Probiotics Play a Crucial Role in Gut Health

As studies continue to emerge, research supports probiotics and their crucial role in gut health, especially for those diagnosed with gastrointestinal (GI) disorders. This article will discuss the research that supports the potential benefits of certain strains of healthy bacteria to the GI tract.

What is the Gut Microbiome?

Within the gastrointestinal tract of each human being, trillions of microorganisms and bacteria make up the gut microbiota or gut microbiome. Each person has a balance within their microbiome that originates early in life. However, certain factors, such as diet and medications, can alter and disrupt the balance in the gut microbiome, called dysbiosis. Dysbiosis can lead to susceptibility to infection or disease as the gut microbiome can not as easily fight off pathogens as they enter the GI tract. Additionally, GI symptoms, such as diarrhea can occur, when healthy bacteria in the gut are missing.

There are three known mechanisms of action through which probiotics can improve overall human health. These mechanisms are described as follows (Segers & Lebeer, 2014):

- Healthy bacteria that are present in probiotics can inhibit the invasion of harmful bacteria and pathogens that cause sickness

- Certain probiotics can increase immune system functioning through increased mucus production, for example

- Probiotic strains can improve the immune response through their method of action, based on which strain is present

Probiotics can help maintain a healthy balance by providing, or replenishing, common strains very similar to the bacteria already present in the GI tract.

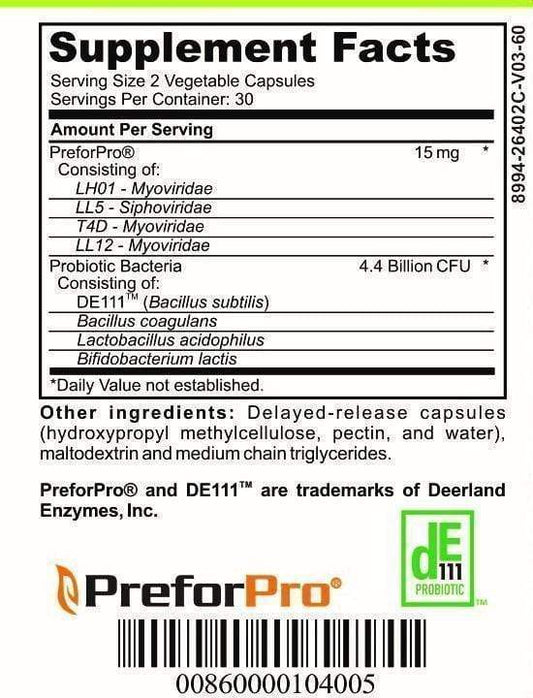

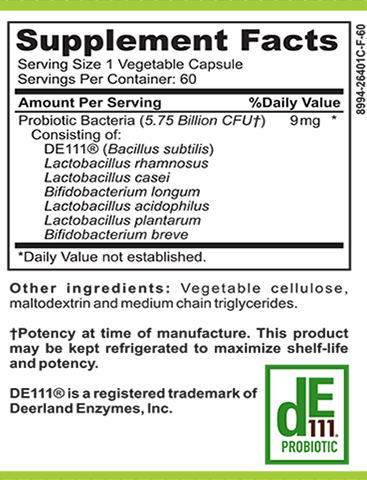

What Types of Bacteria are Common in Probiotics?

The bacterial strain Bacillus subtilis, or B. subtilis, is known for its immune-boosting benefits, especially in the elderly (Lefevre et al., 2016). B. subtilis has been thoroughly tested for safety, whether in food or supplement form and is safe for healthy individuals.

Lactobacillus rhamnosus, or L. rhamnosus, is another prevalent strain of bacteria used in probiotics. The benefits of L. rhamnosus have been well researched due to its unique ability to adhere well to the intestinal mucus of the digestive tract (Segers & Lebeer, 2014). L. rhamnosus has the potential to prevent and potentially treat GI infections and diarrhea. However, more placebo-controlled experimental studies need to be carried out to solidify these findings and learn more about the mechanism behind the benefits of L. rhamnosus. The safety of L. rhamnosus has been confirmed through many clinical trials as participants did not experience any adverse effects from being administered the strain.

Another member of the lactobacillus family is Lactobacillus casei or L. casei. When your gut microbiome lacks healthy bacteria, the consumption of L. casei can help restore balance in the gut, called symbiosis. The primary function of L. casei is preventing diarrhea, including traveler’s diarrhea and diarrhea related to antibiotic use (Pietrangelo, 2017).

Moving on to Bifidobacterium longum or B. longum. This bacteria is most commonly found living in the large intestine, or colon, of the GI tract. Part of the bifidobacteria family, B. longum colonizes in the gut early in life and is present for years. However, the amount present eventually starts to decrease over time. Besides stabilizing the gut microbiome, many randomized controlled trials involving B. longum have shown it also decreases constipation as well as boosts the body's immune system (Wong, Odamaki, & Xiao, 2019; Tennis, 2021).

Lactobacillus acidophilus or L. acidophilus produces lactic acid through the breakdown of carbohydrates, such as lactose found in milk (Poulson, Horowitz, & Trevino, n.d.). Most L. acidophilus is grown in milk or foods made from milk. When certain medications and antibiotics are used, the normal flora in the gut microbiome is often disrupted and killed. Now, L. acidophilus comes in to replace the good bacteria, often relieving diarrhea.

Next is Lactobacillus plantarum, or L. plantarum. This bacterial strain is often used in functional foods, meaning they are nutrient-rich with many health benefits (Behera, Ray, & Zdolec, 2018). Additionally, in a double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial, 214 participants with IBS were recruited for a four-week experiment (Ducrotte, Sawant, & Jayanthi, 2012). The results showed that pain severity, pain frequency, and bloating were significantly lower in the group that received L. plantarum than those that received a placebo capsule.

Finally, there is a bacteria called Bifidobacterium breve, or B. breve. Studies have shown that B. breve supplementation is associated with decreased constipation and may improve the overall health of the digestive tract (Duncombe, n.d.). Clinical trials continue to determine the effects of B. breve on alleviation of symptoms in IBS patients.

In all, probiotics, and all of the bacteria they contain, play a crucial role in gut health and in supporting a healthy and happy gut microbiome.

References:

Behera, S. S., Ray, R. C., & Zdolec, N. (2018, May 28). lactobacillus plantarum with functional properties: An approach to increase safety and shelf-life of fermented foods. BioMed research international. Retrieved May 13, 2022, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5994577/

Bifidobacterium breve. Consumer's Health Report. (n.d.). Retrieved May 13, 2022, from https://www.consumershealthreport.com/probiotic-supplements/bifidobacterium-breve/

Ducrotté, P., Sawant, P., & Jayanthi, V. (2012, August 14). Clinical trial: Lactobacillus plantarum 299V (DSM 9843) improves symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. World journal of gastroenterology. Retrieved May 13, 2022, from https:/www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3419998/

Lactobacillus acidophilus. Lactobacillus Acidophilus - Health Encyclopedia - University of Rochester Medical Center. (n.d.). Retrieved May 13, 2022, from https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/encyclopedia/content.aspx?contenttypeid=19&contentid=Lactobacillus

Lefevre, M., Racedo, S. M., Denayrolles, M., Ripert, G., Desfougères, T., Lobach, A. R., Simon, R., Pélerin, F., Jüsten, P., & Urdaci, M. C. (2016, November 5). Safety assessment of bacillus subtilis CU1 for use as a probiotic in humans. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. Retrieved May 13, 2022, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0273230016303452

Pietrangelo, A. (2017, March 21). Lactobacillus casei: Benefits, side effects, and more. Healthline. Retrieved May 13, 2022, from https://www.healthline.com/health/digestive-health/lactobacillus-casei

Segers, M. E., & Lebeer, S. (2014, August 29). Towards a better understanding of lactobacillus rhamnosus GG--host interactions. Microbial cell factories. Retrieved May 13, 2022, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4155824/

Tannis, A. (2021, April 19). Bifidobacterium Longum. International Probiotics Association. Retrieved May 13, 2022, from https://internationalprobiotics.org/bifidobacterium-longum/

Wong, C. B., Odamaki, T., & Xiao, J.-zhong. (2019, February 8). Beneficial effects of Bifidobacterium longum subsp. longum BB536 on human health: Modulation of gut microbiome as the principal action. Journal of Functional Foods. Retrieved May 13, 2022, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1756464619300684