How FODMAPs Cause Constipation: Understanding the Digestive Connection

How FODMAPs Cause Constipation: Understanding the Digestive Connection

Constipation affects millions of people worldwide, causing discomfort, bloating, and frustration. While many factors contribute to constipation, diet plays a crucial role in digestive health. In recent years, researchers have identified FODMAPs as potential culprits behind constipation for many individuals. These fermentable carbohydrates, found in various foods, can significantly impact gut function and bowel movements. Understanding how FODMAPs affect your digestive system might be the key to finding relief from chronic constipation.

What Are FODMAPs?

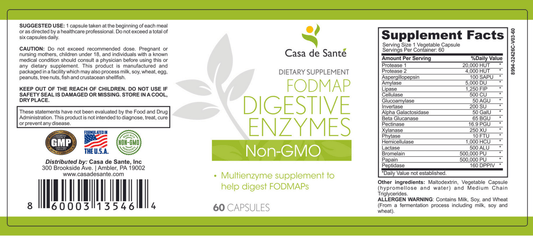

FODMAP is an acronym that stands for Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides, And Polyols. These are types of short-chain carbohydrates and sugar alcohols that are poorly absorbed in the small intestine. Instead of being properly digested, these compounds pass through to the large intestine where gut bacteria ferment them, potentially causing digestive symptoms in sensitive individuals.

Breaking Down the FODMAP Categories

Understanding each component of FODMAPs helps identify problematic foods in your diet. Oligosaccharides include fructans and galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS), found in wheat, rye, onions, garlic, and legumes. Disaccharides primarily refer to lactose, present in dairy products like milk, soft cheese, and yogurt. Monosaccharides mainly involve excess fructose, found in honey, apples, and high-fructose corn syrup. Polyols are sugar alcohols such as sorbitol and mannitol, present in some fruits and vegetables as well as artificial sweeteners.

Each of these FODMAP categories affects the digestive system differently, but they share a common trait: they can draw water into the intestine and undergo bacterial fermentation, leading to gas production. For some people, this combination creates the perfect storm for constipation and other digestive issues.

The sensitivity to FODMAPs varies significantly from person to person, with those suffering from Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) typically experiencing the most severe reactions. Research from Monash University in Australia, where the low-FODMAP diet was developed, suggests that up to 75% of IBS patients experience relief when following a properly structured low-FODMAP eating plan. The degree of sensitivity can also fluctuate within individuals based on factors like stress levels, hormonal changes, and overall gut health, making FODMAP tolerance a dynamic rather than static condition.

It's important to note that FODMAPs themselves aren't inherently unhealthy—in fact, many high-FODMAP foods are nutritionally valuable and promote beneficial gut bacteria. The fermentation process that causes discomfort in sensitive individuals actually produces short-chain fatty acids that support colon health in those who tolerate FODMAPs well. This paradox highlights why a low-FODMAP diet isn't recommended as a permanent lifestyle for most people, but rather as a diagnostic tool and temporary intervention to identify specific triggers before reintroducing tolerated foods systematically.

The Paradox: How FODMAPs Cause Constipation

It might seem counterintuitive that FODMAPs could cause constipation, especially since they're often associated with diarrhea in IBS patients. However, digestive responses to FODMAPs vary widely among individuals, and constipation is indeed a common reaction for many people.

The Water-Drawing Effect

FODMAPs are osmotically active, meaning they draw water into the intestinal lumen. In some individuals, this extra water is efficiently absorbed in the colon, leaving stool dry and difficult to pass. This is particularly true when transit time through the intestines is slow, giving the body more time to absorb water from the stool, resulting in constipation.

Bacterial Fermentation and Gas Production

When FODMAPs reach the large intestine, gut bacteria ferment them, producing gases like hydrogen, methane, and carbon dioxide. Research has shown that individuals who produce more methane gas tend to have slower gut transit times. Methane gas can actually slow down intestinal movement by affecting the muscles that control peristalsis (the wave-like contractions that move food through the digestive tract). This slowing effect can lead to constipation as waste moves too slowly through the colon, allowing excessive water absorption.

Gut Microbiome Imbalance

High FODMAP consumption can alter the gut microbiome composition in sensitive individuals. Some studies suggest that certain bacterial populations that thrive on FODMAPs may contribute to constipation by affecting gut motility and inflammation. This dysbiosis (imbalance of gut bacteria) can disrupt the normal functioning of the digestive system, potentially leading to chronic constipation.

Common High-FODMAP Foods That May Contribute to Constipation

Identifying high-FODMAP foods in your diet is the first step toward understanding if they're contributing to your constipation. While individual tolerance varies, certain foods are particularly high in FODMAPs and commonly associated with digestive symptoms.

Fruits and Vegetables

Several fruits and vegetables contain high levels of FODMAPs. Apples, pears, watermelon, and cherries are high in excess fructose or polyols. Vegetables like onions, garlic, mushrooms, cauliflower, and artichokes contain significant amounts of oligosaccharides. While these foods are nutritious, they may contribute to constipation in sensitive individuals due to their FODMAP content.

Interestingly, some fruits like unripe bananas contain resistant starch, which can act as a prebiotic and potentially slow gut transit in some people. As bananas ripen, this starch converts to more digestible sugars, making ripe bananas a better choice for those prone to constipation.

Grains and Legumes

Wheat, rye, and barley contain fructans, a type of oligosaccharide that can be particularly problematic for some people. These grains are ubiquitous in Western diets, appearing in bread, pasta, cereals, and baked goods. Legumes such as chickpeas, lentils, and beans are high in galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS), another FODMAP category that can contribute to constipation in sensitive individuals.

Dairy Products

Lactose-containing dairy products like milk, ice cream, and soft cheeses can be problematic for those with lactose intolerance. While lactose is often associated with diarrhea, some individuals experience constipation instead, particularly when dairy consumption leads to methane-dominant fermentation in the gut. Hard, aged cheeses and lactose-free dairy products are typically lower in FODMAPs and may be better tolerated.

Identifying Your FODMAP Triggers

Not everyone reacts to FODMAPs in the same way. Some people may be sensitive to certain categories while tolerating others perfectly well. Identifying your specific triggers is crucial for managing constipation effectively.

The Elimination and Reintroduction Process

The gold standard for identifying FODMAP sensitivities is a structured elimination and reintroduction process, ideally guided by a registered dietitian. This approach involves removing all high-FODMAP foods from your diet for 2-6 weeks, then systematically reintroducing them one category at a time. By carefully tracking symptoms during reintroduction, you can identify which specific FODMAPs trigger your constipation.

During the elimination phase, it's important to follow a nutritionally balanced low-FODMAP diet rather than simply removing foods without replacement. This helps ensure you're getting adequate fiber and nutrients while testing your FODMAP tolerance. Many people find that they only react to specific FODMAP groups, allowing them to enjoy a more varied diet while avoiding just their trigger foods.

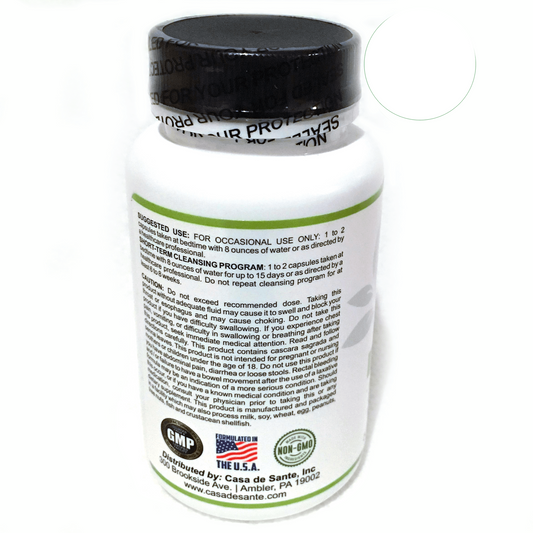

Managing FODMAP-Related Constipation

Once you've identified your FODMAP triggers, several strategies can help manage constipation while maintaining a nutritious, enjoyable diet.

Dietary Modifications

Rather than eliminating all FODMAPs permanently, most experts recommend a personalized approach based on your specific triggers and tolerance levels. This might mean reducing rather than eliminating certain foods, or consuming them in smaller portions that stay below your personal threshold. For example, you might tolerate half an apple but experience symptoms after eating a whole one.

Focusing on low-FODMAP alternatives can help maintain dietary variety. For instance, if wheat causes problems, alternatives like sourdough bread (which has lower FODMAP content due to fermentation), rice, quinoa, or gluten-free oats might be better tolerated. Similarly, replacing onions and garlic with garlic-infused oil provides flavor without the FODMAPs, as the problematic compounds aren't oil-soluble.

Balancing Fiber Intake

Fiber is crucial for healthy bowel function, but the type of fiber matters when managing FODMAP-related constipation. Soluble fiber, found in low-FODMAP foods like oats, chia seeds, and oranges, can help soften stool and promote regularity. Insoluble fiber, found in foods like brown rice, carrots, and zucchini, adds bulk to stool and helps it move through the digestive tract more efficiently.

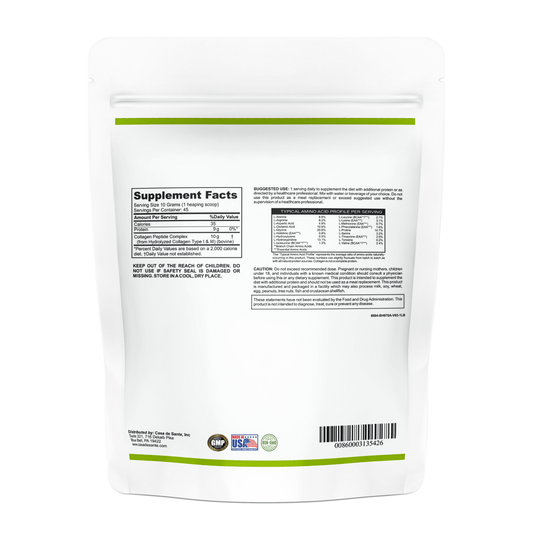

Gradually increasing fiber intake while ensuring adequate hydration is key. Adding too much fiber too quickly can worsen symptoms, so a measured approach is recommended. Some people find that a supplement like psyllium husk, which contains both soluble and insoluble fiber, helps manage constipation without triggering FODMAP-related symptoms.

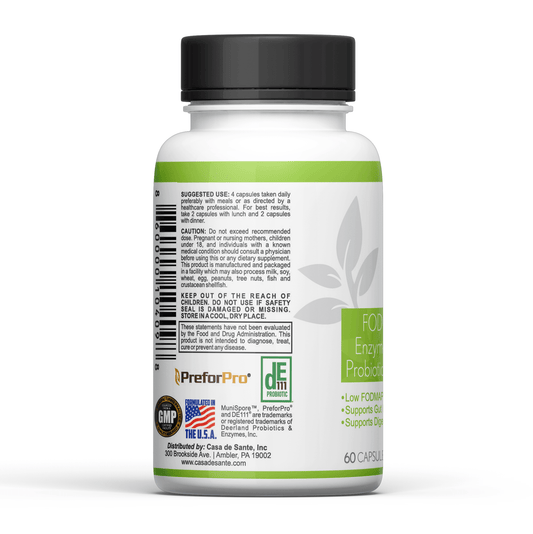

Supporting Gut Health

Beyond managing FODMAPs, supporting overall gut health can help alleviate constipation. Regular physical activity stimulates intestinal contractions, helping move stool through the colon. Stress management is also important, as the gut-brain connection means psychological stress can worsen digestive symptoms.

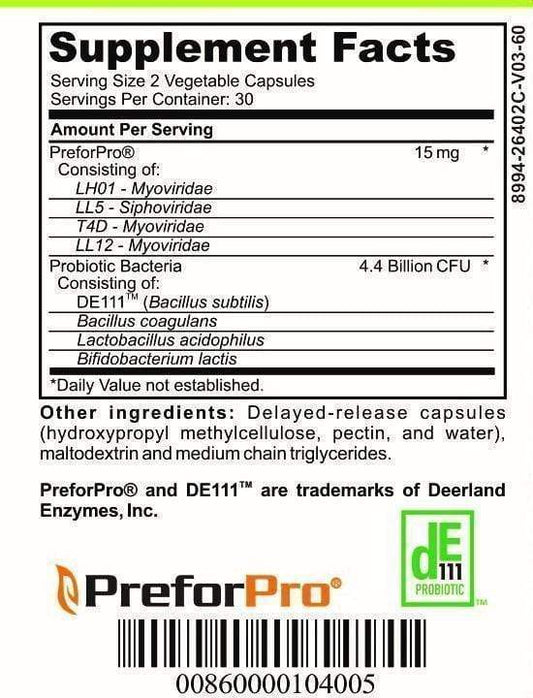

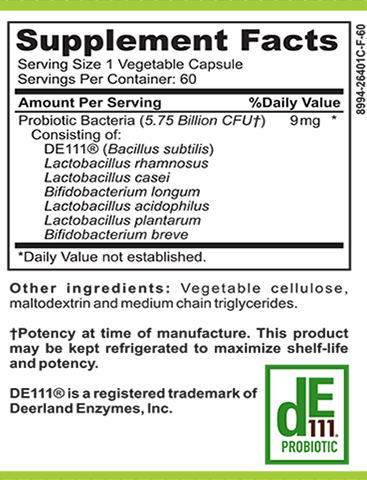

Probiotic supplements or fermented foods may help some individuals by supporting a healthy gut microbiome. However, it's important to choose options that don't contain high levels of FODMAPs. For example, traditional yogurt contains lactose, but lactose-free or coconut yogurt with live cultures might be better tolerated while still providing beneficial bacteria.

When to Seek Professional Help

While dietary modifications can significantly improve FODMAP-related constipation, persistent symptoms warrant professional attention. Chronic constipation can sometimes indicate underlying medical conditions that require specific treatment.

A gastroenterologist can rule out conditions like hypothyroidism, medication side effects, or structural issues in the digestive tract. They may recommend diagnostic tests like blood work, colonoscopy, or transit studies to understand the root cause of constipation. Working with a registered dietitian who specializes in digestive health can also provide personalized guidance on managing FODMAPs while maintaining nutritional adequacy.

Remember that while FODMAPs can contribute to constipation, they're just one piece of the digestive puzzle. A comprehensive approach that considers all aspects of digestive health typically yields the best results for long-term symptom management and improved quality of life.