Intestinal Peristalsis: Sibo Explained

Intestinal Peristalsis: Sibo Explained

Intestinal peristalsis is a crucial biological process that aids in the digestion and absorption of nutrients in the human body. It refers to the rhythmic, wave-like contractions and relaxations of the muscles in the gastrointestinal tract, which propel food and waste materials through the digestive system. In the context of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO), understanding the role and function of intestinal peristalsis is critical, as any disruption in this process can contribute to the onset and progression of SIBO.

SIBO is a medical condition characterized by an excessive amount of bacteria in the small intestine. This bacterial overgrowth can lead to a variety of symptoms, including bloating, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and malnutrition. The relationship between intestinal peristalsis and SIBO is complex and multifaceted, involving factors such as gut motility, bacterial flora, and the integrity of the intestinal barrier.

Understanding Intestinal Peristalsis

Intestinal peristalsis is a fundamental physiological process that ensures the efficient movement of food and waste products through the digestive tract. It involves a series of coordinated muscular contractions and relaxations that push the contents of the gut forward. This process is controlled by the enteric nervous system, a complex network of neurons embedded in the walls of the gastrointestinal tract.

The process of peristalsis begins in the esophagus when food is swallowed. The wave-like contractions continue down the stomach and through the small and large intestines, eventually leading to the expulsion of waste materials through the rectum. The rate and intensity of these contractions can be influenced by various factors, including the type and quantity of food consumed, the presence of certain hormones, and the overall health of the digestive system.

The Role of the Enteric Nervous System

The enteric nervous system (ENS) plays a pivotal role in regulating the process of intestinal peristalsis. Often referred to as the "second brain," the ENS consists of over 100 million neurons that independently control the function of the gastrointestinal tract. These neurons coordinate the contractions of the smooth muscle layers in the gut wall, thereby regulating the speed and pattern of peristalsis.

The ENS communicates with the central nervous system (CNS) through the vagus nerve, allowing the brain to influence gut motility. For instance, stress and anxiety can slow down peristalsis, leading to constipation, while excitement can speed it up, resulting in diarrhea. Understanding the intricate relationship between the ENS and CNS is crucial in managing conditions like SIBO, where gut motility is often impaired.

Factors Influencing Intestinal Peristalsis

Several factors can influence the rate and intensity of intestinal peristalsis. Dietary factors, such as the consumption of high-fiber foods, can stimulate peristalsis by adding bulk to the stool and triggering the stretch receptors in the gut wall. On the other hand, low-fiber diets can slow down peristalsis, leading to constipation.

Other factors that can affect peristalsis include hydration status, physical activity, and certain medications. Dehydration can slow down peristalsis, as the body absorbs more water from the gut to compensate for the fluid loss, resulting in harder and less frequent stools. Regular physical activity can stimulate peristalsis by increasing the metabolic rate and promoting the movement of food through the digestive tract. Certain medications, such as opioids and anticholinergics, can also interfere with peristalsis by affecting the nerve signals in the gut.

Intestinal Peristalsis and SIBO

Impaired intestinal peristalsis is a key factor in the development of SIBO. When the normal peristaltic waves are disrupted, it can lead to stagnation of food and waste materials in the small intestine. This creates a conducive environment for the overgrowth of bacteria, leading to the symptoms associated with SIBO.

Several conditions can lead to impaired peristalsis and contribute to the development of SIBO. These include motility disorders, such as gastroparesis and chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction, neurological disorders, such as Parkinson's disease and multiple sclerosis, and systemic conditions, such as diabetes and scleroderma. In these conditions, the normal coordination of the muscular contractions in the gut is disrupted, leading to abnormal peristaltic patterns.

Motility Disorders and SIBO

Motility disorders are conditions that affect the ability of the gastrointestinal tract to contract and relax in a coordinated manner. In conditions like gastroparesis and chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction, the normal peristaltic waves are disrupted, leading to delayed gastric emptying and stagnation of food in the gut. This can result in bacterial overgrowth in the small intestine, leading to the symptoms of SIBO.

Managing motility disorders often involves addressing the underlying cause, improving dietary habits, and using medications to enhance gut motility. Prokinetic agents, such as metoclopramide and erythromycin, are commonly used to stimulate peristalsis and improve gastric emptying. However, these medications should be used with caution, as they can have side effects and may not be suitable for all patients.

Neurological Disorders and SIBO

Neurological disorders, such as Parkinson's disease and multiple sclerosis, can also affect intestinal peristalsis and contribute to the development of SIBO. These conditions can damage the nerves that control gut motility, leading to dysregulated peristalsis and bacterial overgrowth.

Management of SIBO in patients with neurological disorders involves a multidisciplinary approach, including dietary modifications, prokinetic medications, and antibiotics to reduce bacterial overgrowth. In some cases, physical therapy and biofeedback techniques may also be used to improve gut motility and enhance quality of life.

Diagnosing and Treating SIBO

Diagnosing SIBO can be challenging, as the symptoms often overlap with other gastrointestinal disorders. The gold standard for diagnosing SIBO is the small intestine aspirate and culture, where a sample of fluid is taken from the small intestine and cultured to detect bacterial overgrowth. However, this procedure is invasive and not routinely performed. Instead, breath tests are commonly used to diagnose SIBO. These tests measure the levels of hydrogen and methane in the breath, which are produced by bacterial fermentation in the gut.

Treatment of SIBO typically involves a combination of antibiotics to reduce bacterial overgrowth, prokinetic agents to improve gut motility, and dietary modifications to manage symptoms. The choice of antibiotic depends on the type of bacteria involved and the patient's individual characteristics. Rifaximin is commonly used to treat SIBO due to its broad-spectrum activity and minimal systemic absorption.

Role of Diet in Managing SIBO

Diet plays a crucial role in managing SIBO. Certain foods can exacerbate symptoms by feeding the bacteria in the gut and promoting their growth. These include high-sugar foods, refined carbohydrates, and certain types of fiber that are fermented by gut bacteria. The low FODMAP diet, which restricts the intake of these fermentable carbohydrates, has been shown to be effective in managing SIBO symptoms.

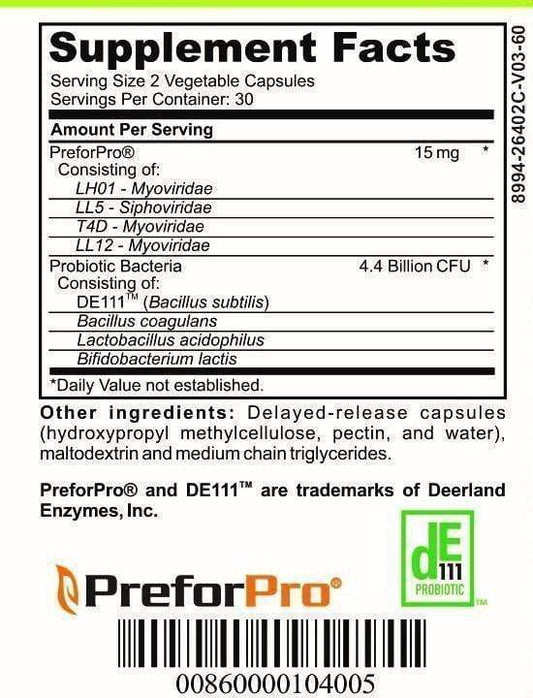

Probiotics and prebiotics may also be beneficial in managing SIBO. Probiotics are live bacteria that can help restore the balance of gut flora, while prebiotics are non-digestible carbohydrates that feed the beneficial bacteria in the gut. However, the use of these supplements should be individualized, as they may not be suitable for all patients with SIBO.

Future Directions in SIBO Research

Despite significant advances in our understanding of SIBO, many questions remain unanswered. Future research is needed to better understand the complex interplay between intestinal peristalsis, gut flora, and the immune system in the pathogenesis of SIBO. This could lead to the development of novel diagnostic tools and therapeutic strategies for this condition.

There is also a need for more clinical trials to evaluate the efficacy and safety of various treatment strategies for SIBO. This includes the use of novel antibiotics, prokinetic agents, dietary interventions, and probiotic and prebiotic supplements. By advancing our knowledge in these areas, we can improve the management of SIBO and enhance the quality of life for patients affected by this condition.