Understanding Oligosaccharides: Key Components of the FODMAP Diet

Understanding Oligosaccharides: Key Components of the FODMAP Diet

If you've been exploring dietary solutions for digestive issues, you've likely encountered the FODMAP diet. This increasingly popular approach to managing irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and other functional gastrointestinal disorders involves limiting certain fermentable carbohydrates. Among these carbohydrates, oligosaccharides stand out as particularly problematic for many people with sensitive digestive systems. But what exactly are these compounds, and why do they matter so much in the context of digestive health?

What Are Oligosaccharides?

Oligosaccharides are a type of carbohydrate made up of small chains of sugar molecules, typically containing between 3 and 10 simple sugars linked together. The name comes from the Greek words "oligo" (few) and "saccharide" (sugar). Unlike simple sugars such as glucose or fructose, which are rapidly absorbed in the small intestine, oligosaccharides have chemical bonds that human digestive enzymes cannot break down efficiently.

This resistance to digestion means that oligosaccharides pass largely intact into the large intestine, where they become food for gut bacteria. While this bacterial fermentation is a normal and often beneficial process, it produces gases like hydrogen, carbon dioxide, and methane that can lead to uncomfortable symptoms in sensitive individuals.

The structural complexity of oligosaccharides is what gives them their unique properties in the digestive system. These carbohydrates feature specific glycosidic bonds between their constituent sugar molecules, creating branched or linear chains with diverse configurations. This molecular architecture not only determines how they interact with digestive enzymes but also influences which bacterial species can metabolize them in the colon. For instance, some oligosaccharides preferentially feed beneficial Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli, which is why certain types are classified as prebiotics and are increasingly added to functional foods and supplements.

Interestingly, oligosaccharides occur naturally in human breast milk, where they play crucial roles in infant gut development and immunity. These human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs) represent the third most abundant component in breast milk after lactose and fat, highlighting their evolutionary importance. They help establish beneficial gut flora in newborns and protect against pathogens by preventing bacterial adhesion to intestinal cell surfaces. This natural presence in breast milk underscores that oligosaccharides aren't inherently problematic—it's their concentration and an individual's gut sensitivity that determines whether they cause digestive discomfort.

Types of Oligosaccharides in the FODMAP Diet

In the context of the FODMAP diet, two main types of oligosaccharides are of particular concern: fructans and galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS). Fructans consist of chains of fructose molecules with a glucose molecule at one end. Common examples include inulin and fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS). Galacto-oligosaccharides, on the other hand, contain chains of galactose sugars, often with a glucose molecule attached. The most well-known GOS are raffinose and stachyose, found abundantly in legumes.

Both types share the common characteristic of being poorly absorbed in the small intestine, making them highly fermentable by colonic bacteria. This fermentation process is what gives oligosaccharides their status as the "O" in the FODMAP acronym, which stands for Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides, And Polyols.

Why Can't We Digest Them?

Humans lack the enzyme alpha-galactosidase needed to break down the bonds in galacto-oligosaccharides. Similarly, we don't produce enough of the enzymes required to fully digest fructans. This enzymatic limitation is universal in humans – it's not a deficiency or disorder but simply part of our biology. The difference lies in how sensitive people are to the effects of bacterial fermentation of these undigested carbohydrates.

Common Food Sources of Oligosaccharides

Oligosaccharides are widespread in our food supply, appearing in many plant-based foods that are otherwise considered nutritious. Understanding where these compounds lurk is essential for anyone following a low-FODMAP diet.

Fructan-Rich Foods

Wheat and wheat-based products represent one of the most significant sources of fructans in the Western diet. This includes bread, pasta, couscous, and many baked goods. However, it's important to note that it's the fructans in wheat – not gluten – that trigger digestive symptoms in many IBS sufferers.

Other major sources of fructans include onions and garlic, which contain particularly high concentrations. Even small amounts of these ingredients can trigger symptoms in sensitive individuals. Additional fructan-containing foods include leeks, spring onions (the white parts), shallots, barley, rye, artichokes, chicory root, and inulin (often added as a prebiotic fiber to "health" foods).

Galacto-oligosaccharide (GOS) Sources

Legumes stand as the primary dietary source of GOS. This food group includes beans (kidney, black, pinto, navy), chickpeas, lentils, and soybeans. The notorious digestive effects of beans – often joked about in popular culture – are largely due to their high GOS content.

Other sources include certain nuts like pistachios and cashews. Some vegetables, such as cabbage and Brussels sprouts, contain smaller amounts of GOS alongside other FODMAPs, contributing to their reputation as gas-producing foods.

Health Effects of Oligosaccharides

The impact of oligosaccharides on health presents an interesting paradox. For many people, these compounds offer significant health benefits, while for others – particularly those with IBS or similar conditions – they can trigger uncomfortable and sometimes debilitating symptoms.

Benefits as Prebiotics

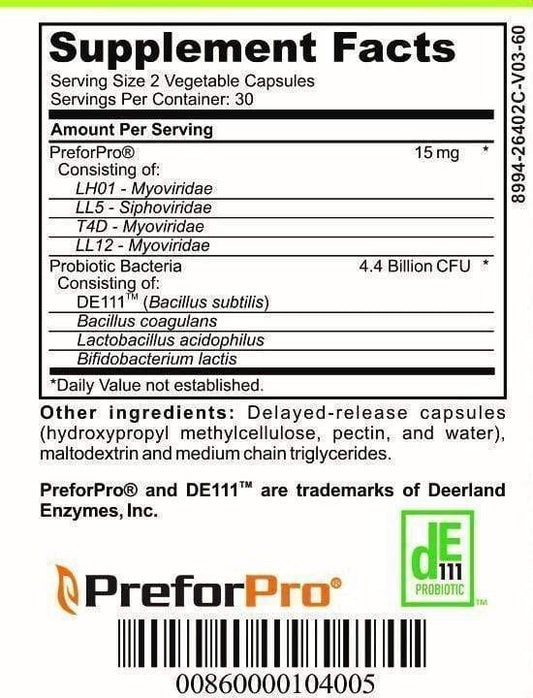

Oligosaccharides are considered prebiotics – non-digestible food ingredients that beneficially affect the host by selectively stimulating the growth and/or activity of beneficial bacteria in the colon. When oligosaccharides ferment in the large intestine, they promote the growth of beneficial bacteria like Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli, which can help maintain a healthy gut microbiome.

This prebiotic effect has been associated with numerous health benefits, including improved immune function, enhanced mineral absorption (particularly calcium and magnesium), and potentially reduced risk of certain cancers, particularly colorectal cancer. Additionally, the short-chain fatty acids produced during fermentation serve as an energy source for colon cells and may help regulate inflammation.

Symptoms in Sensitive Individuals

Despite their benefits, oligosaccharides can cause significant discomfort in people with IBS and other functional gut disorders. The bacterial fermentation of these carbohydrates produces gases that can lead to bloating, abdominal pain, flatulence, and altered bowel habits (both diarrhea and constipation). For some individuals, these symptoms can be severe enough to impact quality of life and daily functioning.

The severity of symptoms depends on several factors, including the amount consumed, individual sensitivity, gut microbiome composition, and the presence of other digestive conditions. Some people may tolerate small amounts of oligosaccharides without issues but experience symptoms when consuming larger quantities or when combining multiple sources in the same meal.

Managing Oligosaccharides in Your Diet

For those with IBS or FODMAP sensitivity, managing oligosaccharide intake becomes an important aspect of symptom control. However, this doesn't necessarily mean eliminating these compounds entirely from your diet.

The Low-FODMAP Approach

The low-FODMAP diet, developed by researchers at Monash University in Australia, offers a systematic approach to identifying and managing FODMAP sensitivities. This diet involves three phases: elimination, reintroduction, and personalization. During the elimination phase (typically 2-6 weeks), all high-FODMAP foods, including those high in oligosaccharides, are removed from the diet.

The reintroduction phase systematically tests tolerance to specific FODMAP groups, including fructans and GOS. This process helps identify which specific FODMAPs trigger symptoms and at what quantities. Finally, the personalization phase involves developing a long-term, sustainable diet that avoids problematic FODMAPs while maintaining as much dietary variety as possible.

Practical Tips for Reducing Oligosaccharides

Several practical strategies can help reduce oligosaccharide intake while maintaining a nutritious diet. Soaking and sprouting legumes can reduce their GOS content, making them more tolerable for some individuals. Similarly, cooking onions and garlic in oil and then removing the solids (while keeping the flavored oil) allows you to enjoy their flavor without consuming the water-soluble fructans.

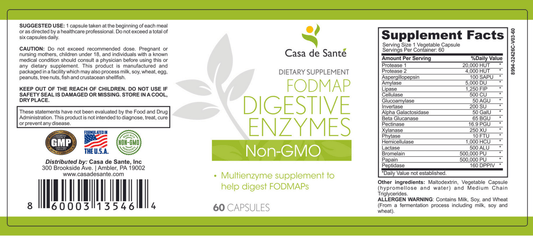

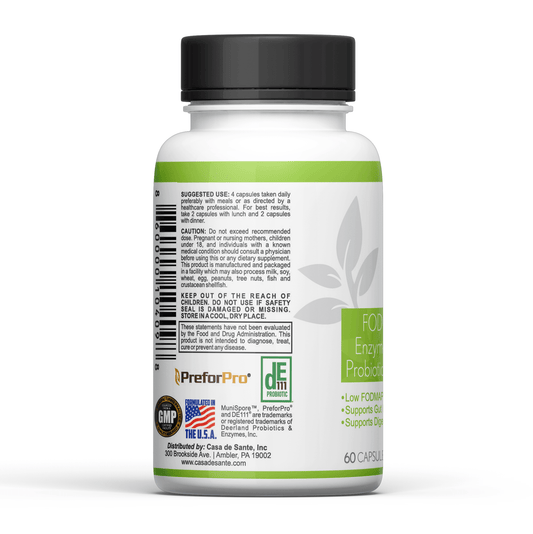

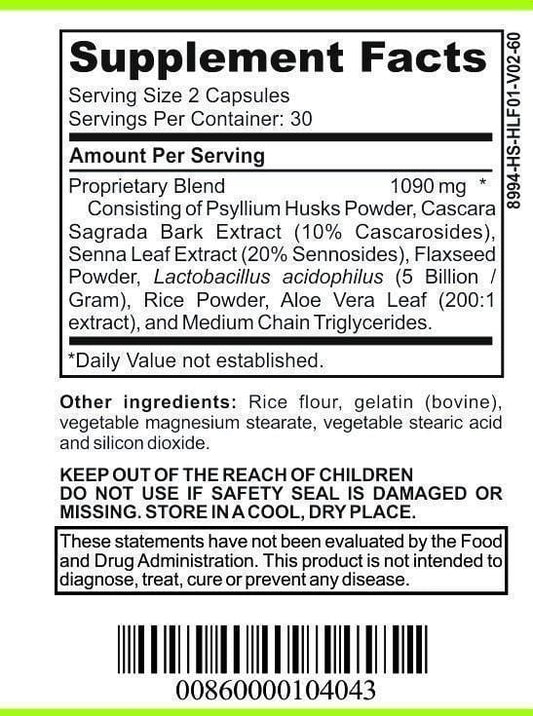

Enzyme supplements containing alpha-galactosidase (such as Beano) may help some people digest GOS more effectively, though results vary. For fructans, no equivalent enzyme supplement is widely available, though research in this area continues. Fermented versions of high-FODMAP foods, such as sourdough bread instead of regular wheat bread, may also be better tolerated as the fermentation process pre-digests some of the problematic carbohydrates.

Balancing Digestive Comfort with Nutritional Needs

While managing oligosaccharide intake can significantly improve symptoms for many people with IBS, it's important to consider the nutritional implications of restricting these foods long-term.

Nutritional Considerations

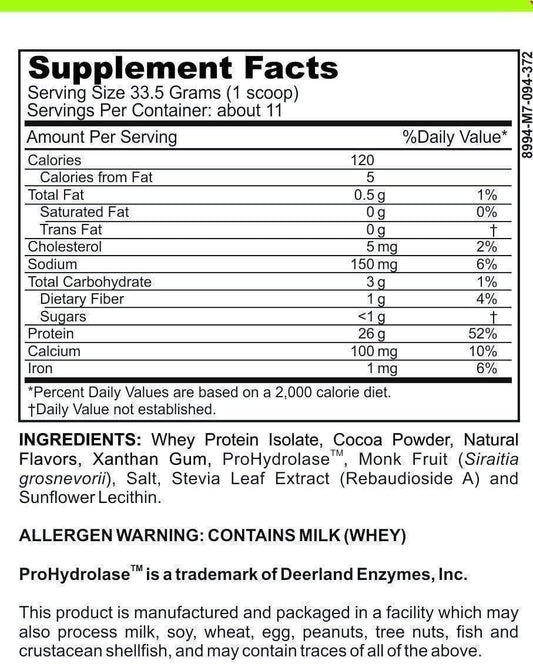

Many oligosaccharide-rich foods are nutritional powerhouses, providing essential vitamins, minerals, protein, and fiber. Legumes, for instance, offer plant-based protein, iron, zinc, and folate. Whole grains provide B vitamins, minerals, and fiber. Completely eliminating these food groups could potentially lead to nutritional gaps.

Working with a registered dietitian who specializes in digestive health can help ensure that your diet remains nutritionally adequate while managing symptoms. They can suggest suitable alternatives and help you determine your personal tolerance thresholds, allowing you to include small amounts of oligosaccharide-containing foods if possible.

The Importance of Microbiome Diversity

Another consideration is the impact of long-term oligosaccharide restriction on gut microbiome diversity. Since these compounds act as prebiotics, significantly reducing them may alter the composition of gut bacteria over time. Some research suggests that very restrictive low-FODMAP diets maintained long-term might reduce beneficial bacteria populations.

For this reason, the current recommendation is to liberalize the diet as much as possible after the initial elimination and testing phases. This might mean including small amounts of oligosaccharide-containing foods that are below your personal threshold for triggering symptoms, or periodically consuming these foods when symptoms are well-controlled.

Conclusion

Oligosaccharides represent a fascinating nutritional paradox – beneficial prebiotics for many, yet troublesome triggers for others. Understanding their role in the FODMAP diet can help those with digestive sensitivities make informed choices about their diet while maintaining optimal nutrition.

For people with IBS and similar conditions, finding the right balance with oligosaccharides often involves personalized approaches rather than complete elimination. With careful attention to individual tolerance levels and thoughtful dietary planning, it's possible to manage symptoms while still enjoying a diverse and nutritious diet. As research in this area continues to evolve, we may discover even more effective strategies for harnessing the benefits of these complex carbohydrates while minimizing their potential drawbacks.