Is SIBO And H. Pylori The Same

Is SIBO And H. Pylori The Same

SIBO and H. pylori are two separate gastrointestinal conditions, each with its own distinct characteristics and effects on the body. While they may both impact the digestive system, they differ in terms of symptoms, causes, diagnosis, and treatment. Understanding these differences is crucial for effective management and improved digestive health.

Understanding SIBO and H. Pylori

Defining SIBO: Symptoms and Causes

Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) refers to a condition where an excessive amount of bacteria accumulates in the small intestine. This overgrowth can disrupt the normal digestive process, leading to a range of symptoms. Common symptoms of SIBO include bloating, abdominal pain, diarrhea, constipation, and malabsorption of nutrients.

SIBO can be a complex condition with various underlying causes. One of the main causes is impaired gut motility, which refers to the movement of food through the digestive system. When gut motility is compromised, it can lead to a buildup of bacteria in the small intestine. This impaired motility can occur due to intestinal adhesions, which are bands of scar tissue that form between abdominal tissues and organs. Additionally, disorders like irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) can also contribute to SIBO by affecting gut motility.

Structural abnormalities in the small intestine can also play a role in the development of SIBO. These abnormalities can include strictures, which are narrowed sections of the intestine, or diverticula, which are small pouches that form in the intestinal wall. These structural issues can create stagnant areas where bacteria can thrive and multiply.

Furthermore, certain medications can increase the risk of SIBO. For example, long-term use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), which are commonly prescribed for acid reflux and ulcers, can alter the balance of bacteria in the gut and contribute to SIBO. Similarly, the use of antibiotics can disrupt the natural gut flora, allowing harmful bacteria to overgrow in the small intestine.

Poor dietary habits can also be a contributing factor to SIBO. Diets high in refined carbohydrates, sugars, and processed foods can provide an abundant food source for bacteria, allowing them to multiply and thrive in the small intestine. Additionally, a lack of dietary fiber can impair gut motility and contribute to the development of SIBO.

Lastly, underlying health conditions can increase the risk of SIBO. Conditions such as diabetes, Crohn's disease, and celiac disease can affect the normal functioning of the digestive system, making individuals more susceptible to SIBO.

Defining H. Pylori: Symptoms and Causes

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a type of bacteria that can infect the stomach lining. This bacterial infection is the leading cause of peptic ulcers and chronic gastritis. The symptoms of H. pylori infection can vary but often include abdominal pain, nausea, bloating, frequent burping, and in some cases, unexplained weight loss.

The primary cause of H. pylori infection is the transmission of the bacterium from person to person. It is primarily spread through contact with contaminated food, water, or utensils. Poor hygiene practices, such as not washing hands properly after using the restroom or before handling food, can contribute to the spread of H. pylori. Living in crowded areas with limited access to clean water and sanitation facilities can also increase the risk of infection.

In addition to transmission through person-to-person contact, H. pylori can also be acquired through the consumption of contaminated food or water. This can occur when food or water is contaminated with H. pylori-infected fecal matter. Improperly cooked food, particularly seafood and shellfish, can be a source of H. pylori infection.

Furthermore, certain risk factors can increase the likelihood of H. pylori infection. Individuals with a compromised immune system, such as those with HIV/AIDS or undergoing chemotherapy, are more susceptible to H. pylori. Additionally, smoking has been found to increase the risk of H. pylori infection, as it can weaken the stomach's protective lining and make it more susceptible to bacterial colonization.

It is important to note that while H. pylori infection is a common cause of peptic ulcers and chronic gastritis, not all individuals infected with H. pylori will develop these conditions. The development of ulcers and gastritis depends on various factors, including the strain of H. pylori, the individual's immune response, and other environmental and lifestyle factors.

The Biological Differences Between SIBO and H. Pylori

The Bacterial Role in SIBO

In SIBO, the bacterial overgrowth occurs primarily in the small intestine, which is not designed to harbor large populations of bacteria. The excessive bacteria can interfere with the normal digestion and absorption processes, leading to nutritional deficiencies and other gastrointestinal symptoms.

Furthermore, SIBO is often associated with a disruption in gut motility, which allows bacteria to migrate from the colon to the small intestine. This migration can result in the accumulation of bacteria in the wrong location, contributing to the development of SIBO.

When bacteria overgrow in the small intestine, they can ferment undigested carbohydrates, producing excessive amounts of gas. This gas can lead to bloating, abdominal distension, and discomfort. Additionally, the presence of bacteria in the small intestine can interfere with the absorption of nutrients, such as vitamins and minerals, leading to deficiencies.

Moreover, the overgrowth of bacteria in the small intestine can trigger an inflammatory response in the gut, further exacerbating the symptoms experienced by individuals with SIBO. This inflammation can damage the lining of the small intestine, impairing its ability to absorb nutrients properly.

The Bacterial Role in H. Pylori

Unlike SIBO, which involves overgrowth of bacteria in the small intestine, H. pylori specifically infects the stomach lining. The bacterium possesses specific mechanisms that enable it to survive in the acidic environment of the stomach, ultimately leading to inflammation and damage to the digestive tissues.

H. pylori infection involves the colonization of the stomach mucosa, where the bacterium produces certain compounds that allow it to evade the host's immune response. This ability to persist in the stomach for prolonged periods leads to the development of ulcers and can increase the risk of certain types of stomach cancer.

When H. pylori colonizes the stomach lining, it triggers an immune response from the body. The immune cells release inflammatory substances to combat the infection, but this response can also damage the surrounding tissues. Over time, chronic inflammation caused by H. pylori can lead to the formation of ulcers in the stomach lining.

In addition to ulcers, H. pylori infection is also associated with an increased risk of gastric cancer. The bacterium produces toxins that can damage the DNA of the stomach cells, increasing the likelihood of cancerous mutations. Furthermore, H. pylori can interfere with the regulation of cell growth and division, further contributing to the development of cancer.

Diagnosis of SIBO and H. Pylori

Diagnostic Tests for SIBO

The diagnosis of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) involves various tests, including breath tests and bacterial cultures. These tests play a crucial role in identifying and confirming the presence of SIBO, allowing healthcare providers to develop an effective treatment plan.

One of the commonly used tests for SIBO is the breath test. This test measures the levels of hydrogen and methane gases produced by bacteria in the small intestine. Patients are required to consume a specific solution containing lactulose or glucose, which is then fermented by the bacteria in the small intestine. As a result, hydrogen and methane gases are released and can be detected in the breath samples collected at regular intervals. Elevated levels of these gases can indicate the presence of SIBO.

In addition to breath tests, healthcare providers may also perform bacterial cultures of small intestinal aspirates. This involves collecting a sample of fluid from the small intestine and analyzing it in a laboratory. Bacterial cultures provide a direct identification of the bacteria present in the small intestine, allowing for a more accurate diagnosis of SIBO.

However, it's important to note that the diagnosis of SIBO is not solely based on these tests. Healthcare providers also take into consideration a patient's medical history, symptoms, and response to treatment. This comprehensive approach ensures that the diagnosis is accurate and tailored to the individual patient.

Diagnostic Tests for H. Pylori

The diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection, a common cause of gastric ulcers and gastritis, is commonly done through a combination of non-invasive tests. These tests are designed to detect the presence of specific compounds or antibodies associated with H. pylori in the body.

One of the non-invasive tests used for diagnosing H. pylori is the breath test. This test involves the patient consuming a solution containing urea, which is broken down by the H. pylori bacteria in the stomach. As a result, carbon dioxide is produced, which can be detected in the breath samples collected at specific intervals. The presence of carbon dioxide indicates the presence of H. pylori infection.

Another non-invasive test is the stool test, which involves collecting a sample of stool and analyzing it for the presence of H. pylori antigens or genetic material. This test is particularly useful in children and individuals who are unable to undergo other diagnostic procedures.

In some cases, a blood test may be performed to detect the presence of antibodies against H. pylori. These antibodies are produced by the immune system in response to the infection. A positive blood test result indicates a current or previous H. pylori infection.

However, in certain situations, an endoscopy may be necessary to directly visualize the stomach lining and collect a tissue sample for analysis. During an endoscopy, a thin, flexible tube with a camera at the end is inserted through the mouth and into the stomach. This allows healthcare providers to examine the stomach lining and take biopsies if necessary. The tissue samples are then analyzed in a laboratory to confirm the presence of H. pylori.

It's important to note that eliminating the presence of H. pylori may require confirmatory tests to ensure eradication of the infection. Follow-up tests, such as breath tests or stool tests, may be conducted after treatment to ensure that the bacteria have been successfully eradicated.

Treatment Options for SIBO and H. Pylori

Treating SIBO: Medications and Lifestyle Changes

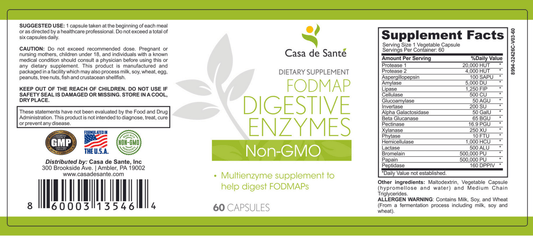

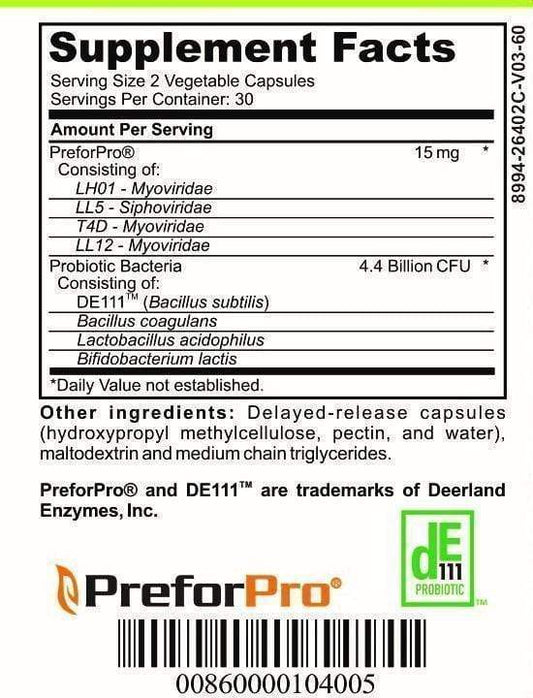

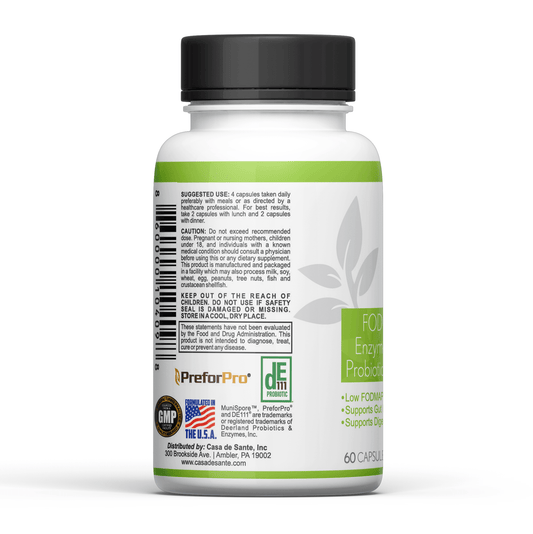

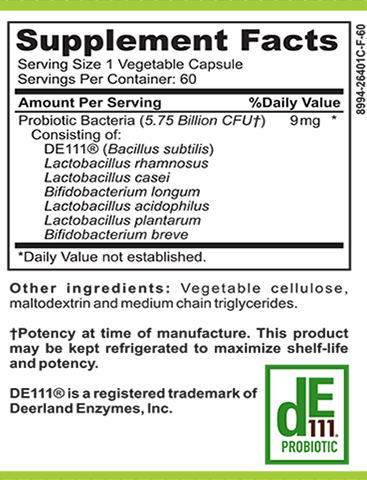

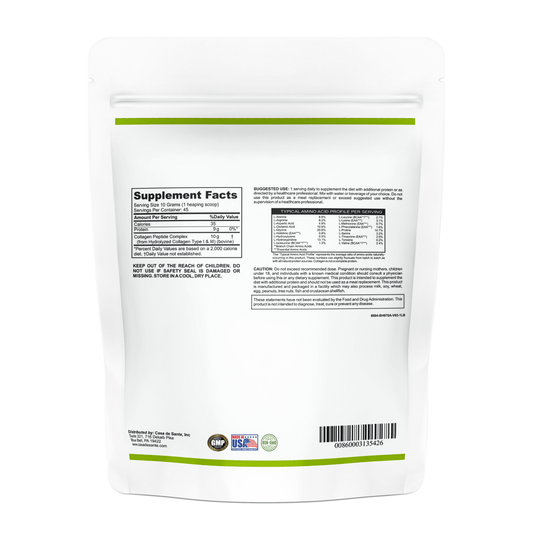

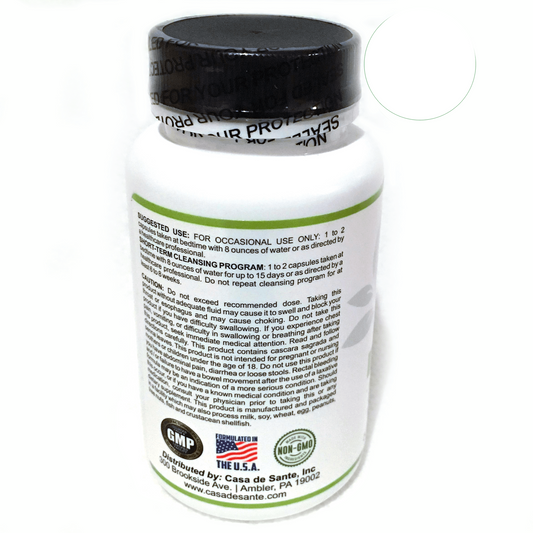

Treating SIBO often involves a combination of antibiotics and dietary modifications. Antibiotics are prescribed to eliminate the overgrowth of bacteria in the small intestine, while dietary changes aim to reduce the intake of fermentable carbohydrates that can encourage bacterial growth. Probiotics and prokinetic agents may also be used to restore normal gut function and improve symptoms.

Additionally, managing any underlying conditions that contribute to SIBO, such as IBS or intestinal adhesions, is an important aspect of treatment. This may require specific medical interventions tailored to the individual's needs.

Treating H. Pylori: Medications and Lifestyle Changes

The treatment of H. pylori infection typically involves a combination of antibiotics and acid-suppressing medications. The antibiotics are used to eradicate the bacterium, while acid-suppressing medications help create a favorable environment for healing the stomach lining. Compliance with the prescribed regimen is essential to ensure successful eradication of H. pylori.

After H. pylori eradication, lifestyle changes such as improving hygiene practices and avoiding the consumption of contaminated food or water can help reduce the risk of reinfection and support long-term digestive health.

The Impact of SIBO and H. Pylori on Digestive Health

How SIBO Affects the Digestive System

SIBO can have widespread effects on the digestive system, leading to nutrient malabsorption, intestinal inflammation, and an imbalance in the gut microbiota. These disruptions can result in chronic diarrhea or constipation, nutritional deficiencies, and increased intestinal permeability. Addressing SIBO is crucial for improving overall digestive health and can lead to relief of associated symptoms.

How H. Pylori Affects the Digestive System

H. pylori infection interrupts the normal functioning of the digestive system, primarily by inducing inflammation in the stomach lining. This inflammation can lead to the development of gastric ulcers and, in some cases, contribute to the development of stomach cancer. Long-term effects may include impaired nutrient absorption and potential nutrient deficiencies. Timely detection and treatment of H. pylori infection are essential to prevent complications and maintain digestive well-being.

Although SIBO and H. pylori share the characteristic of affecting the digestive system, their distinct symptoms, causes, diagnosis, and treatment approaches set them apart. Seeking medical consultation, proper testing, and individualized treatment plans are essential steps towards resolving these conditions and achieving optimal digestive health.