What Is FODMAP Intolerance? Symptoms, Causes, and Management

What Is FODMAP Intolerance? Symptoms, Causes, and Management

If you've been experiencing digestive issues like bloating, gas, abdominal pain, or irregular bowel movements, you might have come across the term "FODMAP intolerance." This increasingly recognized digestive condition affects millions worldwide, yet many people remain undiagnosed or confused about what it actually means. Understanding FODMAP intolerance is the first step toward managing symptoms and improving your quality of life.

Unlike food allergies that trigger immune responses, FODMAP intolerance involves difficulty digesting specific types of carbohydrates found in everyday foods. These carbohydrates can cause significant discomfort when they ferment in your digestive system, leading to a range of uncomfortable and sometimes debilitating symptoms.

What Are FODMAPs?

FODMAP is an acronym that stands for Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides, And Polyols. These are scientific terms for specific types of short-chain carbohydrates and sugar alcohols that can be poorly absorbed in the small intestine. When these carbohydrates reach the large intestine undigested, they become food for gut bacteria, which ferment them and produce gas.

Breaking down the acronym further:

- Fermentable: These carbohydrates are quickly broken down (fermented) by bacteria in the gut

- Oligosaccharides: Found in foods like wheat, rye, onions, garlic, and legumes

- Disaccharides: Primarily lactose, found in dairy products

- Monosaccharides: Mainly fructose, found in honey, many fruits, and high-fructose corn syrup

- Polyols: Sugar alcohols like sorbitol and mannitol, found in some fruits and vegetables and used as artificial sweeteners

Common High-FODMAP Foods

Many everyday foods contain high levels of FODMAPs. Some of the most common high-FODMAP foods include wheat-based products (bread, pasta, cereals), dairy products containing lactose (milk, ice cream, soft cheeses), certain fruits (apples, pears, mangoes, watermelon), specific vegetables (onions, garlic, mushrooms, cauliflower), legumes (beans, lentils, chickpeas), and sweeteners like honey and high-fructose corn syrup.

It's important to note that FODMAPs are not inherently unhealthy. In fact, many high-FODMAP foods are nutritious and beneficial for people who can tolerate them. The problem only arises when someone has difficulty digesting these specific carbohydrates.

Symptoms of FODMAP Intolerance

FODMAP intolerance can manifest through a variety of digestive symptoms that typically appear within a few hours after consuming high-FODMAP foods. The severity and combination of symptoms vary widely from person to person, making the condition sometimes difficult to identify without proper testing or an elimination diet.

Common Digestive Symptoms

The most frequently reported symptoms of FODMAP intolerance include bloating and abdominal distension, which can be severe enough to make clothing uncomfortable. Many people also experience excessive gas, cramping, and abdominal pain that can range from mild discomfort to sharp, intense pain. Bowel habit changes are common too, with some people experiencing diarrhea, constipation, or sometimes alternating between both.

Other digestive symptoms may include nausea, feeling uncomfortably full after eating small amounts of food, and audible gurgling or rumbling sounds from the abdomen (borborygmi). These symptoms typically worsen after meals containing high-FODMAP foods and may improve after bowel movements.

Non-Digestive Symptoms

While digestive issues are the primary symptoms, FODMAP intolerance can also lead to several non-digestive symptoms that significantly impact quality of life. Many people report fatigue and low energy levels, which may result from the body's stress response to ongoing digestive discomfort or from nutritional deficiencies if the diet becomes restricted.

Some individuals experience brain fog, difficulty concentrating, or headaches. There's also growing evidence suggesting connections between gut health and mood, with some FODMAP-intolerant individuals reporting increased anxiety or low mood when symptoms flare up. Sleep disturbances are common too, as digestive discomfort can make it difficult to fall or stay asleep.

Causes and Risk Factors

FODMAP intolerance isn't caused by a single factor but rather results from a combination of physiological mechanisms that affect how the digestive system processes certain carbohydrates. Understanding these mechanisms can help explain why some people develop symptoms while others can consume high-FODMAP foods without issues.

Physiological Mechanisms

The primary mechanism behind FODMAP intolerance involves poor absorption of these carbohydrates in the small intestine. In people with FODMAP sensitivity, these carbohydrates pass through the small intestine without being properly broken down and absorbed. When they reach the large intestine, gut bacteria rapidly ferment them, producing hydrogen, carbon dioxide, and methane gases that cause bloating, pain, and altered bowel movements.

Additionally, FODMAPs are osmotically active, meaning they draw water into the intestine. This increased fluid can contribute to diarrhea in some individuals and explains why symptoms can appear relatively quickly after consuming problematic foods. The combination of gas production and increased intestinal fluid creates the perfect storm for digestive discomfort.

Connection to IBS

FODMAP intolerance is particularly common among people with Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS). In fact, studies suggest that up to 75% of people with IBS experience improvement in symptoms when following a low-FODMAP diet. This strong connection has led many gastroenterologists to recommend low-FODMAP diets as a first-line treatment approach for IBS patients.

However, it's important to understand that FODMAP intolerance and IBS are not the same condition. IBS is a functional gastrointestinal disorder diagnosed based on specific criteria (the Rome criteria), while FODMAP intolerance specifically refers to difficulty digesting these particular carbohydrates. Many people with FODMAP sensitivity don't meet the criteria for an IBS diagnosis, and some IBS patients may have triggers beyond FODMAPs.

Genetic and Environmental Factors

Research suggests there may be genetic components to FODMAP sensitivity, particularly regarding lactose and fructose malabsorption. Some ethnic groups have higher rates of lactose intolerance; for example, it's estimated that 65-70% of the global population has some degree of lactose intolerance, with higher rates in East Asian, African, and Hispanic populations.

Environmental factors also play a role. Gastrointestinal infections, stress, antibiotics, and other factors that disrupt the gut microbiome can potentially trigger or worsen FODMAP sensitivity. Some people develop temporary FODMAP intolerance following a bout of gastroenteritis (commonly known as "stomach flu"), a phenomenon sometimes called post-infectious IBS.

Diagnosis of FODMAP Intolerance

Diagnosing FODMAP intolerance can be challenging because symptoms overlap with many other digestive conditions. There's no single definitive test for FODMAP sensitivity as a whole, though there are tests for specific types of carbohydrate malabsorption.

Medical Evaluation

The first step in diagnosis typically involves a comprehensive medical evaluation to rule out other conditions that could cause similar symptoms. Your doctor might recommend tests to exclude celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, microscopic colitis, pancreatic insufficiency, or other digestive disorders. This evaluation may include blood tests, stool tests, endoscopy, colonoscopy, or imaging studies depending on your specific symptoms and medical history.

It's crucial not to self-diagnose FODMAP intolerance and eliminate food groups without medical guidance, as restrictive diets can lead to nutritional deficiencies and may mask underlying conditions that require different treatment approaches.

Elimination Diet and Food Challenge

The gold standard for diagnosing FODMAP intolerance is an elimination diet followed by systematic food challenges. This process typically begins with a strict low-FODMAP diet for 2-6 weeks under the guidance of a registered dietitian. If symptoms significantly improve during this elimination phase, it suggests FODMAPs may be triggering your symptoms.

The next phase involves methodically reintroducing specific FODMAP groups one at a time while monitoring symptoms. This helps identify which particular FODMAPs cause problems and at what quantities. The goal isn't typically to maintain a strict low-FODMAP diet long-term but rather to identify personal triggers and thresholds.

Managing FODMAP Intolerance

The good news is that FODMAP intolerance can be effectively managed through dietary modifications and lifestyle changes. With proper guidance, most people can significantly reduce symptoms while maintaining a nutritious, varied diet.

The Low-FODMAP Diet Approach

The low-FODMAP diet is a three-phase process developed by researchers at Monash University in Australia. The first phase involves strict elimination of high-FODMAP foods for a short period (typically 2-6 weeks). The second phase is a systematic reintroduction of FODMAP subgroups to identify specific triggers. The final phase is personalization, where you develop a modified diet that avoids only the FODMAPs that trigger your symptoms.

Working with a registered dietitian who specializes in digestive health is highly recommended when following this approach. They can help ensure nutritional adequacy, guide you through the reintroduction process, and help interpret your body's responses to different foods. Many people find they can tolerate certain FODMAPs in small amounts or specific contexts, making the diet less restrictive over time.

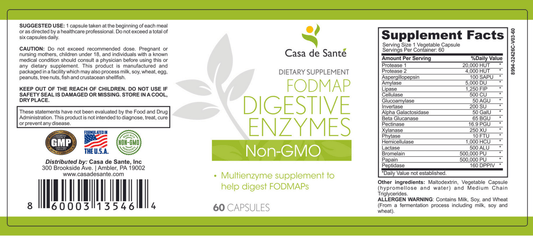

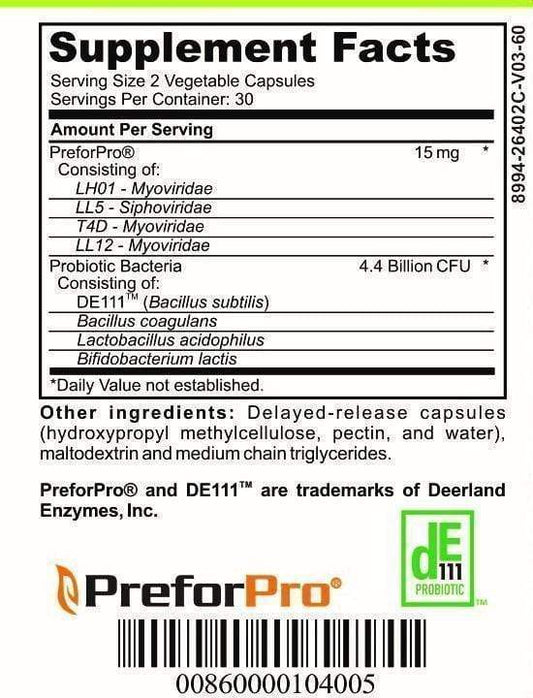

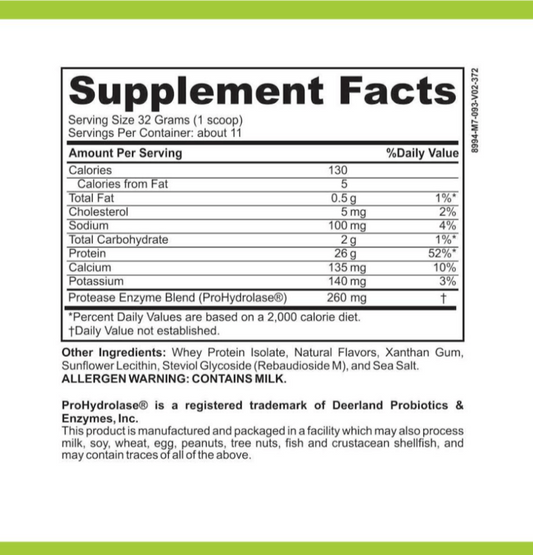

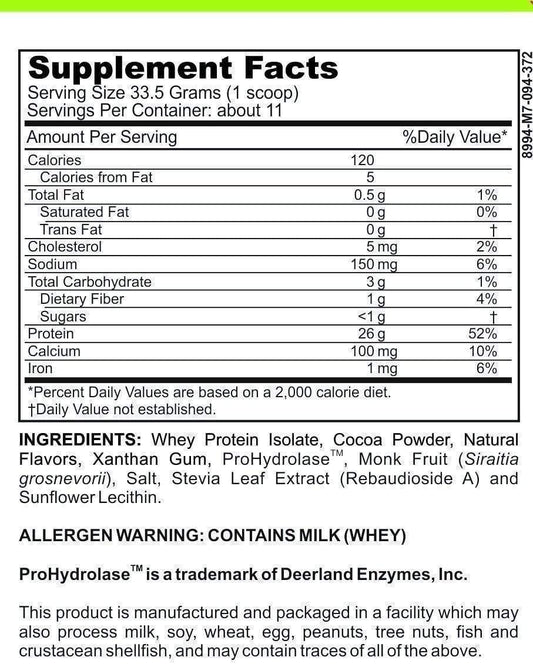

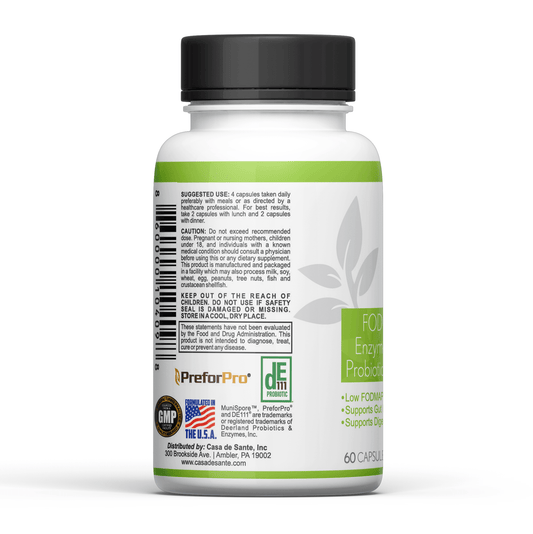

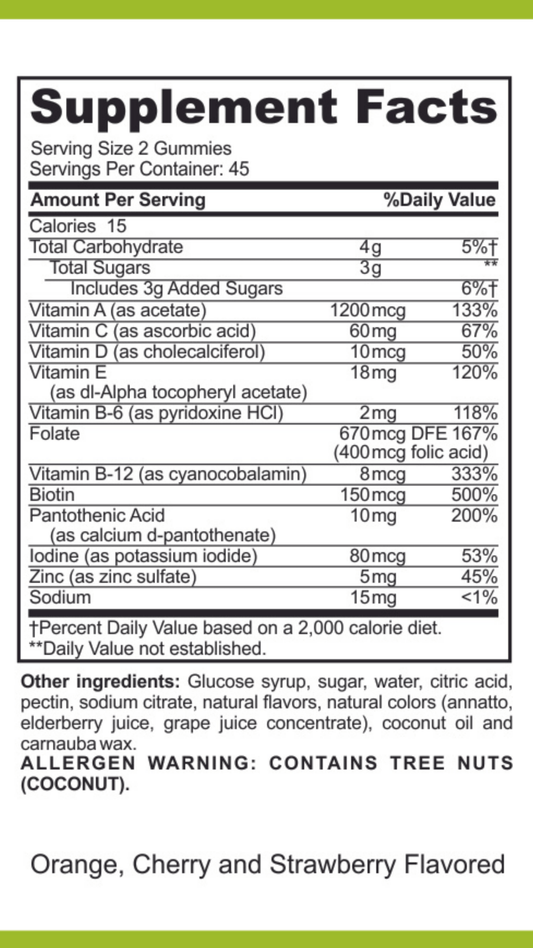

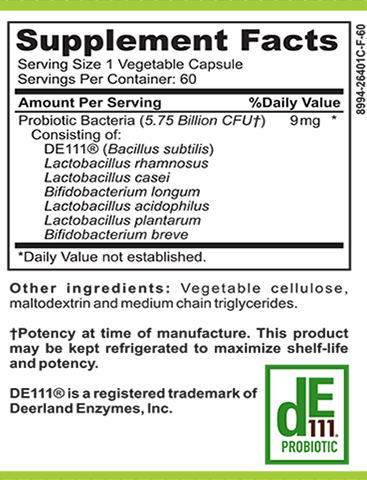

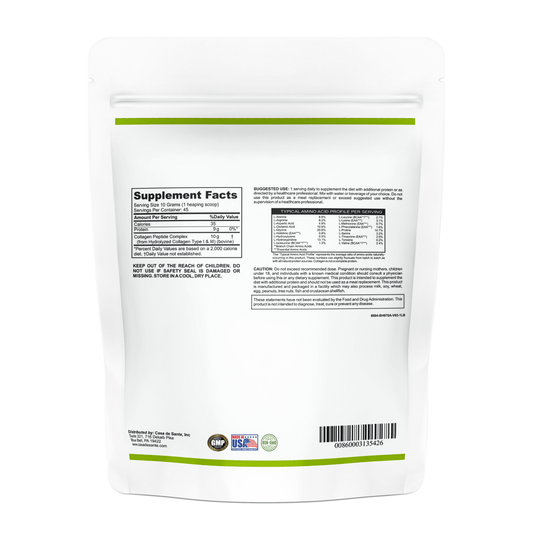

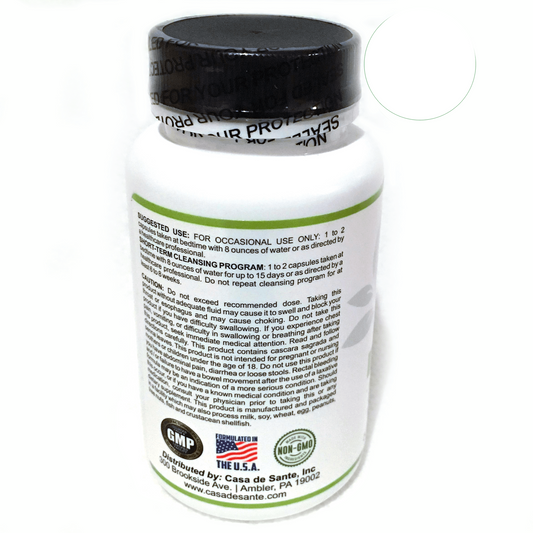

Supplements and Medications

Several supplements may help manage FODMAP intolerance symptoms. Digestive enzymes like lactase (for lactose intolerance) or alpha-galactosidase (for oligosaccharides in beans) can help break down specific FODMAPs. Peppermint oil capsules have shown benefit for some IBS symptoms, particularly abdominal pain. Probiotics may help some individuals, though research on specific strains for FODMAP intolerance is still emerging.

For persistent symptoms, medications might be recommended by your healthcare provider. These could include antispasmodics for pain, laxatives for constipation, anti-diarrheal agents, or low-dose antidepressants that can help regulate gut nerve sensitivity at doses lower than those used for depression treatment.

Lifestyle Modifications

Beyond dietary changes, several lifestyle modifications can help manage FODMAP intolerance. Stress management techniques are particularly important since stress can trigger or worsen digestive symptoms. Regular physical activity has been shown to improve gut motility and reduce bloating. Mindful eating practices—eating slowly, chewing thoroughly, and avoiding large meals—can also help minimize symptoms.

Adequate hydration and establishing regular meal times may help regulate bowel function. Some people also find that certain cooking methods, like soaking legumes before cooking or fermenting foods, can reduce their FODMAP content and improve tolerability.

Living Well with FODMAP Intolerance

While FODMAP intolerance can be challenging, most people can achieve significant symptom improvement with proper management. The key is to work with healthcare professionals to develop a personalized approach that addresses your specific triggers and needs. With time and patience, you can identify your personal tolerance thresholds and expand your diet to include as many foods as possible while keeping symptoms under control.

Remember that FODMAP sensitivity can fluctuate over time and with different life circumstances. What triggers symptoms during high-stress periods might be well-tolerated during more relaxed times. By understanding your body's signals and working with healthcare providers, you can develop strategies to enjoy food, social occasions, and life despite FODMAP intolerance.