Can Inulin Make IBS Worse? Understanding the Connection

Can Inulin Make IBS Worse? Understanding the Connection

Living with Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) means navigating a complex relationship with food. Just when you think you've figured out your triggers, a new ingredient or supplement enters the conversation. Inulin, a popular prebiotic fiber found in many foods and supplements, has gained attention for its gut health benefits. But for those with IBS, this seemingly beneficial fiber might actually be causing more harm than good.

What Exactly Is Inulin?

Inulin is a type of soluble fiber that belongs to a class of compounds called fructans. It's naturally present in many plants, serving as their energy storage. Unlike other carbohydrates, inulin isn't digested in the upper gastrointestinal tract; instead, it passes through to the colon where it becomes food for beneficial gut bacteria.

Common food sources of inulin include chicory root, Jerusalem artichokes, garlic, onions, leeks, and bananas. It's also frequently added to processed foods as a fiber supplement or fat substitute, appearing on labels as chicory root extract, oligofructose, or fructooligosaccharides (FOS).

The Prebiotic Properties of Inulin

Inulin has earned its reputation as a prebiotic – a substance that promotes the growth of beneficial bacteria in the gut. When inulin reaches your colon, bacteria ferment it, producing short-chain fatty acids like butyrate that nourish colon cells and provide various health benefits. This fermentation process is what makes inulin valuable for general gut health, potentially supporting immune function and even helping with mineral absorption.

For many people, incorporating prebiotics like inulin can lead to a healthier gut microbiome and improved digestive function. However, this same fermentation process that benefits some can spell trouble for those with IBS.

How Inulin Affects IBS Symptoms

For individuals with IBS, the relationship with inulin is complicated. The very properties that make inulin beneficial for gut health in general can exacerbate symptoms in those with sensitive digestive systems. Understanding this connection requires looking at how inulin interacts with an IBS-affected gut.

The Fermentation Problem

When inulin ferments in the colon, it produces gases including hydrogen, carbon dioxide, and in some people, methane. For those with IBS, this gas production can lead to bloating, abdominal pain, and distension – hallmark symptoms of the condition. The rapid fermentation can also alter gut motility, potentially worsening diarrhea in IBS-D (diarrhea-predominant IBS) or constipation in IBS-C (constipation-predominant IBS).

Dr. Megan Rossi, known as The Gut Health Doctor, explains: "While prebiotics like inulin feed beneficial bacteria, the fermentation process can be problematic for those with visceral hypersensitivity, which is common in IBS. These individuals may experience pain and discomfort at gas levels that wouldn't bother others."

FODMAPs and IBS

Inulin is classified as a FODMAP (Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides, and Polyols) – specifically, it falls under the oligosaccharide category. FODMAPs are notorious for triggering IBS symptoms, and many IBS management strategies involve reducing FODMAP intake.

The low-FODMAP diet, developed by researchers at Monash University, has shown effectiveness in managing IBS symptoms for approximately 75% of patients. This diet specifically restricts foods high in inulin and other fructans, highlighting their potential to worsen IBS symptoms.

Individual Variation in Response

Not everyone with IBS reacts the same way to inulin. Some may experience severe symptoms even with small amounts, while others might tolerate moderate quantities without issue. This variation depends on factors including gut microbiome composition, intestinal transit time, and the specific subtype of IBS.

Research suggests that those with IBS-D might be particularly sensitive to inulin's effects, as the increased gas production can stimulate contractions in the colon, potentially accelerating transit time and worsening diarrhea symptoms.

Research on Inulin and IBS

Scientific studies examining the relationship between inulin and IBS have produced mixed results, reflecting the complex and individualized nature of the condition.

Evidence Supporting Caution

A 2010 study published in the American Journal of Gastroenterology found that fructans (including inulin) significantly increased IBS symptoms compared to a placebo. Participants reported more severe bloating, gas, and abdominal pain when consuming fructans, supporting the theory that these compounds can trigger IBS flares.

More recently, a 2018 double-blind crossover study in Gastroenterology demonstrated that fructans were more likely than gluten to induce symptoms in patients with self-reported non-celiac gluten sensitivity – many of whom meet criteria for IBS. This finding suggests that for some people diagnosed with IBS, fructans like inulin might be the real culprit behind their digestive distress.

Potential Benefits for Some IBS Patients

Interestingly, not all research paints inulin as problematic for IBS. Some studies suggest that very gradual introduction of small amounts of inulin might actually help certain IBS patients by slowly modifying their gut microbiome in a positive direction. A 2016 study in Neurogastroenterology & Motility found that low doses of oligofructose (a type of inulin) improved stool consistency in IBS-C patients without significantly increasing gas-related symptoms.

The key appears to be dosage and adaptation. While large amounts of inulin can overwhelm a sensitive digestive system, minimal doses introduced gradually might allow the gut to adapt and potentially benefit from the prebiotic effects.

Identifying If Inulin Is Triggering Your IBS

If you suspect inulin might be worsening your IBS symptoms, there are several approaches to determine whether it's a trigger for you personally.

Food and Symptom Journaling

One of the most effective methods is keeping a detailed food and symptom journal. Record everything you eat and drink, along with any digestive symptoms you experience. Look for patterns between consuming inulin-rich foods or supplements and symptom flares. Common high-inulin foods to watch for include garlic, onions, wheat, chicory root, Jerusalem artichokes, and processed foods with added inulin or chicory root extract.

Pay attention to timing as well – symptoms from inulin consumption typically appear within a few hours but can sometimes be delayed, making identification challenging without systematic tracking.

Elimination and Challenge

A more structured approach involves temporarily eliminating all significant sources of inulin from your diet for 2-4 weeks, then systematically reintroducing them while monitoring symptoms. This method, similar to the reintroduction phase of the low-FODMAP diet, can help pinpoint whether inulin specifically triggers your symptoms and at what threshold.

Registered dietitian Kate Scarlata recommends: "Start with very small amounts when reintroducing potential trigger foods. For inulin-containing foods, begin with just a teaspoon of onion in a dish, for example, rather than a whole onion. This helps identify your personal tolerance threshold."

Managing IBS When Inulin Is a Trigger

If you've determined that inulin aggravates your IBS symptoms, several strategies can help you manage this trigger while maintaining overall gut health.

Dietary Modifications

The most straightforward approach is reducing your intake of high-inulin foods and products. This doesn't necessarily mean eliminating all sources completely – many people with IBS can tolerate small amounts of trigger foods without significant symptoms. Learning your personal threshold is key.

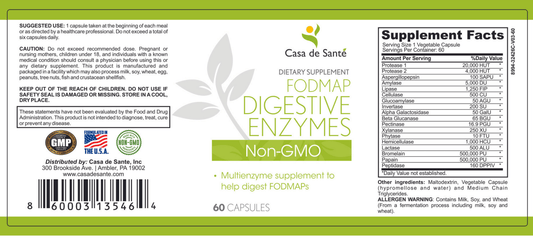

When reading food labels, look for terms like inulin, chicory root extract, Jerusalem artichoke flour, oligofructose, and fructooligosaccharides. These ingredients are increasingly common in "high-fiber" or "gut-friendly" products, which ironically may be particularly problematic for those with IBS.

Alternative Prebiotic Sources

If you're concerned about missing the prebiotic benefits of inulin, consider alternative prebiotic sources that might be better tolerated. Small amounts of ripe bananas, blueberries, kiwi fruit, or oats provide prebiotic effects with potentially less fermentation and gas production.

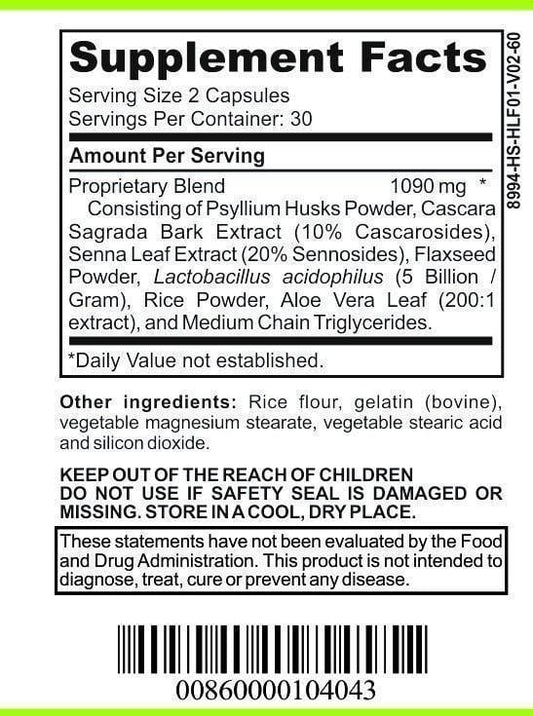

Some people with IBS also find they can tolerate resistant starch, another type of prebiotic found in cooled potatoes, rice, and green bananas. These foods feed beneficial bacteria but through different mechanisms than inulin, potentially causing less gas and bloating.

Working with Healthcare Providers

Managing IBS effectively often requires professional guidance. A gastroenterologist can help rule out other conditions and provide medical management options, while a registered dietitian specializing in digestive disorders can develop a personalized nutrition plan that avoids triggers while ensuring nutritional adequacy.

Dietitians can also guide you through structured approaches like the low-FODMAP diet, which restricts inulin along with other fermentable carbohydrates, then systematically reintroduces them to determine specific triggers and tolerance thresholds.

The Future of Inulin and IBS Management

Research into IBS and its dietary management continues to evolve. Recent developments suggest that the relationship between inulin and IBS might be more nuanced than initially thought.

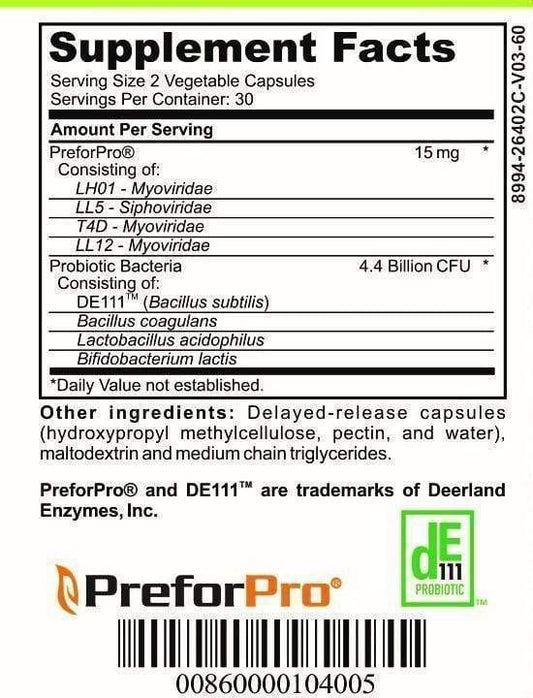

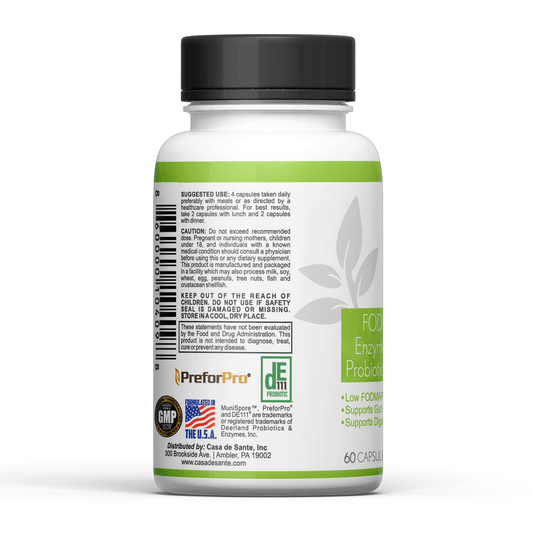

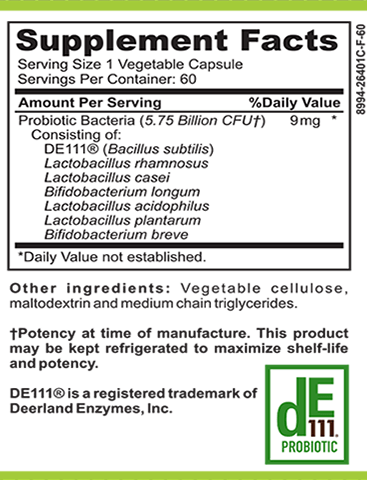

Emerging studies are exploring whether certain strains of probiotics might help IBS patients better tolerate prebiotics like inulin. Other research is investigating whether the processing method of inulin affects its fermentation rate and symptom-triggering potential. Some modified forms of inulin with longer chains (higher degree of polymerization) might ferment more slowly, potentially reducing gas production and associated symptoms.

As our understanding of the gut microbiome grows, we may develop more personalized approaches to prebiotics in IBS management, potentially allowing more people with IBS to benefit from inulin's positive effects without suffering its downsides.

Conclusion

The question "Can inulin make IBS worse?" doesn't have a simple yes or no answer. For many people with IBS, particularly those sensitive to FODMAPs, inulin can indeed trigger or worsen symptoms through its fermentation in the colon. However, individual responses vary greatly, and some may tolerate small amounts or even benefit from gradual introduction.

If you have IBS and are concerned about inulin, the best approach is methodical: identify whether it's a personal trigger, determine your tolerance threshold if any, and work with healthcare providers to develop a management strategy that addresses your symptoms while supporting overall gut health. Remember that dietary management of IBS is highly individualized – what triggers one person's symptoms may be well-tolerated by another.

By understanding the connection between inulin and IBS, you can make more informed choices about your diet and supplements, potentially reducing symptoms and improving your quality of life with this challenging condition.