Why Do Some Foods Trigger Your Gag Reflex? Understanding Food Aversions

Why Do Some Foods Trigger Your Gag Reflex? Understanding Food Aversions

We've all been there – sitting at a dinner table, confronted with a plate of food that makes our throat tighten and our stomach churn. Maybe it's the slippery texture of oysters, the pungent aroma of blue cheese, or the bitter taste of Brussels sprouts. food aversions are surprisingly common, yet deeply personal experiences that can range from mild dislike to intense physical reactions. But what exactly happens in our bodies and brains when certain foods trigger our gag reflex? And why do some people recoil at foods others consider delicacies?

The Science Behind Your Gag Reflex

The gag reflex, technically known as the pharyngeal reflex, is your body's natural defense mechanism against choking and ingesting potentially harmful substances. When triggered, it causes the muscles at the back of your throat to contract, creating that unmistakable sensation of wanting to retch or vomit. This protective response is controlled by your brain stem and involves cranial nerves that monitor what enters your throat.

While primarily designed to protect us from physical dangers, the gag reflex can become hypersensitive and respond to certain tastes, textures, smells, or even the mere thought of particular foods. This heightened sensitivity often forms the physiological basis of food aversions that can last a lifetime.

How Taste and Texture Trigger Aversions

Our sensory perception of food is remarkably complex. When we eat, we're not just tasting with our taste buds – we're experiencing a symphony of sensory input including texture, temperature, smell, and even the sound food makes when we chew it. For many people with strong food aversions, texture is often the primary culprit.

Slimy, gelatinous, or mushy textures frequently top the list of texture-based aversions. Foods like oysters, okra, or overripe bananas can trigger the gag reflex in sensitive individuals because these textures may subconsciously signal potential spoilage or contamination to our primitive brain. Similarly, extremely bitter tastes, which historically might indicate poison in nature, can provoke strong aversive reactions.

The Evolutionary Perspective

From an evolutionary standpoint, food aversions make perfect sense. Our ancestors who developed quick and strong negative reactions to potentially harmful foods were more likely to survive. This explains why bitter tastes, which often indicate toxicity in nature, commonly trigger aversions. It's also why many food aversions develop after a single negative experience – a phenomenon called conditioned taste aversion.

This rapid-learning mechanism helped our ancestors avoid repeated exposure to foods that made them sick. Even today, if you get food poisoning after eating a particular dish, you might find yourself unable to stomach that same food for years afterward, even when you consciously know the food itself wasn't the problem.

Psychological Factors in Food Aversions

While physiological reactions form the foundation of many food aversions, psychology plays an equally important role. Our experiences, memories, and even cultural background significantly influence which foods we find repulsive and which we crave.

Childhood Experiences and Food Memory

Many food aversions take root in childhood. Children are naturally neophobic (afraid of new things), especially when it comes to food – an evolutionary adaptation that prevented curious youngsters from eating unknown, potentially dangerous substances. This explains why many children go through picky eating phases, often rejecting foods based on appearance alone.

The way food is presented or forced during childhood can create lasting aversions. Many adults who were forced to "clean their plates" or eat foods they disliked as children carry those aversions into adulthood. These negative associations become deeply embedded in our food memory, triggering the gag reflex even decades later.

Cultural Influences on Food Acceptance

What's considered delicious in one culture might trigger disgust in another. Consider how some cultures relish fermented foods with strong odors, while others find them revolting. These differences highlight how our food preferences are shaped by cultural exposure and normalization.

Cultural conditioning begins early – children learn what foods are "normal" and "good" based on what's served at home and what they see others enjoying. This explains why foods like durian, hákarl (fermented shark), or even peanut butter can provoke such different reactions depending on where you were raised.

Common Food Aversions and Their Triggers

While food aversions are highly individual, certain foods consistently top the list of commonly rejected items. Understanding what makes these foods particularly triggering can help us better comprehend our own aversions.

Texture-Based Aversions

Texture is perhaps the most common trigger for food aversions and gagging responses. Foods with contrasting textures or those that change in the mouth often provoke strong reactions. Common offenders include:

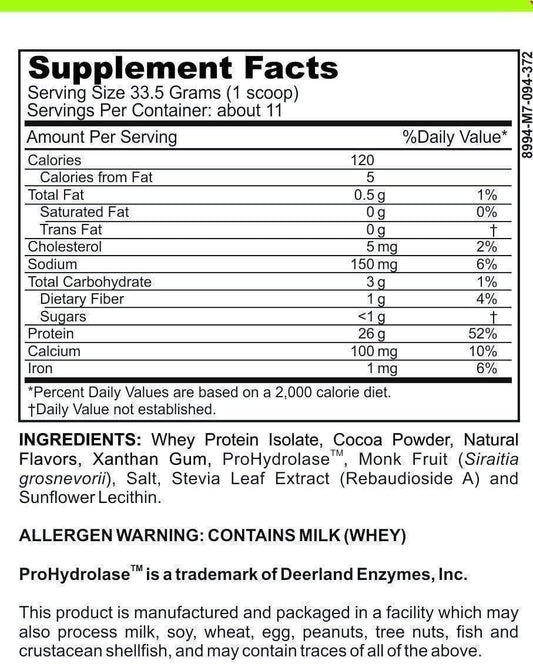

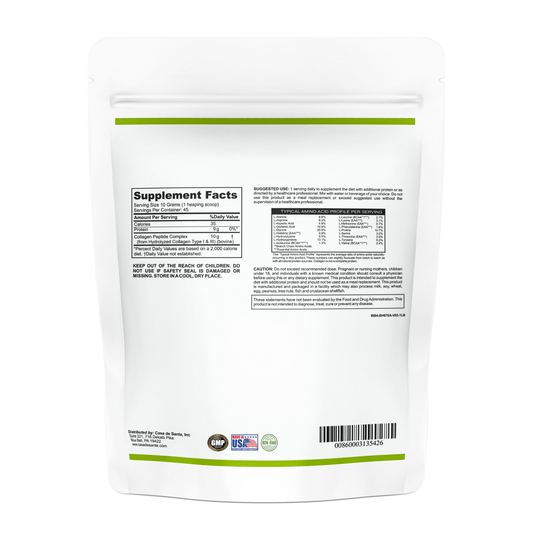

Oysters and other shellfish, with their slippery, gelatinous consistency; mushrooms, which some describe as "spongy" or "rubbery"; and foods with unexpected textures like tapioca pudding with its small, slippery pearls. For people with texture sensitivities, finding alternatives with similar nutritional profiles but different textures can be helpful. For instance, those who struggle with protein sources due to texture issues might benefit from incorporating easily digestible options like Casa de Sante's low FODMAP certified protein powders, which provide essential nutrients without triggering texture-based aversions.

Smell-Triggered Aversions

Our sense of smell is intimately connected with our taste perception and can trigger the gag reflex before food even reaches our mouths. Foods with strong, pungent aromas frequently cause aversive reactions. Notorious examples include durian (often banned in public places due to its smell), certain cheeses like Limburger or blue cheese, and fermented foods like kimchi or surströmming.

For those with smell-based aversions, preparation techniques that minimize odors can help. Cooking outdoors, using lids while cooking, or masking challenging scents with complementary aromas might make certain foods more approachable.

Managing Food Aversions and Gag Reflexes

Living with strong food aversions can be challenging, especially in social situations or when trying to maintain a balanced diet. Fortunately, there are strategies that can help manage these reactions and potentially expand your food tolerance.

Gradual Exposure Techniques

Systematic desensitization is a psychological technique that can help overcome food aversions. This involves gradually exposing yourself to the problematic food in increasingly challenging ways. You might start by simply having the food on your plate without eating it, then progress to smelling it, touching it, taking a tiny taste, and eventually consuming small amounts.

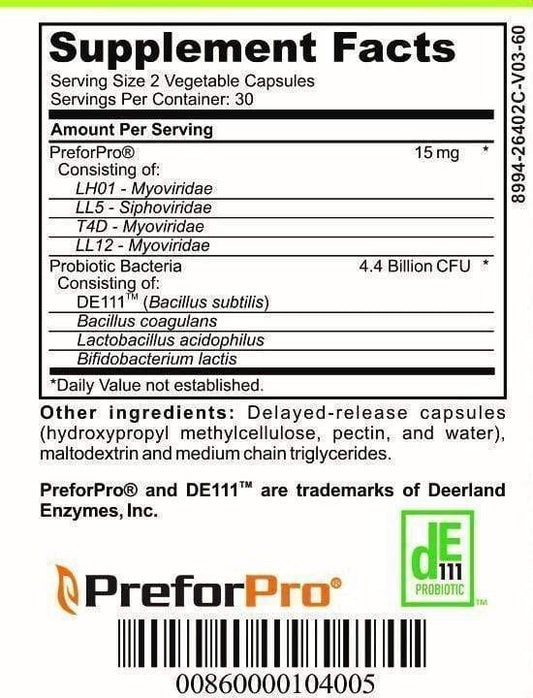

The key is to proceed at your own pace and avoid forcing yourself into situations that trigger extreme anxiety or gagging. For those with digestive sensitivities alongside psychological aversions, incorporating digestive support like Casa de Sante's digestive enzymes or probiotics can help ease the physical discomfort that might accompany trying new foods, making the exposure process more manageable.

Adaptive Cooking Methods

Sometimes, it's not the food itself but how it's prepared that triggers aversions. Experimenting with different cooking methods can transform a gag-inducing food into something palatable. Roasting vegetables brings out natural sweetness that can mask bitterness; pureeing can address texture issues; and creative seasoning can overcome bland or unpleasant flavors.

Here's a simple recipe that transforms commonly aversive Brussels sprouts into a dish even skeptics might enjoy:

Crispy Maple-Glazed Brussels Sprouts

A sweet and crispy preparation that masks the bitter notes that many find objectionable in Brussels sprouts.

Ingredients:

- 1 pound Brussels sprouts, trimmed and halved

- 2 tablespoons olive oil

- 1 tablespoon maple syrup

- 1 tablespoon balsamic vinegar

- ¼ teaspoon salt

- ⅛ teaspoon black pepper

- 2 tablespoons chopped pecans (optional)

Instructions:

- Preheat oven to 425°F (220°C).

- Toss Brussels sprouts with olive oil, salt, and pepper on a baking sheet.

- Roast for 20 minutes, stirring halfway through.

- Mix maple syrup and balsamic vinegar in a small bowl.

- Drizzle mixture over Brussels sprouts, add pecans if using, and roast for another 5 minutes until caramelized.

Prep Time: 10 minutes

Cook Time: 25 minutes

Yield: 4 servings

Cuisine: American

When Food Aversions Signal Something More

While many food aversions are simply personal preferences, sometimes they can indicate underlying conditions that deserve attention. Understanding when to seek help is important for overall health and wellbeing.

Sensory Processing Issues

For some individuals, particularly those with autism spectrum disorders or sensory processing disorders, food aversions may be part of broader sensory sensitivities. These individuals might experience tastes, textures, and smells more intensely than others, making certain foods genuinely overwhelming to their sensory systems.

In these cases, working with occupational therapists who specialize in sensory integration can be helpful. These professionals can provide strategies to gradually build tolerance while respecting sensory needs. Personalized approaches, such as Casa de Sante's personalized meal plans, can also be valuable for individuals with sensory processing issues, as they can be tailored to accommodate specific sensory preferences while ensuring nutritional adequacy.

Digestive Disorders and Food Intolerances

Sometimes what appears to be a psychological food aversion may actually be the body's response to foods that cause digestive distress. Conditions like irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), celiac disease, or food intolerances can cause uncomfortable or painful reactions that lead to learned aversions.

If you notice patterns in your food aversions – particularly if they're accompanied by symptoms like bloating, abdominal pain, or changes in bowel habits – it's worth consulting with a healthcare provider. Identifying and addressing underlying digestive issues can sometimes resolve what seemed like purely psychological food aversions.

Embracing Food Diversity While Respecting Limits

Food aversions are valid personal experiences that deserve respect, both from ourselves and others. While expanding our palates can be rewarding, it's equally important to acknowledge our limits and find balance in our approach to challenging foods.

Remember that food preferences exist on a spectrum. Some aversions may fade with time and exposure, while others might remain lifelong companions. The goal isn't necessarily to conquer every food aversion, but rather to develop a relationship with food that nourishes both body and mind while minimizing stress and discomfort.

By understanding the complex interplay of biology, psychology, and experience that shapes our food aversions, we can approach our eating habits with greater compassion and curiosity. Whether you're working to overcome a specific aversion or simply trying to understand why certain foods trigger your gag reflex, knowledge is the first step toward a more peaceful relationship with food.