What Causes FODMAP Intolerance in People Without SIBO?

What Causes FODMAP Intolerance in People Without SIBO?

FODMAP intolerance is a condition that affects a significant number of individuals, causing digestive discomfort and various symptoms. While it is commonly associated with Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO), there are cases where people experience FODMAP intolerance without a concurrent SIBO diagnosis. Understanding the causes of FODMAP intolerance in these individuals requires exploring the nature of FODMAPs, the connection between FODMAP intolerance and SIBO, as well as potential factors that contribute to FODMAP intolerance without SIBO.

Understanding FODMAP Intolerance

Defining FODMAPs

FODMAPs, which stands for Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides, and Polyols, are a group of carbohydrates that are commonly found in diverse food sources. These carbohydrates have a unique structure that makes them difficult for some individuals to digest. Instead of being absorbed in the small intestine, they reach the large intestine and are fermented by gut bacteria, causing excessive gas production and triggering various symptoms associated with FODMAP intolerance.

Let's delve deeper into the different types of FODMAPs:

1. Fermentable Oligosaccharides: Oligosaccharides are carbohydrates made up of a small number of sugar molecules linked together. Examples of fermentable oligosaccharides include fructans and galacto-oligosaccharides. Fructans are found in foods such as wheat, rye, onions, and garlic, while galacto-oligosaccharides are present in legumes and certain dairy products.

2. Disaccharides: Disaccharides are carbohydrates composed of two sugar molecules. Lactose, a type of disaccharide, is commonly found in milk and dairy products. Individuals with FODMAP intolerance may have difficulty digesting lactose due to a deficiency in the enzyme lactase, which is responsible for breaking down lactose.

3. Monosaccharides: Monosaccharides are simple sugars that cannot be further broken down into smaller sugar molecules. The monosaccharide associated with FODMAP intolerance is excess fructose. Excess fructose can be found in fruits such as apples, pears, and mangoes, as well as in honey and agave syrup.

4. Polyols: Polyols, also known as sugar alcohols, are carbohydrates that have a sweet taste but are poorly absorbed by the body. Examples of polyols include sorbitol, mannitol, and xylitol. These can be found in certain fruits, such as peaches, plums, and cherries, as well as in sugar-free gum and candies.

Symptoms of FODMAP Intolerance

FODMAP intolerance can present with a range of symptoms, including abdominal pain, bloating, excessive gas, diarrhea, and constipation. These symptoms can significantly impact an individual's quality of life and may vary in intensity and frequency from person to person. It is important to note that these symptoms can also be indicative of other digestive conditions, making accurate diagnosis and understanding the root cause crucial for appropriate management.

Let's explore the symptoms of FODMAP intolerance in more detail:

1. Abdominal Pain: One of the most common symptoms experienced by individuals with FODMAP intolerance is abdominal pain. This pain can range from mild discomfort to severe cramping and can be localized in different areas of the abdomen.

2. Bloating: Bloating is another prevalent symptom associated with FODMAP intolerance. It is characterized by a feeling of fullness and tightness in the abdomen, often accompanied by visible distension.

3. Excessive Gas: Excessive gas production is a result of the fermentation of undigested FODMAPs by gut bacteria. This can lead to increased flatulence, belching, and a feeling of gassiness.

4. Diarrhea: Some individuals with FODMAP intolerance may experience episodes of diarrhea. This can be characterized by loose, watery stools and an increased frequency of bowel movements.

5. Constipation: On the other hand, FODMAP intolerance can also lead to constipation in certain individuals. Constipation is characterized by difficulty passing stools, infrequent bowel movements, and a feeling of incomplete evacuation.

It is important to consult with a healthcare professional if you suspect you may have FODMAP intolerance. They can help you navigate the complexities of the low FODMAP diet and provide appropriate guidance for managing your symptoms.

The Connection Between FODMAP Intolerance and SIBO

What is SIBO?

Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) is a condition characterized by the presence of an abnormally high number of bacteria in the small intestine. These bacteria can produce excessive amounts of gas when they ferment undigested carbohydrates, including FODMAPs, leading to symptoms similar to those experienced in FODMAP intolerance.

SIBO is a complex and often misunderstood condition. It can cause a wide range of symptoms, including bloating, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and malabsorption of nutrients. The overgrowth of bacteria in the small intestine can disrupt the normal digestive process and lead to various health issues.

There are several risk factors that can contribute to the development of SIBO. These include a history of gastrointestinal surgery, certain medications like proton pump inhibitors and antibiotics, and underlying conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and celiac disease.

How SIBO Relates to FODMAP Intolerance

There is a strong association between FODMAP intolerance and SIBO. Research suggests that SIBO can contribute to FODMAP intolerance by altering the balance of gut bacteria and impairing the digestion and absorption of FODMAPs in the small intestine. In individuals without SIBO, however, the causes of FODMAP intolerance are more complex and multifactorial.

When there is an overgrowth of bacteria in the small intestine, the fermentation of undigested carbohydrates, such as FODMAPs, can produce excessive amounts of gas. This can lead to bloating, abdominal discomfort, and other symptoms commonly associated with FODMAP intolerance.

Furthermore, the presence of SIBO can disrupt the normal functioning of the small intestine, impairing its ability to properly digest and absorb FODMAPs. This can result in an accumulation of undigested FODMAPs in the gut, leading to increased fermentation and the production of gas.

It is important to note that while SIBO can contribute to FODMAP intolerance, not all individuals with FODMAP intolerance have SIBO. Other factors, such as genetic predisposition, gut motility issues, and alterations in the gut microbiota, can also play a role in the development of FODMAP intolerance.

Managing both SIBO and FODMAP intolerance often involves a comprehensive approach that includes dietary modifications, antimicrobial therapy to address the bacterial overgrowth in SIBO, and addressing any underlying conditions that may be contributing to the development of these conditions.

By understanding the connection between FODMAP intolerance and SIBO, healthcare professionals can better tailor treatment plans to address the root causes of these conditions and provide relief for individuals experiencing gastrointestinal symptoms.

Potential Causes of FODMAP Intolerance Without SIBO

Genetic Factors

Genetic factors may play a role in the development of FODMAP intolerance. Some individuals may have genetic variations that affect the production or function of enzymes responsible for breaking down and absorbing FODMAPs. This impaired ability to digest FODMAPs can lead to their fermentation in the large intestine and subsequent symptoms of FODMAP intolerance.

Research has shown that certain genetic variations, such as mutations in the lactase gene, can result in reduced lactase production. This can lead to lactose intolerance, which is a type of FODMAP intolerance. Similarly, variations in genes involved in the metabolism of fructose, such as the aldolase B gene, can contribute to fructose malabsorption, another form of FODMAP intolerance.

Furthermore, studies have identified other genetic factors that may influence FODMAP intolerance. For example, variations in genes related to the production of enzymes like sucrase-isomaltase and alpha-galactosidase have been associated with difficulties in digesting certain FODMAPs, such as fructans and galacto-oligosaccharides.

Dietary Habits

Dietary habits also contribute to the development of FODMAP intolerance. Consuming a diet high in FODMAPs can overload the digestive system and increase the likelihood of experiencing symptoms. Certain dietary patterns, such as a high intake of processed foods or a lack of dietary fiber, may be associated with an increased risk of FODMAP intolerance in individuals without SIBO.

Processed foods, which are often high in additives and preservatives, can contain significant amounts of FODMAPs. These additives, such as high fructose corn syrup or inulin, can be difficult to digest for individuals with FODMAP intolerance. Additionally, a diet lacking in dietary fiber can contribute to FODMAP intolerance as fiber plays a crucial role in promoting healthy digestion and preventing the fermentation of FODMAPs in the gut.

It is important to note that dietary habits can vary greatly among individuals, and what may trigger symptoms in one person may not affect another. Keeping a food diary and working with a registered dietitian can help identify specific dietary triggers and develop a personalized approach to managing FODMAP intolerance.

Gut Health and Microbiome

The health and diversity of the gut microbiome play a crucial role in the digestion and fermentation of FODMAPs. Disruptions in the gut microbiome, which can result from factors such as antibiotic use, chronic stress, or a history of gastrointestinal infections, may contribute to FODMAP intolerance. These disruptions can alter the balance of gut bacteria and impair the ability to digest FODMAPs effectively.

Antibiotics, while important for treating bacterial infections, can also have unintended consequences on the gut microbiome. They can disrupt the natural balance of bacteria, potentially leading to an overgrowth of certain species that produce excess gas during the fermentation of FODMAPs. Chronic stress, which can affect gut motility and increase sensitivity to digestive symptoms, has also been linked to alterations in the gut microbiome and FODMAP intolerance.

Furthermore, individuals with a history of gastrointestinal infections, such as food poisoning or gastroenteritis, may experience long-term changes in their gut microbiome. These changes can impact the ability to properly digest FODMAPs and contribute to the development of FODMAP intolerance.

Understanding the complex relationship between the gut microbiome and FODMAP intolerance is an area of ongoing research. Strategies aimed at restoring and maintaining a healthy gut microbiome, such as probiotic supplementation or dietary interventions, may hold promise for managing FODMAP intolerance in the absence of SIBO.

Diagnosis and Testing for FODMAP Intolerance

Common Diagnostic Tools

The diagnosis of FODMAP intolerance typically involves a comprehensive assessment of medical history, symptoms, and dietary patterns. Additionally, healthcare providers may recommend specific diagnostic tests, such as a breath test, to measure the levels of hydrogen and methane gas produced during the fermentation of FODMAPs. These tests can aid in confirming FODMAP intolerance and ruling out other possible causes of symptoms.

Understanding Test Results

Interpreting test results for FODMAP intolerance can be complex. Healthcare providers with expertise in digestive disorders can help patients understand their test results and provide guidance on appropriate management strategies. It is essential to work closely with a healthcare professional to ensure accurate diagnosis and effective treatment.

Managing FODMAP Intolerance Without SIBO

Dietary Modifications

The cornerstone of managing FODMAP intolerance without SIBO is implementing dietary modifications. A low-FODMAP diet, which involves limiting the intake of high-FODMAP foods and gradually reintroducing them to identify individual triggers, is commonly recommended. Working with a registered dietitian who specializes in digestive health can be invaluable in tailoring a suitable dietary plan that ensures nutritional adequacy while reducing symptoms.

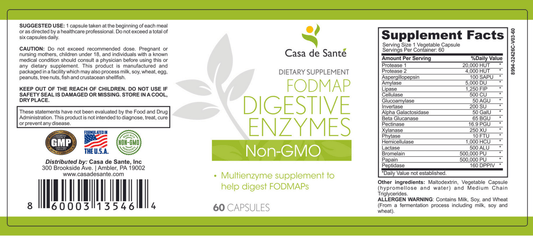

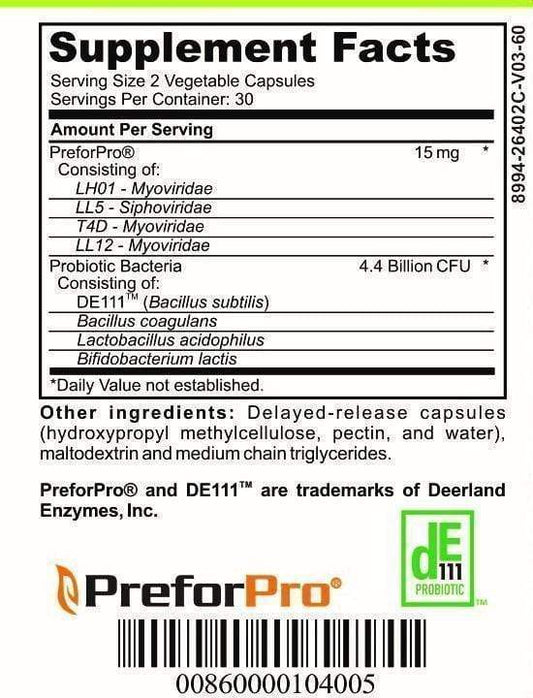

Medication and Supplements

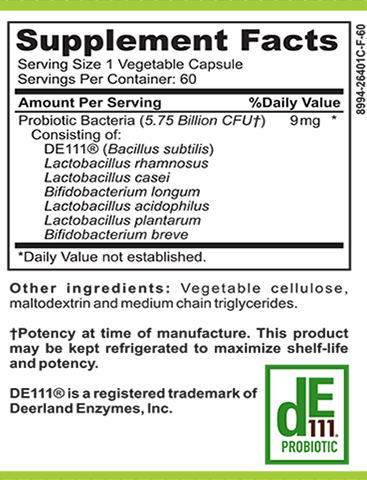

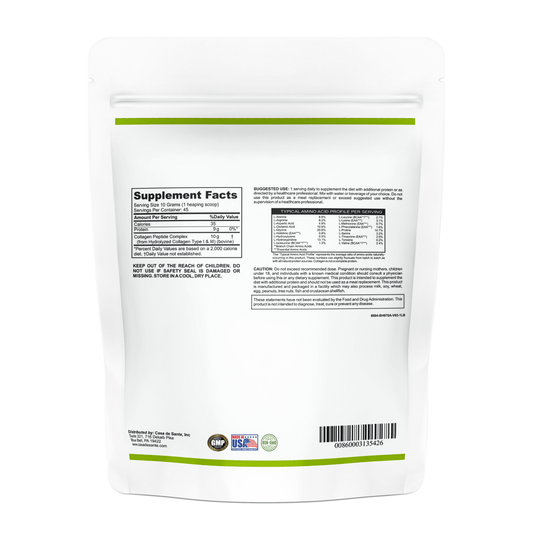

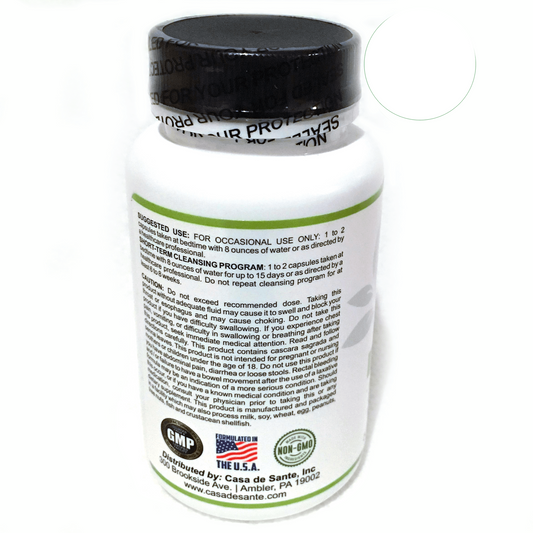

In some cases, healthcare providers may recommend the use of medications or supplements to manage symptoms associated with FODMAP intolerance. For example, certain medications can help alleviate pain or regulate bowel movements. Probiotics, which are beneficial bacteria, may also be suggested to support gut health and rebalance the gut microbiome.

Lifestyle Changes

Lifestyle changes can complement dietary modifications in managing FODMAP intolerance. Incorporating stress management techniques, regular physical activity, and adequate sleep can help improve digestive health and reduce symptom severity. Additionally, mindful eating practices, such as chewing food thoroughly and eating at a relaxed pace, may aid in symptom management.

In conclusion, while FODMAP intolerance without SIBO presents its unique challenges, understanding the causes of this condition can guide effective management strategies. Genetic factors, dietary habits, and gut health all contribute to the development of FODMAP intolerance in individuals without SIBO. Accurate diagnosis, through proper testing and consultation with healthcare professionals, is crucial for tailored treatment plans that incorporate dietary modifications, medications, and lifestyle changes. By addressing the underlying causes, individuals can regain control over their digestive health and improve their overall well-being.