What High Methane Levels Mean for Your Health and Environment

What High Methane Levels Mean for Your Health and Environment

Methane is a powerful greenhouse gas that often flies under the radar in environmental discussions, yet its impact on both our planet and our personal health is significant. From digestive issues to global climate concerns, understanding methane's role can help us make better choices for our wellbeing and the environment. This article explores the implications of elevated methane levels, their sources, and practical solutions to address them.

Understanding Methane: The Basics

Methane (CH₄) is a colorless, odorless gas that occurs both naturally and through human activities. While carbon dioxide often dominates climate change conversations, methane actually has a warming potential approximately 25 times greater than CO₂ over a 100-year period, making it a potent contributor to global warming despite its shorter atmospheric lifespan.

In the human body, methane can be produced by certain microorganisms in the digestive tract. These methanogens thrive in oxygen-free environments and convert hydrogen and carbon dioxide into methane gas. While some methane production is normal, excessive levels can indicate digestive imbalances and contribute to uncomfortable symptoms.

Common Sources of Methane

Environmental methane comes from diverse sources including natural wetlands, agriculture (particularly livestock), fossil fuel extraction, landfills, and wastewater treatment. Ruminant animals like cattle and sheep produce significant amounts through their digestive processes, while rice paddies create ideal conditions for methane-producing bacteria in their flooded fields.

In humans, methane production primarily occurs in the large intestine. Approximately 30-60% of healthy individuals have methane-producing gut microbes, with varying levels of gas production. Diet, gut microbiome composition, and digestive health all influence how much methane your body produces.

The chemical structure of methane is deceptively simple—a single carbon atom bonded to four hydrogen atoms in a tetrahedral arrangement. This molecular simplicity belies its complex environmental impact. When released into the atmosphere, methane interacts with hydroxyl radicals, which serve as the atmosphere's primary cleansing mechanism. This interaction leads to methane's relatively short atmospheric lifetime of approximately 12 years, compared to carbon dioxide's centuries-long persistence. However, during this brief atmospheric residence, methane's efficiency at trapping heat makes it particularly concerning for short-term climate forcing effects.

Historically, atmospheric methane concentrations remained relatively stable for thousands of years until the Industrial Revolution, when levels began rising dramatically. Ice core samples from Greenland and Antarctica reveal that pre-industrial methane concentrations hovered around 700 parts per billion (ppb), whereas today's measurements exceed 1,900 ppb—a staggering increase of more than 150%. This rapid rise correlates strongly with human activities, particularly the expansion of agriculture, fossil fuel exploitation, and waste management practices that create ideal conditions for methane generation and release.

Methane and Digestive Health

Elevated methane levels in the digestive system have been linked to several gastrointestinal conditions. When methane gas builds up in the intestines, it can slow gut transit time—the speed at which food moves through your digestive tract—potentially leading to constipation and other digestive discomforts.

Research has shown connections between high intestinal methane production and conditions like irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C), small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), and inflammatory bowel diseases. These conditions can significantly impact quality of life and require targeted approaches for management.

Signs of Methane-Related Digestive Issues

If you're experiencing chronic constipation, bloating, abdominal discomfort, or excessive gas, elevated methane levels might be contributing to your symptoms. These issues often occur because methane gas can slow intestinal motility by up to 59%, creating a sluggish digestive system that struggles to move waste efficiently through the colon.

Many people with methane-dominant digestive issues also report feeling uncomfortably full after eating small amounts of food, experiencing incomplete bowel movements, or dealing with alternating constipation and diarrhea. These symptoms can be particularly challenging for those with FODMAP sensitivities, as certain fermentable carbohydrates may further increase gas production.

Testing for Methane Imbalances

Healthcare providers can measure methane levels through breath testing, which detects gases produced by intestinal bacteria. These non-invasive tests typically involve consuming a sugar solution and then measuring the gases in your breath at regular intervals. Elevated methane readings may indicate conditions like methane-dominant SIBO or other digestive imbalances that require treatment.

While breath testing isn't perfect, it provides valuable information about your digestive function and can guide treatment decisions. If you suspect methane-related digestive issues, consulting with a gastroenterologist or functional medicine practitioner familiar with these conditions is recommended.

Environmental Impact of Methane

Beyond personal health, methane emissions pose significant environmental challenges. As the second most abundant anthropogenic greenhouse gas after carbon dioxide, methane contributes approximately 20% of global warming effects. Its concentration in the atmosphere has more than doubled since pre-industrial times, largely due to human activities.

What makes methane particularly concerning is its efficiency at trapping heat. While it remains in the atmosphere for less time than CO₂ (about 12 years compared to centuries), its warming impact is far more intense during that period. This makes reducing methane emissions a potentially high-impact strategy for slowing climate change in the near term.

Methane Hotspots and Monitoring

Scientists track methane emissions through satellite technology, ground-based monitoring stations, and aircraft measurements. These efforts have identified concerning "methane hotspots" around the world, often associated with oil and gas production, large-scale livestock operations, and major landfills. Understanding these emission patterns helps target reduction efforts where they'll have the greatest impact.

Recent technological advances have improved our ability to detect and quantify methane leaks, particularly from industrial sources. This enhanced monitoring capability is driving more accurate emissions inventories and supporting accountability for major emitters.

Managing Methane for Better Health

For those dealing with methane-dominant digestive issues, several approaches can help restore balance and improve symptoms. Dietary modifications often form the foundation of treatment, with particular attention to reducing foods that feed methane-producing bacteria while supporting overall gut health.

Many healthcare providers recommend a temporary low-FODMAP diet to reduce fermentable carbohydrates that can feed problematic gut bacteria. This approach has shown significant benefits for many people with IBS and SIBO, though it's typically used as a short-term intervention rather than a permanent solution.

Digestive Enzyme Support

Supplementing with high-quality digestive enzymes can be a game-changer for those with methane-related digestive issues. These specialized proteins help break down food components more completely, reducing the amount of undigested material available to feed methane-producing bacteria in the gut.

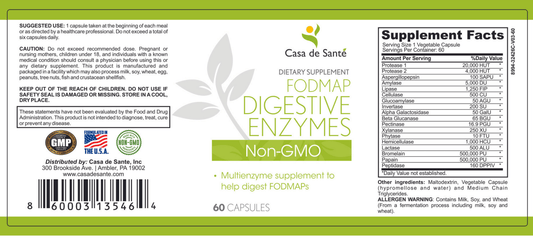

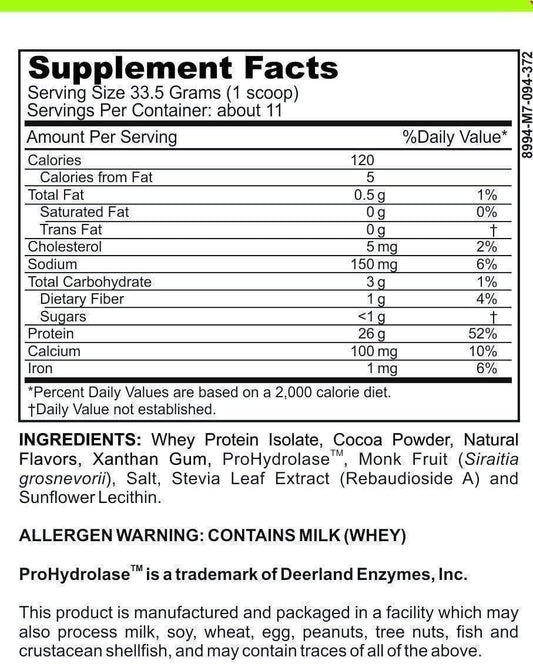

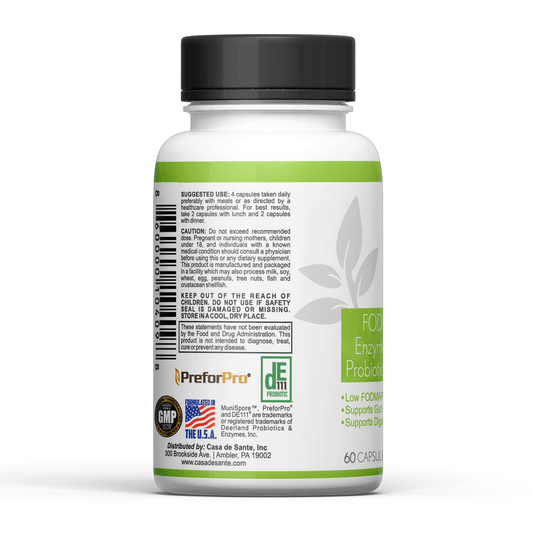

Products like Casa de Sante's low FODMAP certified digestive enzymes offer comprehensive support with their professional-grade enzyme complex. With 18 targeted enzymes including dual protease complexes, alpha-galactosidase for FODMAP support, and lipase for fat breakdown, these supplements can significantly improve digestive comfort while enhancing nutrient absorption. For those with sensitive digestive systems, this gentle yet powerful formula provides the enzymatic support needed to reduce bloating and discomfort associated with high methane production.

Antimicrobial Approaches

In cases of confirmed methane-dominant SIBO, healthcare providers may prescribe antimicrobial treatments to reduce problematic bacteria. These might include prescription antibiotics like rifaximin and neomycin, or herbal antimicrobials such as oregano oil, berberine, and neem. These treatments aim to reduce the population of methane-producing organisms and restore a healthier microbial balance.

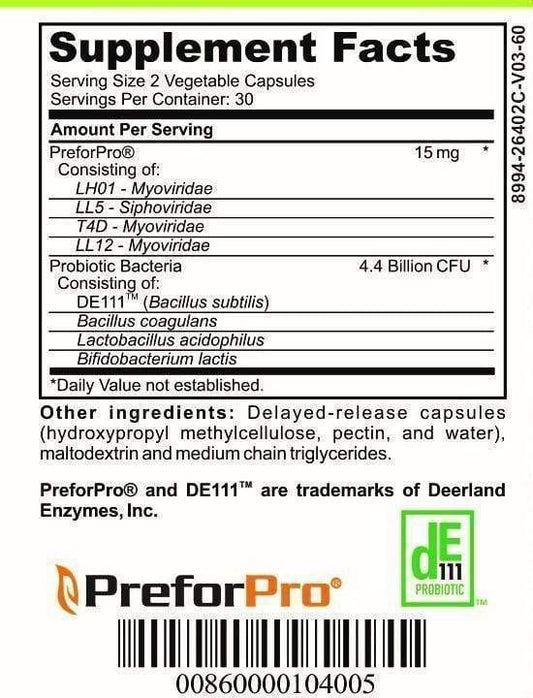

Following antimicrobial treatment, a carefully planned reintroduction of beneficial bacteria through probiotics and prebiotic foods helps establish a healthier gut ecosystem less prone to methane overproduction. This approach recognizes that the goal isn't to eliminate all bacteria but rather to foster a diverse and balanced microbiome.

Reducing Methane's Environmental Footprint

On the environmental front, numerous strategies exist to reduce methane emissions across sectors. In agriculture, improved livestock feed formulations can reduce enteric fermentation, while better manure management practices capture and utilize methane rather than releasing it. Alternative rice cultivation methods that reduce flooding periods can significantly cut emissions from rice production.

The energy sector has substantial opportunities to reduce methane leakage throughout the natural gas supply chain. Regular monitoring and maintenance of pipelines, storage facilities, and distribution systems can prevent losses that harm both the environment and company profits. Some companies are implementing advanced leak detection technologies and committing to rapid repair protocols.

Personal Actions That Make a Difference

Individual choices also impact methane emissions. Reducing food waste prevents organic material from decomposing in landfills and releasing methane. Composting food scraps aerobically (with oxygen) produces primarily carbon dioxide rather than methane, making it a better option for unavoidable food waste.

Dietary choices influence methane production both environmentally and internally. Plant-forward diets generally have lower methane footprints than those heavy in ruminant animal products. Interestingly, these same dietary patterns often support healthier gut function with less methane production in the digestive tract—a win-win for personal and planetary health.

Conclusion

High methane levels represent a complex challenge with implications for both human health and environmental sustainability. By understanding the sources and impacts of excessive methane, we can make informed choices that benefit our digestive comfort while contributing to climate solutions.

For those struggling with methane-related digestive issues, comprehensive approaches including dietary modifications, targeted supplements like Casa de Sante's enzyme complex, and appropriate medical interventions can provide significant relief. Meanwhile, supporting methane reduction initiatives in agriculture, energy, and waste management helps address the broader environmental concerns.

As research continues to deepen our understanding of methane's role in both bodily systems and global climate, the connections between personal health and planetary wellbeing become increasingly clear. Taking action on methane represents an opportunity to make meaningful improvements on both fronts—a truly holistic approach to some of our most pressing challenges.