SIBO Breath Test vs. H. Pylori Test: Understanding the Key Differences

SIBO Breath Test vs. H. Pylori Test: Understanding the Key Differences

Digestive disorders can significantly impact quality of life, making proper diagnosis essential for effective treatment. Two common tests used to identify gastrointestinal issues are the Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) breath test and the Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) test. While both involve detecting bacterial issues in the digestive system, they target different conditions and use distinct methodologies. Understanding these differences is crucial for patients experiencing digestive symptoms and healthcare providers seeking accurate diagnoses.

What is SIBO?

Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) occurs when excessive bacteria colonize the small intestine—an area that should have relatively low bacterial counts compared to the colon. This overgrowth disrupts normal digestive processes and can lead to uncomfortable symptoms including bloating, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and malabsorption of nutrients.

SIBO often develops when the natural mechanisms that control bacterial populations in the small intestine malfunction. This can happen due to structural abnormalities, reduced intestinal motility, or complications from surgeries. People with conditions like irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), Crohn's disease, or those who have undergone gastric bypass surgery are at higher risk for developing SIBO.

The microbiome imbalance in SIBO can be particularly disruptive because the small intestine is primarily responsible for nutrient absorption. When excessive bacteria compete for these nutrients and produce byproducts through fermentation, it can lead to systemic issues beyond digestive discomfort. Vitamin deficiencies—particularly B12, iron, and fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K)—may develop over time, contributing to fatigue, neurological symptoms, and immune dysfunction. Additionally, the bacterial overgrowth can damage the intestinal lining, potentially increasing intestinal permeability (sometimes called "leaky gut"), which may trigger inflammatory responses throughout the body.

The cyclical nature of SIBO presents a significant challenge for many patients. Without addressing underlying causes, recurrence rates remain high—studies suggest between 40-60% of patients experience symptom return within one year of successful treatment. This highlights the importance of comprehensive management approaches that not only eliminate bacterial overgrowth but also address contributing factors like motility disorders, structural abnormalities, or immune dysfunction.

The SIBO Breath Test Explained

The SIBO breath test is a non-invasive diagnostic tool that measures gas production in the small intestine. The test works on a simple principle: when certain carbohydrates reach bacteria in the small intestine, they ferment and produce gases like hydrogen and methane that are eventually exhaled through the lungs.

During the test, patients consume a solution containing lactulose or glucose after fasting overnight. Breath samples are collected at regular intervals over 2-3 hours. Elevated levels of hydrogen, methane, or hydrogen sulfide in these samples indicate bacterial fermentation occurring in the small intestine—a hallmark of SIBO. The pattern and timing of gas production help clinicians determine not only if SIBO is present but also its severity and location within the small intestine.

Interpreting SIBO Test Results

SIBO breath test results require careful interpretation by healthcare providers. A positive result typically shows an early rise in hydrogen or methane levels, indicating fermentation occurring prematurely in the small intestine rather than in the colon where it normally takes place. Different gas patterns can also indicate different types of SIBO—hydrogen-dominant, methane-dominant, or hydrogen sulfide-dominant—each potentially requiring different treatment approaches.

It's worth noting that false positives and negatives can occur. Factors like recent antibiotic use, improper test preparation, or certain medical conditions can influence results. This is why proper preparation, including following a specific low-fermentation diet before the test, is essential for accurate results.

Understanding H. Pylori

Helicobacter pylori is a spiral-shaped bacterium that colonizes the stomach lining and duodenum (first part of the small intestine). Unlike SIBO, which involves an overgrowth of various bacteria, H. pylori infection specifically involves this single bacterial species. H. pylori has evolved to survive in the harsh acidic environment of the stomach by producing enzymes that neutralize stomach acid in its immediate vicinity.

H. pylori infection is extremely common worldwide, with prevalence rates exceeding 50% in some populations. Many infected individuals remain asymptomatic, but the bacterium can cause chronic gastritis, peptic ulcers, and is recognized as a significant risk factor for gastric cancer. The infection typically spreads through person-to-person contact or consumption of contaminated food or water.

H. Pylori Testing Methods

Several methods exist for detecting H. pylori infection, each with distinct advantages and limitations. The most common tests include:

The Urea Breath Test is similar in concept to the SIBO breath test but works differently. Patients consume a solution containing urea labeled with carbon isotopes. If H. pylori is present in the stomach, its urease enzyme breaks down the urea, releasing labeled carbon dioxide that can be detected in breath samples. This test is highly accurate and non-invasive, making it a preferred option for initial diagnosis and for confirming eradication after treatment.

Blood tests detect antibodies against H. pylori, indicating current or past infection. While convenient, these tests cannot distinguish between active infection and past exposure, limiting their usefulness for confirming successful treatment. Stool antigen tests directly detect H. pylori proteins in stool samples, providing a non-invasive option that accurately identifies active infection. Finally, endoscopic biopsy—though invasive—remains the gold standard, allowing direct visualization of the stomach lining and collection of tissue samples for histological examination and culture.

Accuracy and Reliability Considerations

The accuracy of H. pylori tests varies based on several factors. Recent use of proton pump inhibitors, antibiotics, or bismuth compounds can suppress H. pylori and lead to false-negative results. For this reason, these medications should typically be discontinued for 2-4 weeks before testing. Additionally, the prevalence of H. pylori in the local population affects the predictive value of tests, with positive results being more reliable in high-prevalence regions.

Key Differences Between SIBO and H. Pylori Tests

While both SIBO and H. pylori tests involve detecting bacterial presence in the digestive system, they differ significantly in what they're looking for and how they work. The SIBO breath test measures bacterial fermentation activity throughout the small intestine, detecting an overgrowth of various bacterial species. In contrast, H. pylori tests specifically target a single bacterial species primarily affecting the stomach and duodenum.

The preparation requirements also differ substantially. SIBO testing typically requires a more restrictive preparation diet, avoiding fermentable foods for 24-48 hours before the test and fasting for 12 hours. H. pylori testing generally has less stringent dietary restrictions but may require longer periods off certain medications like antibiotics and acid suppressants.

When to Consider Each Test

Healthcare providers typically recommend a SIBO breath test when patients present with symptoms like chronic bloating, gas, abdominal distension, diarrhea, or constipation—especially when these symptoms persist despite other treatments. SIBO testing is particularly relevant for patients with IBS, inflammatory bowel disease, or those who have undergone abdominal surgeries.

H. pylori testing, on the other hand, is usually considered when patients experience upper abdominal pain, nausea, unexplained weight loss, or symptoms of peptic ulcer disease. It's also recommended for individuals with a family history of gastric cancer or those from high-prevalence regions. In some cases, both tests may be warranted if symptoms overlap or don't clearly point to one condition over the other.

Managing Digestive Symptoms While Awaiting Diagnosis

The period between experiencing digestive symptoms and receiving a definitive diagnosis can be challenging. During this time, several strategies can help manage discomfort while awaiting test results and treatment recommendations. Dietary modifications often provide significant relief for many patients, regardless of whether they have SIBO or H. pylori.

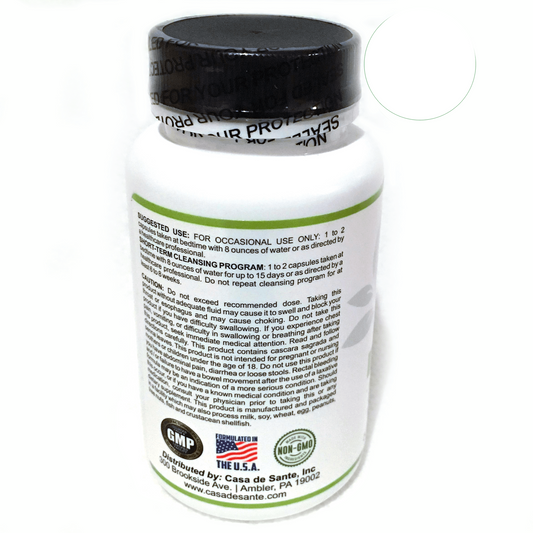

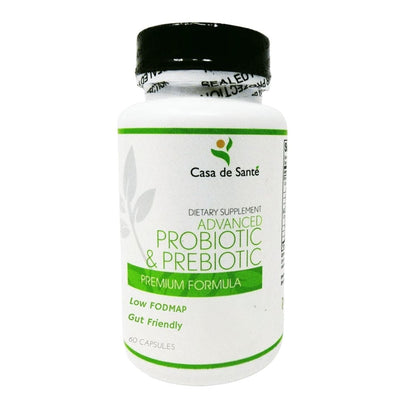

For those suspecting SIBO, a low-FODMAP diet may help reduce fermentation and associated symptoms. This approach limits fermentable carbohydrates that feed bacteria in the small intestine. Similarly, those with suspected H. pylori might benefit from avoiding spicy foods, alcohol, and acidic foods that can irritate the stomach lining.

Supportive Supplements for Digestive Comfort

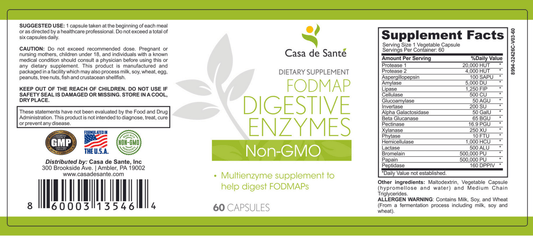

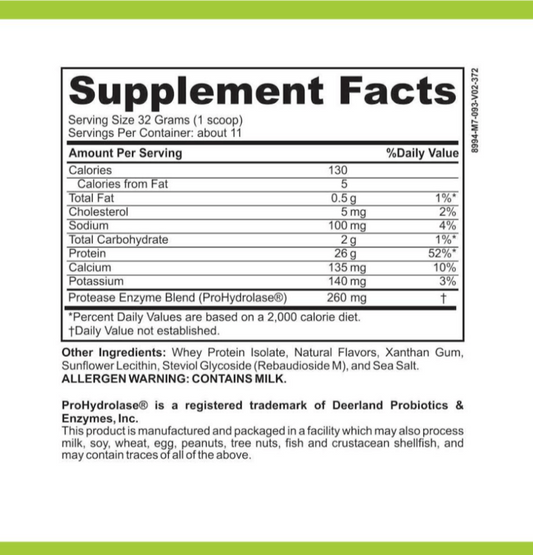

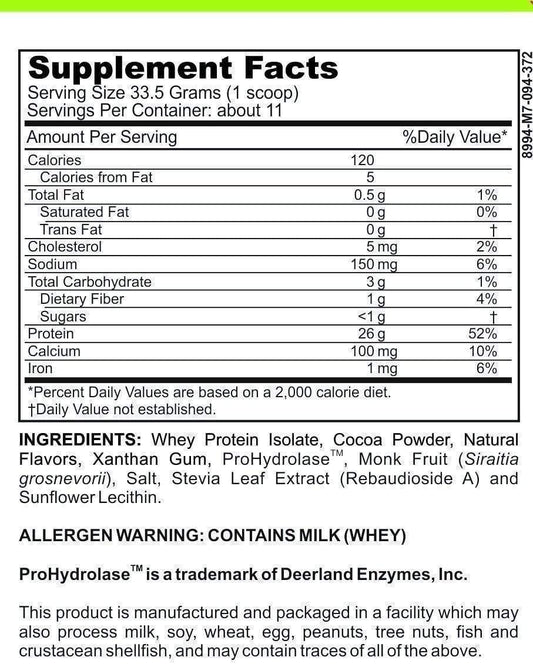

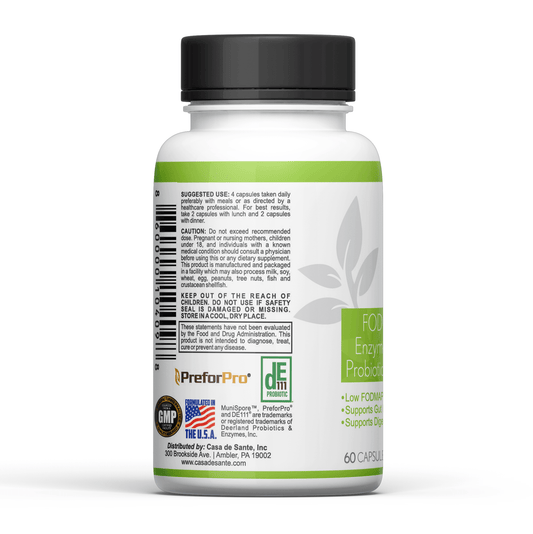

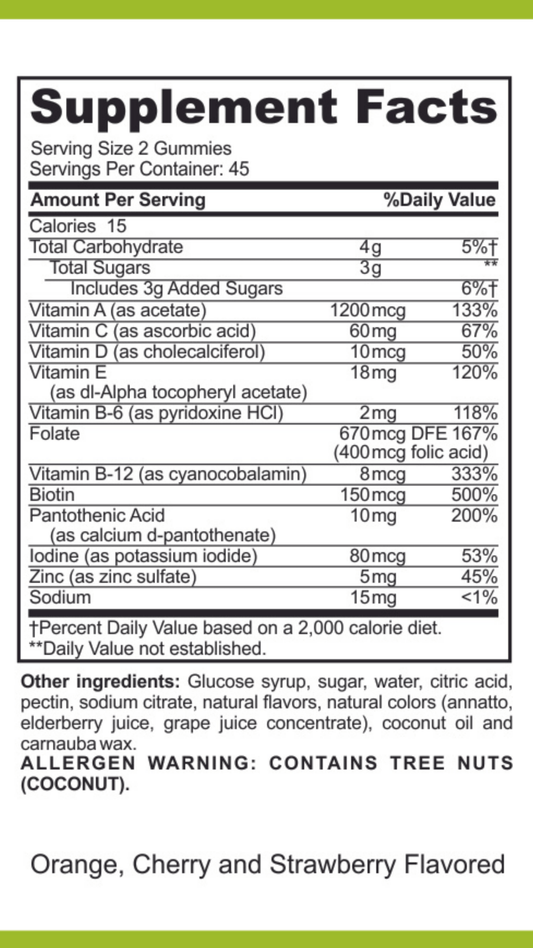

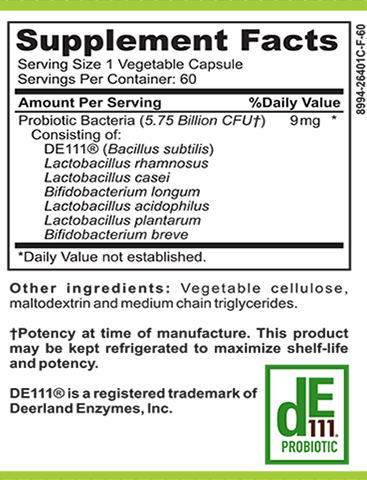

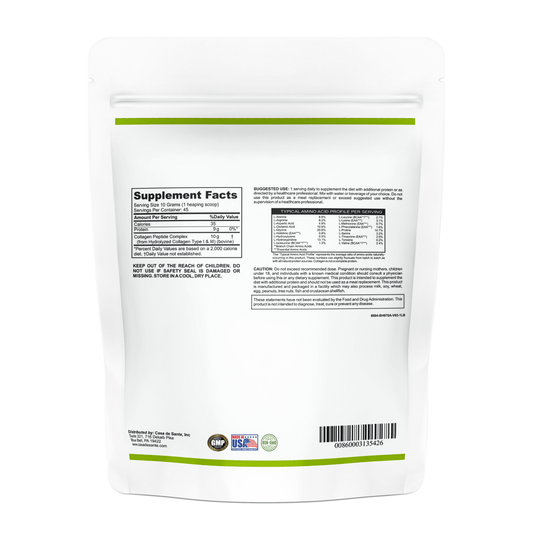

Digestive enzyme supplements can provide meaningful support while awaiting diagnosis and treatment. Professional-grade enzyme complexes like Casa de Sante's low FODMAP certified digestive enzymes offer comprehensive support for those with sensitive digestive systems. Their formula includes 18 targeted enzymes that work synergistically to break down proteins, carbohydrates, fats, and fiber—making nutrients more bioavailable while reducing digestive stress.

These enzymes are particularly beneficial for FODMAP-sensitive individuals, as they include alpha-galactosidase for FODMAP support and lactase for dairy digestion. The dual protease complex (24,000 HUT total) along with bromelain and papain helps break down proteins thoroughly, while lipase (1,250 FIP) optimizes fat digestion. For those experiencing digestive discomfort from either SIBO or H. pylori, such enzyme support can help manage symptoms during the diagnostic process.

Lifestyle Considerations

Beyond diet and supplements, certain lifestyle adjustments can help manage digestive discomfort. Stress management techniques like meditation, yoga, or deep breathing exercises can reduce gut reactivity. Regular, moderate exercise promotes healthy gut motility, which is particularly important for those with SIBO. Adequate hydration and eating smaller, more frequent meals can also ease digestive burden regardless of the underlying condition.

Treatment Approaches Following Diagnosis

Once a diagnosis is confirmed, treatment approaches differ significantly between SIBO and H. pylori. SIBO treatment typically involves a multi-faceted approach, beginning with antibiotics like rifaximin to reduce bacterial overgrowth. This is often followed by a prokinetic agent to improve intestinal motility and prevent recurrence. Dietary modifications, including a low-FODMAP or specific carbohydrate diet, play a crucial role in managing symptoms and preventing relapse.

H. pylori treatment, by contrast, follows more standardized protocols involving combination therapy. The most common approach is triple therapy, which includes two antibiotics (usually clarithromycin and amoxicillin or metronidazole) plus a proton pump inhibitor for 10-14 days. Alternative regimens include quadruple therapy or sequential therapy for regions with high antibiotic resistance. Follow-up testing to confirm eradication is typically performed at least four weeks after completing treatment.

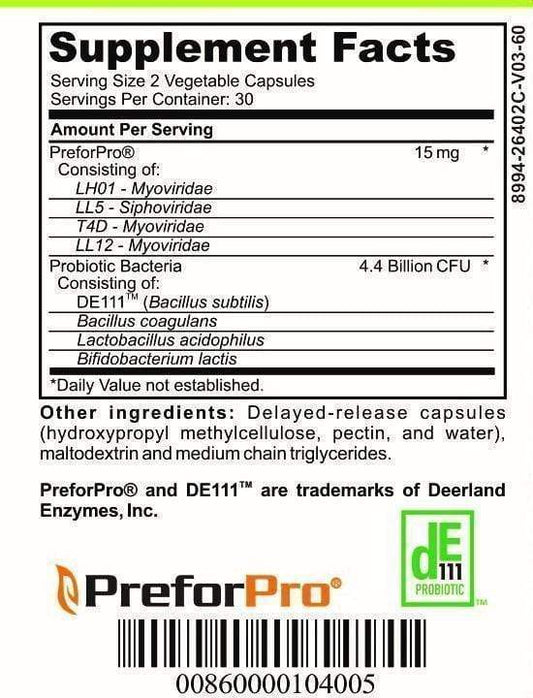

In both conditions, supporting digestive health during and after treatment is essential. High-quality digestive enzymes can help optimize nutrient absorption and reduce digestive stress during the recovery period. For those with persistent symptoms even after successful treatment, ongoing support with targeted enzyme supplements may provide significant quality of life improvements by enhancing digestive efficiency and comfort.