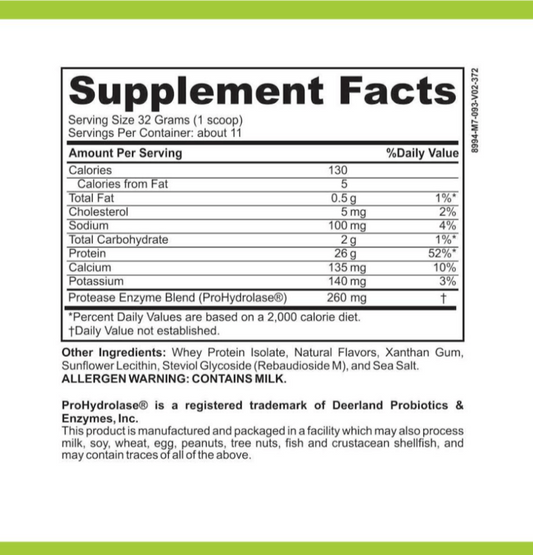

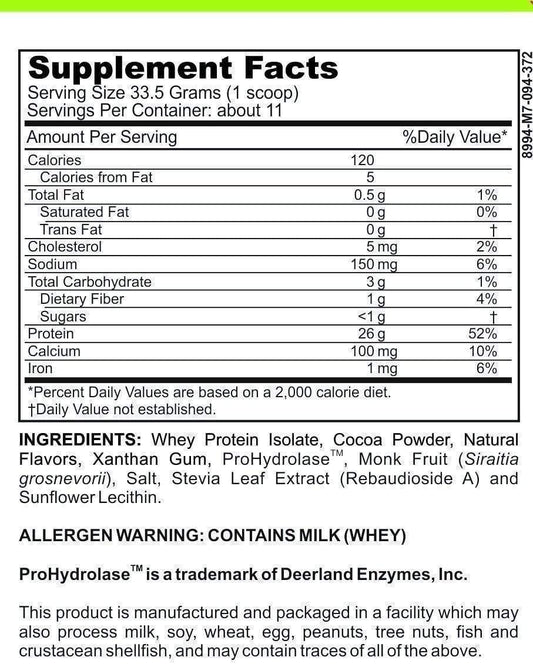

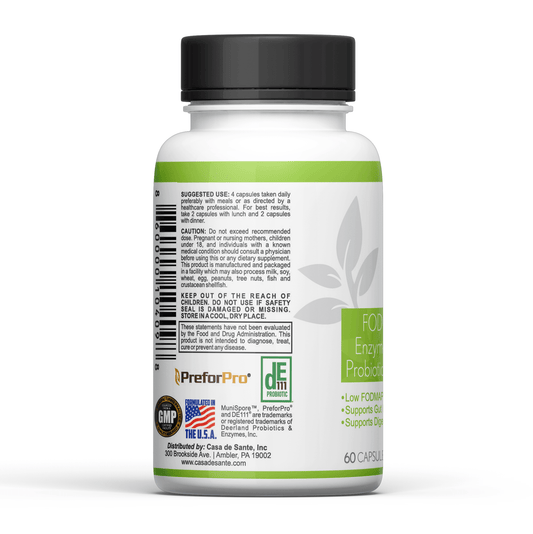

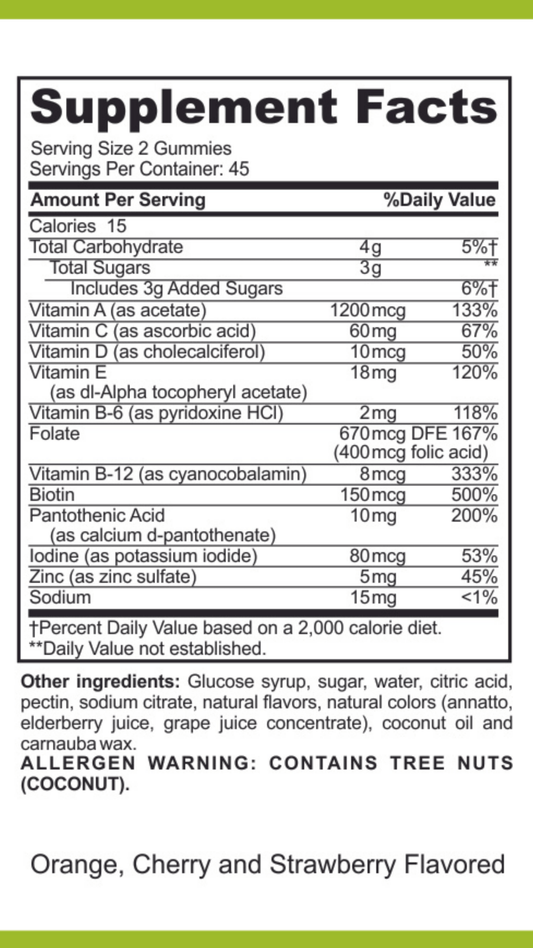

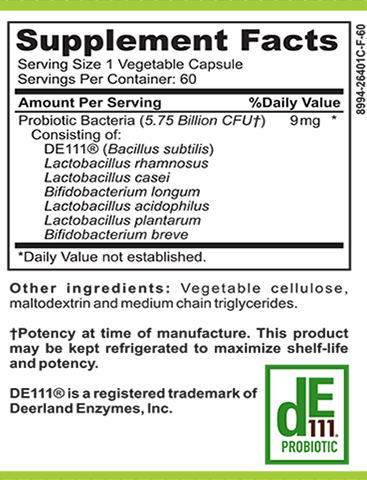

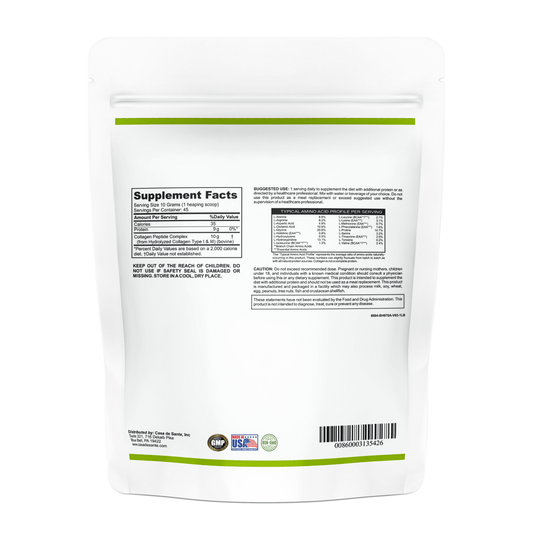

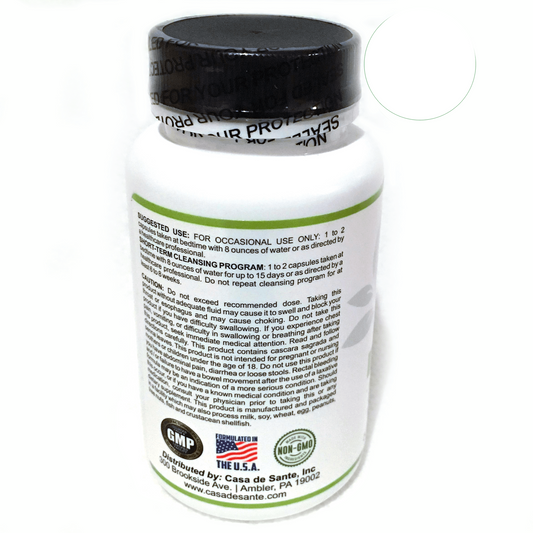

While dietary changes form the foundation of the Low Fermentation Diet, strategic supplementation can enhance its effectiveness. Digestive enzymes, in particular, can play a crucial role by helping break down foods more completely before they reach bacteria in the intestines. For those following this dietary approach, professional-grade enzyme supplements like Casa de Sante's low FODMAP certified digestive enzymes can provide significant support. These comprehensive enzyme blends are specifically designed for sensitive digestive systems and include components that target proteins, carbohydrates, and fats.

The right enzyme supplement can make a substantial difference, especially during the reintroduction phase when testing tolerance to different foods. With 18 targeted enzymes, including dual protease complexes, amylase for starch digestion, and alpha-galactosidase for FODMAP support, these supplements help optimize nutrient absorption while minimizing digestive distress. This can be particularly valuable for those who need to maintain nutritional adequacy while following a somewhat restricted diet.

Implementing the Low Fermentation Diet

Successfully implementing the Low Fermentation Diet requires a structured approach. Cedars-Sinai researchers typically recommend a phased implementation to identify trigger foods and establish a sustainable long-term eating pattern.

The Elimination Phase

The elimination phase typically lasts 2-4 weeks and involves removing high-fermentation foods from the diet. During this time, patients should keep detailed food and symptom journals to track their responses. It's important to maintain adequate nutrition during this phase, focusing on quality proteins, allowed carbohydrates, and essential fats to prevent nutritional deficiencies.

Many patients report significant symptom improvement within the first two weeks of the elimination phase. This initial response helps confirm that fermentation is indeed contributing to symptoms and provides motivation to continue with the protocol. However, it's crucial not to remain in the elimination phase indefinitely, as this could lead to unnecessary dietary restrictions and potential nutritional imbalances.

The Reintroduction Phase

After the elimination phase, foods are systematically reintroduced to identify specific triggers. This process involves adding back one food category at a time, typically over 3-4 days, while monitoring symptoms. If no symptoms occur, the food can be included in the long-term diet. If symptoms return, that food category may need to be limited or avoided.

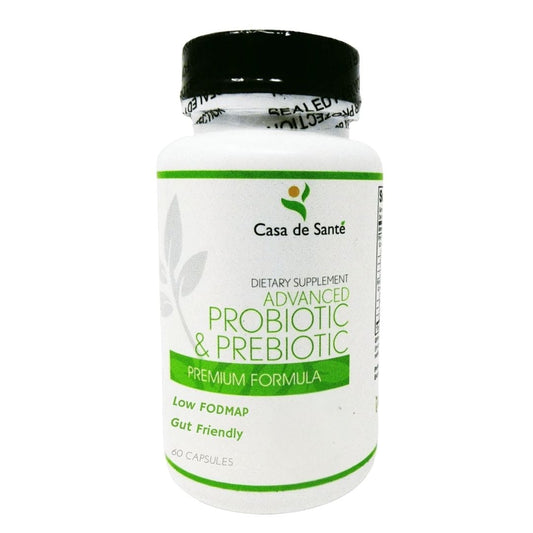

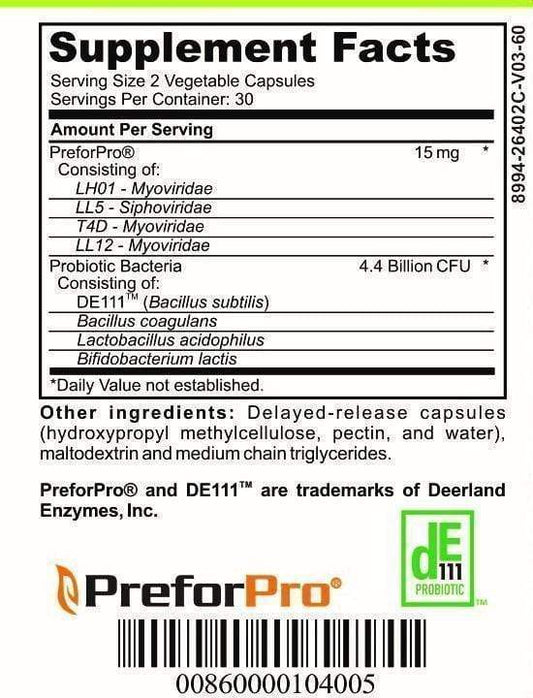

The reintroduction phase requires patience and careful observation. Some patients find that taking a high-quality digestive enzyme supplement helps them tolerate moderate amounts of certain fermentable foods. For instance, those with sensitivity to complex carbohydrates might benefit from enzymes containing amylase, alpha-galactosidase, and cellulase, which help break down starches, FODMAPs, and fiber respectively. This strategic supplementation can expand dietary options and improve quality of life.

Clinical Evidence and Research

The Low Fermentation Diet has shown promising results in clinical settings, particularly at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center where it was developed. Research indicates that patients with SIBO and IBS often experience significant symptom improvement when following this dietary approach.

Studies have demonstrated that reducing fermentable foods can decrease bacterial overgrowth in the small intestine, as measured by breath tests that detect hydrogen and methane gases. Additionally, research shows improvements in bloating, abdominal pain, and bowel regularity in many patients who adhere to the diet. The approach appears particularly effective when combined with appropriate medical treatments for underlying conditions.

Comparing to Other Therapeutic Diets

While the Low Fermentation Diet shares similarities with other therapeutic diets like the low FODMAP diet, specific carbohydrate diet (SCD), and elemental diet, it has unique features that may make it more suitable for certain patients. Unlike the low FODMAP diet, which focuses exclusively on specific carbohydrate types, the Low Fermentation Diet takes a broader approach to reducing bacterial fermentation.

The diet is generally less restrictive than the SCD and more practical than the elemental diet, making it easier to implement in everyday life. However, individual responses vary, and some patients may find better results with alternative approaches. Working with a knowledgeable healthcare provider can help determine the most appropriate dietary strategy based on specific symptoms and conditions.

Practical Tips for Success

Successfully following the Low Fermentation Diet requires planning, preparation, and patience. These practical tips can help make the process more manageable and effective.

Meal Planning and Preparation

Advance meal planning is essential when following the Low Fermentation Diet. Creating weekly meal plans, preparing shopping lists, and batch cooking compliant meals can prevent last-minute food choices that might trigger symptoms. Simple, whole-food meals often work best, as they contain fewer potentially problematic ingredients.

Many patients find that investing in quality storage containers, a good blender, and perhaps a food processor makes preparation easier. Additionally, keeping a supply of compliant snacks on hand can help manage hunger between meals without compromising the diet. When digestive symptoms are particularly challenging, supporting your body with professional-grade enzyme supplements can make a significant difference in comfort and nutrient absorption.

Navigating Social Situations

Eating out and social gatherings can present challenges when following a specialized diet. When dining out, research restaurant menus in advance and don't hesitate to ask about ingredients or request simple modifications. For social events, consider eating a small meal beforehand and focusing on clearly identifiable low-fermentation options at the gathering.

Being open with friends and family about dietary needs can also help create a supportive environment. Many find that carrying digestive enzyme supplements provides an extra layer of security when eating in situations where food choices might be limited or uncertain. This approach allows for greater flexibility while still managing symptoms effectively.

The Low Fermentation Diet represents an important therapeutic option for those struggling with digestive symptoms related to bacterial overgrowth and fermentation. By understanding and implementing this approach under appropriate medical guidance, many patients can experience significant improvements in their digestive health and quality of life. As research continues to evolve, this dietary strategy will likely become an increasingly valuable tool in the management of functional gastrointestinal disorders.