The Role of Fructans in Wheat: Health Implications and Dietary Considerations

The Role of Fructans in Wheat: Health Implications and Dietary Considerations

Wheat has been a dietary staple for thousands of years, feeding civilizations and forming the backbone of countless culinary traditions worldwide. Yet in recent decades, this ancient grain has become increasingly controversial, with many people reporting digestive discomfort and other symptoms after consuming wheat products. While gluten often takes center stage in these discussions, another component of wheat—fructans—deserves significant attention for its profound effects on human health. These complex carbohydrates play crucial roles both in the wheat plant itself and in human digestive processes, with implications that extend far beyond simple nutrition.

Understanding Fructans: Structure and Function

Fructans are chains of fructose molecules linked together with a terminal glucose unit. In wheat, the predominant type of fructan is inulin, which consists of linear chains of fructose molecules. These compounds serve as storage carbohydrates in the wheat plant, helping it survive environmental stresses and providing energy reserves during germination and growth.

Unlike simple sugars that are readily digested and absorbed in the small intestine, fructans resist digestion because humans lack the enzymes necessary to break the specific bonds between fructose molecules. This resistance to digestion classifies fructans as fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAPs), a group of short-chain carbohydrates that can trigger digestive symptoms in sensitive individuals.

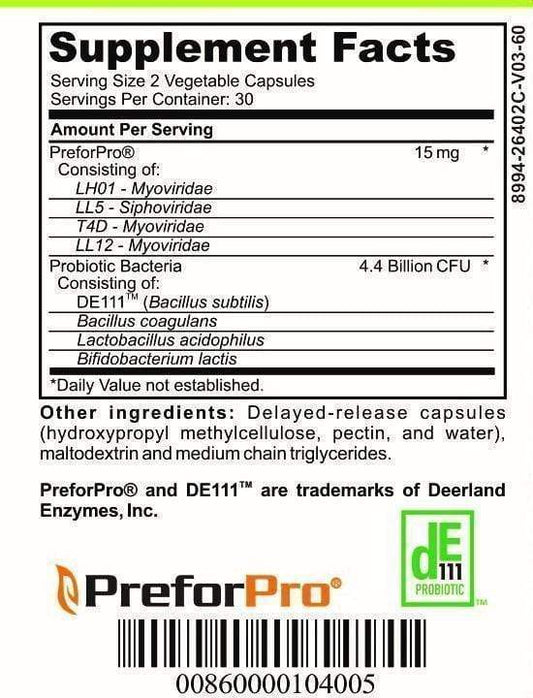

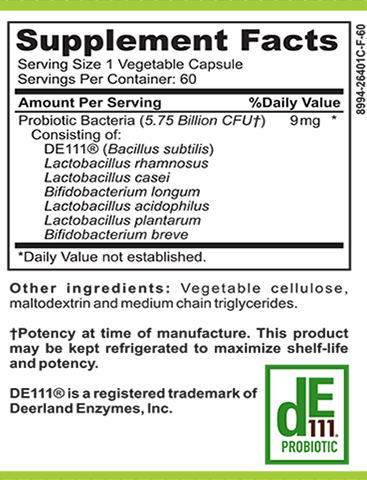

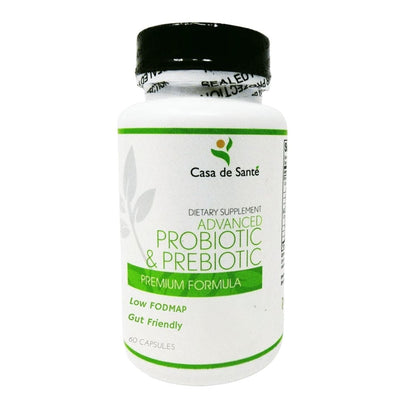

The molecular structure of fructans plays a crucial role in their biological function. The β(2→1) linkages between fructose units create a configuration that bacterial enzymes in the large intestine can break down, but human digestive enzymes cannot. This structural characteristic is what allows fructans to function as prebiotics, compounds that selectively stimulate the growth and activity of beneficial gut bacteria. When fructans reach the colon undigested, they become food for probiotic bacteria like Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli, which ferment these carbohydrates and produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as butyrate, acetate, and propionate. These SCFAs provide energy to colonocytes, help maintain gut barrier integrity, and may have anti-inflammatory effects throughout the body.

The degree of polymerization (DP)—the number of fructose units in the chain—also affects how fructans behave in both plants and the human digestive system. Wheat fructans typically have a DP ranging from 3 to 19, with most falling between 5 and 12. Fructans with lower DP tend to be more rapidly fermented in the proximal colon, while those with higher DP are fermented more slowly throughout the colon. This variation in fermentation rates and locations may partially explain why individuals with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or other functional gut disorders experience different symptom patterns when consuming various fructan-containing foods.

Fructan Content in Different Wheat Products

The fructan content in wheat products varies considerably depending on the wheat variety, growing conditions, and processing methods. Modern wheat varieties typically contain between 1-4% fructans by weight, with hard wheat varieties generally containing higher levels than soft wheat. Processing can significantly alter fructan content—bread making, for instance, reduces fructan levels as yeast fermentation consumes some of these carbohydrates during the rising process.

Interestingly, ancient wheat varieties like einkorn and emmer tend to contain lower levels of fructans compared to modern wheat cultivars. This difference partly explains why some people who experience digestive discomfort with conventional wheat products can tolerate ancient grains. Refined wheat products generally contain fewer fructans than whole wheat options, as fructans are concentrated in the outer layers of the wheat kernel that are removed during refining.

Fructans and Digestive Health

When fructans reach the large intestine undigested, they become food for gut bacteria, which ferment these carbohydrates and produce gases like hydrogen, carbon dioxide, and methane. This fermentation process is a double-edged sword for human health—beneficial for some while problematic for others.

For many people, the bacterial fermentation of fructans promotes a healthy gut microbiome by supporting the growth of beneficial bacteria like Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli. These bacteria produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as butyrate, which nourishes colon cells, strengthens the intestinal barrier, and helps regulate inflammation. This prebiotic effect of fructans can contribute to improved digestive health and potentially offer protection against colorectal cancer and inflammatory bowel diseases.

Fructan Sensitivity and IBS

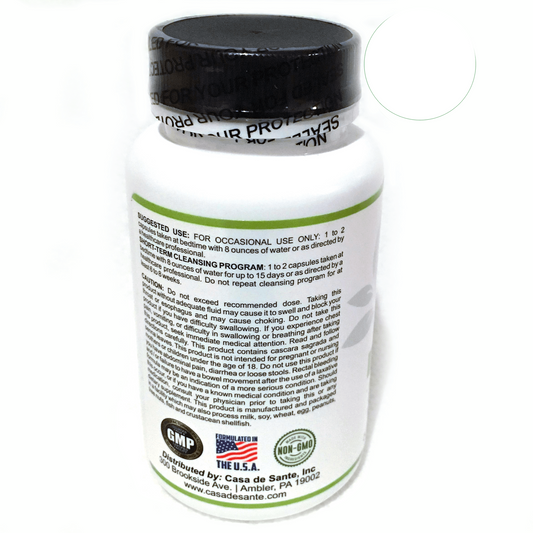

Despite their potential benefits, fructans can trigger significant digestive distress in sensitive individuals, particularly those with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Research suggests that up to 75% of IBS patients experience symptom improvement when reducing dietary fructans. The fermentation of fructans in these individuals can lead to excessive gas production, bloating, abdominal pain, and altered bowel habits—the hallmark symptoms of IBS.

What's particularly noteworthy is that many people who believe they have non-celiac gluten sensitivity may actually be reacting to fructans rather than gluten. Several studies have demonstrated that when individuals self-diagnosed with gluten sensitivity consume pure gluten (without fructans), many experience no symptoms. However, when they consume fructans, their symptoms return, suggesting fructan sensitivity as the underlying issue.

The FODMAP Connection

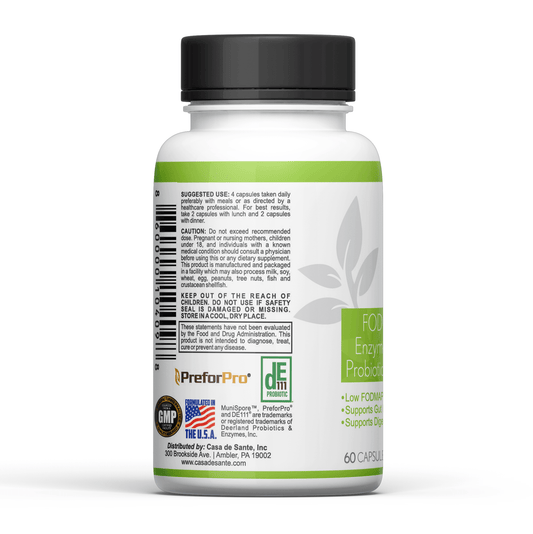

Fructans represent just one category within the broader FODMAP family. The low-FODMAP diet, which restricts multiple fermentable carbohydrates including fructans, has emerged as one of the most effective dietary interventions for IBS, with success rates of 50-80% in clinical trials. This approach involves temporarily eliminating high-FODMAP foods (including wheat products) and then systematically reintroducing them to identify specific triggers and tolerance thresholds.

For those sensitive to fructans, the challenge extends beyond wheat products. Fructans are also present in onions, garlic, artichokes, chicory root, and many other plant foods. This widespread distribution makes complete avoidance difficult but underscores the importance of personalized approaches to dietary management rather than blanket elimination of entire food groups.

Fructans and Immune Function

Beyond their direct effects on digestive processes, fructans appear to influence immune function through multiple mechanisms. The SCFAs produced during fructan fermentation help regulate immune responses and maintain the integrity of the intestinal barrier, potentially reducing the risk of autoimmune conditions and allergies.

Research indicates that adequate fructan consumption may help prevent excessive intestinal permeability—sometimes called "leaky gut"—which has been implicated in various inflammatory and autoimmune conditions. By supporting the growth of beneficial bacteria and promoting SCFA production, fructans contribute to a balanced immune environment in the gut, which can have systemic effects throughout the body.

Fructans and Inflammation

The relationship between fructans and inflammation is complex and sometimes contradictory. For individuals with normal fructan tolerance, these compounds may help reduce systemic inflammation through their prebiotic effects and promotion of anti-inflammatory metabolites. Studies have shown associations between adequate fructan intake and reduced markers of inflammation in healthy individuals.

Conversely, in fructan-sensitive people, consuming these carbohydrates can trigger inflammatory responses in the intestine, potentially contributing to both local and systemic inflammation. This dichotomy highlights the importance of personalized nutrition approaches that consider individual responses rather than universal dietary recommendations.

Practical Dietary Considerations

For those experiencing digestive symptoms after consuming wheat products, determining whether fructans are the culprit requires a systematic approach. Unlike celiac disease, which can be diagnosed through specific blood tests and intestinal biopsies, fructan sensitivity lacks definitive diagnostic markers. Instead, elimination and challenge protocols remain the gold standard for identification.

Working with a registered dietitian to implement a properly structured low-FODMAP diet can help identify specific triggers and establish personal tolerance thresholds. This approach is preferable to self-diagnosis and arbitrary food restrictions, which can lead to nutritional deficiencies and unnecessary dietary limitations.

Alternative Grain Options

For individuals sensitive to wheat fructans, several alternative grains and pseudocereals offer nutritious options with lower fructan content. Sourdough bread, particularly those with long fermentation times, contains significantly reduced fructan levels as the bacteria and yeast consume these carbohydrates during the fermentation process. Many people who cannot tolerate conventional bread find sourdough digestible and enjoyable.

Other low-fructan grain options include rice, corn, quinoa, buckwheat, and millet. These alternatives can provide the nutritional benefits and culinary versatility of grains without triggering fructan-related symptoms. Oats contain moderate amounts of fructans but are often well-tolerated in small portions by those with mild sensitivity.

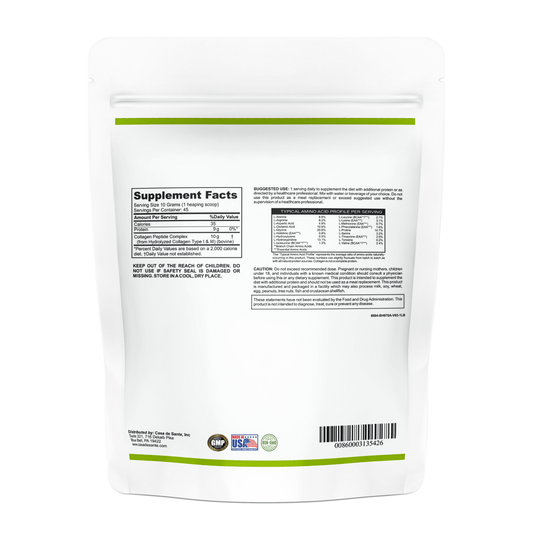

Balancing Nutritional Needs

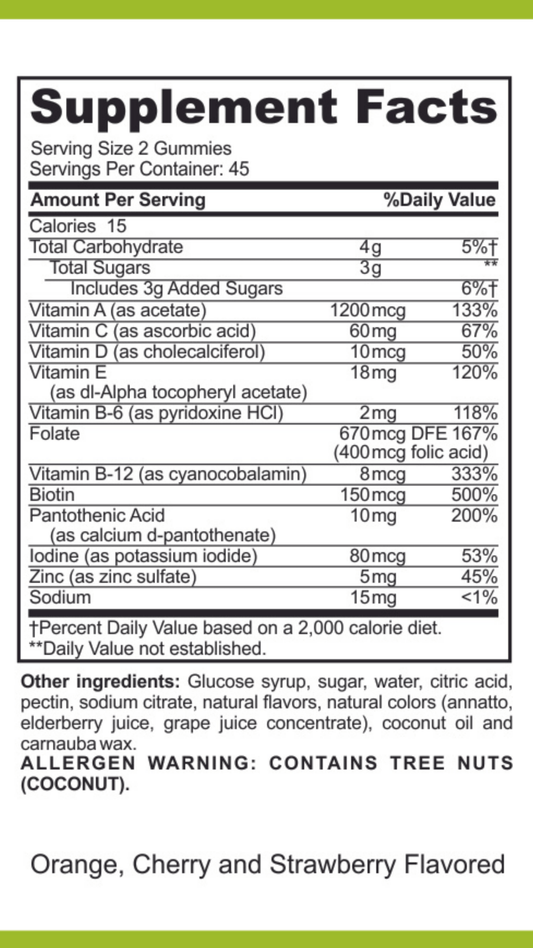

When reducing wheat consumption due to fructan sensitivity, ensuring adequate fiber intake becomes particularly important. Wheat provides significant dietary fiber for many people, and eliminating it without appropriate substitutions can lead to reduced fiber consumption. Incorporating low-FODMAP fiber sources such as chia seeds, flaxseeds, specific fruits (like oranges and strawberries), and vegetables (such as carrots and zucchini) can help maintain digestive health and microbiome diversity.

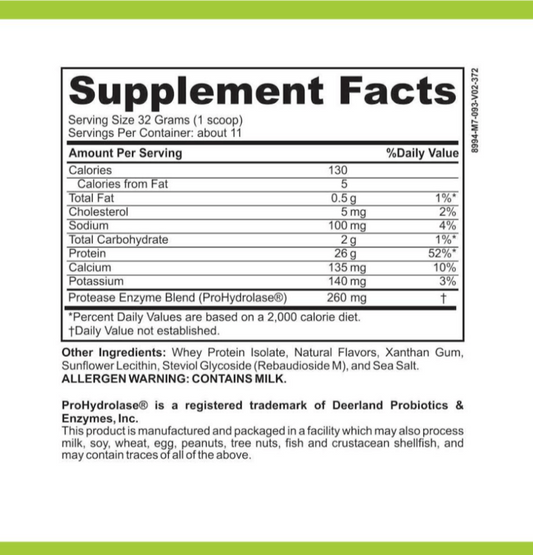

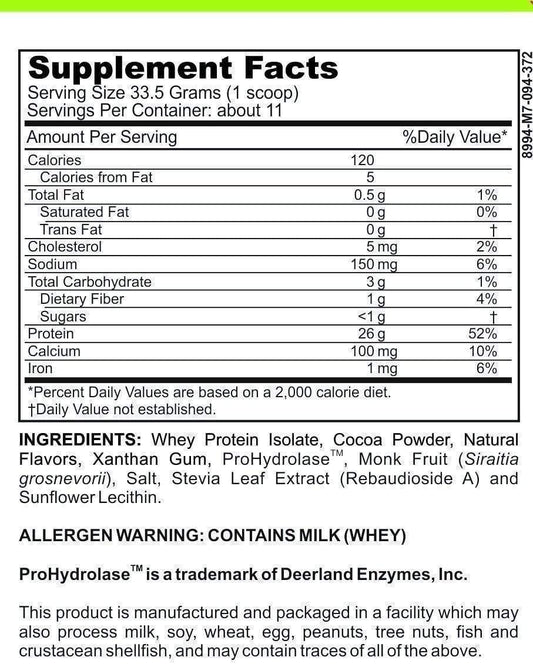

Nutritional adequacy also requires attention to B-vitamins, iron, and other nutrients commonly obtained from fortified wheat products. Diversifying the diet with nutrient-dense alternatives and, in some cases, appropriate supplementation can prevent deficiencies while managing fructan intake.

Future Directions in Fructan Research

The scientific understanding of fructans and their health effects continues to evolve rapidly. Emerging research focuses on several promising areas that may transform how we approach these compounds in our diet and health management strategies.

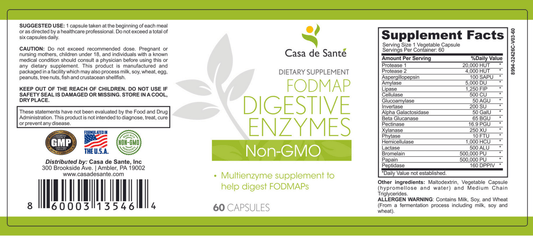

Enzyme supplements that break down fructans in the digestive tract represent one exciting avenue of development. Similar to lactase supplements for lactose intolerance, these products aim to reduce fructan-related symptoms by degrading these carbohydrates before they reach the large intestine. While preliminary studies show promise, more research is needed to optimize efficacy and identify appropriate candidates for enzyme therapy.

Personalized Approaches to Fructan Tolerance

Perhaps the most promising direction in fructan research involves personalized nutrition approaches based on individual microbiome composition and genetic factors. Evidence suggests that gut microbiome profiles strongly influence how people respond to fructans, with certain bacterial populations enhancing tolerance while others exacerbate symptoms.

Advances in microbiome testing and analysis may eventually allow for highly personalized dietary recommendations that consider an individual's unique bacterial ecosystem rather than applying one-size-fits-all restrictions. Such approaches could help maximize the potential benefits of fructans while minimizing adverse effects in sensitive individuals.

As our understanding of fructans continues to deepen, the simplistic view of these compounds as either "good" or "bad" gives way to a more nuanced perspective that recognizes both their potential benefits and challenges. For many people, moderate fructan consumption supports gut health and overall wellbeing, while others require careful management of these fermentable carbohydrates to maintain digestive comfort and quality of life. This balanced understanding, coupled with personalized approaches to diet and nutrition, offers the most promising path forward in harnessing the complex relationship between fructans, wheat, and human health.