Feeling Hungry After Eating: A Common SIBO Symptom?

Feeling Hungry After Eating: A Common SIBO Symptom?

Feeling hungry after eating can be a perplexing and frustrating experience. It goes against the natural order of things - you eat to satisfy your hunger, not to exacerbate it. But for individuals with Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO), this phenomenon is all too familiar. Understanding SIBO and its connection to hunger is essential for managing this condition effectively.

Understanding SIBO: An Overview

SIBO stands for Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth, a condition characterized by an excessive growth of bacteria in the small intestine. Normally, the small intestine only contains a small number of bacteria. However, certain factors can disrupt the delicate balance, allowing bacteria from other parts of the digestive system to colonize the small intestine.

What is SIBO?

SIBO occurs when bacteria from the large intestine migrate to the small intestine and multiply, leading to an overgrowth. This overgrowth disrupts the normal digestive process and can cause various symptoms, including the peculiar sensation of feeling hungry after eating.

Causes and Risk Factors of SIBO

Several factors can contribute to the development of SIBO. These include impaired intestinal motility, anatomical abnormalities or strictures in the small intestine, reduced stomach acid production, and certain medical conditions like diabetes or Crohn's disease. Additionally, the use of medications such as proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) or antibiotics can also increase the risk of SIBO.

The Connection Between SIBO and Hunger

SIBO affects digestion in various ways, ultimately leading to feelings of hunger after eating. Understanding these mechanisms can shed light on why this symptom occurs and help individuals with SIBO manage their condition more effectively.

How SIBO Affects Digestion

The small intestine plays a crucial role in digesting and absorbing nutrients from the food we eat. When bacteria overgrowth occurs in this part of the digestive system, it can impair the natural digestive process. The excess bacteria compete with the body for nutrients, leading to poor nutrient absorption and digestive discomfort.

Furthermore, SIBO can disrupt the normal movement of the small intestine, known as peristalsis. Peristalsis helps propel food through the digestive tract, allowing for efficient digestion and absorption. When SIBO is present, this movement can become sluggish or irregular, further hindering the proper breakdown of food and absorption of nutrients.

In addition to these effects, SIBO can also damage the lining of the small intestine, leading to inflammation and intestinal permeability. This condition, often referred to as leaky gut, allows undigested food particles, toxins, and bacteria to enter the bloodstream. The immune system responds to this invasion by triggering an inflammatory response, which can cause a variety of symptoms, including increased hunger.

Why SIBO Can Make You Feel Hungry After Eating

One plausible explanation for feeling hungry after eating with SIBO is that the excess bacteria in the small intestine ferment carbohydrates, producing gas and causing bloating. This rapid fermentation process not only results in gas accumulation but also stimulates the release of hunger hormones, leading to an increased sensation of hunger even after eating.

Furthermore, SIBO can disrupt the production and function of important digestive enzymes, such as lactase and sucrase. These enzymes are responsible for breaking down lactose and sucrose, respectively. When SIBO impairs their function, the body may struggle to digest certain carbohydrates, leading to increased hunger as the body craves more nutrients.

Moreover, SIBO can alter the balance of gut bacteria, leading to dysbiosis. Dysbiosis refers to an imbalance in the types and quantities of bacteria in the gut. Certain bacteria, when overrepresented, can produce compounds that interfere with appetite regulation, leading to increased feelings of hunger.

Additionally, the inflammation caused by SIBO can disrupt the communication between the gut and the brain. The gut-brain axis is a bidirectional communication system, and disruptions in this connection can lead to dysregulated appetite and hunger signals.

It is important to note that SIBO can also cause malabsorption of certain nutrients, such as vitamin B12 and iron. Deficiencies in these essential nutrients can lead to various symptoms, including increased hunger.

Overall, the connection between SIBO and hunger is multifaceted. The excess bacteria, fermentation processes, impaired digestion, dysbiosis, and inflammation all contribute to the sensation of increased hunger even after eating. Understanding these mechanisms can help individuals with SIBO address their symptoms and develop effective management strategies.

Recognizing Other SIBO Symptoms

Hunger pangs are just one of the many symptoms that individuals with SIBO may experience. Knowing the full range of symptoms can help identify the condition and seek appropriate treatment.

When it comes to SIBO, hunger pangs are often accompanied by a host of other uncomfortable symptoms. These symptoms can vary in severity and may come and go, making it important to recognize the full range of manifestations.

Common Symptoms of SIBO

Aside from feeling hungry after eating, individuals with SIBO often experience abdominal pain or discomfort, bloating, diarrhea, and general malaise. These symptoms can be quite distressing and can significantly impact daily life.

Abdominal pain or discomfort is a common complaint among those with SIBO. This pain is often described as a dull ache or cramping sensation and can occur anywhere in the abdomen. Bloating, another common symptom, is characterized by a feeling of fullness or tightness in the abdomen, often accompanied by visible distention.

Diarrhea is a frequent occurrence in individuals with SIBO. The excess bacteria in the small intestine can interfere with the normal digestion and absorption of nutrients, leading to loose or watery stools. This can further contribute to nutrient deficiencies and weight loss.

General malaise, or a sense of overall discomfort or unease, is also commonly reported by those with SIBO. This feeling of being unwell can be attributed to the body's immune response to the presence of excess bacteria in the small intestine.

Less Common Symptoms of SIBO

In some cases, SIBO can manifest in less typical ways, making the diagnosis more challenging. It is important to be aware of these less common symptoms to ensure a comprehensive understanding of the condition.

Nutrient deficiencies are a potential consequence of SIBO. The overgrowth of bacteria in the small intestine can interfere with the absorption of essential nutrients, such as vitamins, minerals, and fats. This can lead to deficiencies in important nutrients and subsequent health issues.

Weight loss is another less common symptom of SIBO. When the body is unable to properly absorb nutrients due to the presence of excess bacteria, it can result in unintentional weight loss. This can be particularly concerning for individuals who are already underweight or struggling with maintaining a healthy weight.

Vitamin deficiencies can also occur in individuals with SIBO. The disruption of normal nutrient absorption can lead to inadequate levels of vitamins, such as vitamin B12, vitamin D, and vitamin K. These deficiencies can have wide-ranging effects on various bodily functions and overall health.

Fatigue is a commonly reported symptom in individuals with SIBO. The constant battle between the body's immune system and the overgrowth of bacteria can be exhausting, leading to a persistent feeling of tiredness and lack of energy.

Joint pain is another less common symptom that some individuals with SIBO may experience. The exact mechanism behind this symptom is not fully understood, but it is believed to be related to the body's inflammatory response to the presence of excess bacteria in the small intestine.

Diagnosing SIBO

Properly diagnosing Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) is crucial for developing an effective treatment plan and managing hunger pangs. SIBO occurs when there is an excessive growth of bacteria in the small intestine, leading to various digestive symptoms.

When it comes to diagnosing SIBO, your healthcare provider may employ various medical tests to confirm its presence and understand the underlying causes. These tests are essential for accurate diagnosis and guiding treatment decisions.

Medical Tests for SIBO

The gold standard for diagnosing SIBO is the breath test. This test measures the levels of hydrogen and methane gases produced by bacteria in the small intestine. During the test, you will be asked to consume a specific carbohydrate solution, and your breath samples will be collected and analyzed at regular intervals. Elevated levels of hydrogen and methane gases indicate the presence of SIBO.

In addition to the breath test, other tests may also be used to evaluate the overall health of the digestive system. Blood work can provide valuable insights into the functioning of various organs involved in digestion, such as the liver and pancreas. Stool analysis, on the other hand, can help identify any abnormalities in the gut microbiota and assess the presence of inflammation or infection.

Interpreting SIBO Test Results

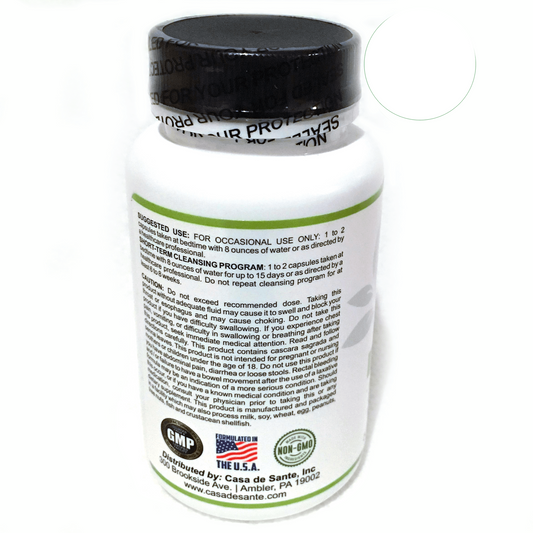

Interpreting SIBO test results requires expert knowledge and clinical experience. It is crucial to consult with a healthcare provider specialized in gut health to understand the significance of test results and determine the appropriate course of action.

A healthcare provider experienced in SIBO can analyze the test results in the context of your symptoms, medical history, and other factors. They can help identify the specific type of bacteria involved, the severity of the overgrowth, and any potential complications that may arise if left untreated.

Based on the test results, your healthcare provider can develop a personalized treatment plan tailored to your specific needs. This may include dietary changes, antimicrobial therapy, and other interventions aimed at rebalancing the gut microbiota and reducing bacterial overgrowth.

Regular follow-up appointments and repeat testing may be necessary to monitor your progress and adjust the treatment plan as needed. It is important to work closely with your healthcare provider to effectively manage SIBO and improve your digestive health.

Treating SIBO and Managing Hunger Pangs

While there is no one-size-fits-all approach to treating SIBO (Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth), several strategies can help manage hunger pangs and reduce symptoms effectively. SIBO is a condition characterized by an overgrowth of bacteria in the small intestine, leading to various digestive issues.

SIBO can cause a range of symptoms, including bloating, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and constipation. In some cases, individuals may also experience hunger pangs shortly after eating, which can be uncomfortable and disruptive to daily life.

Dietary Changes to Manage SIBO

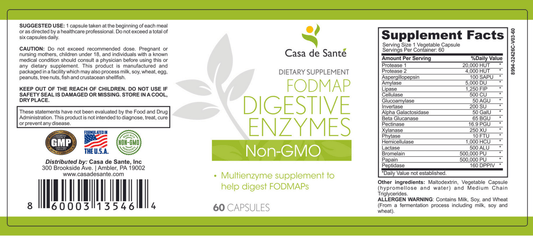

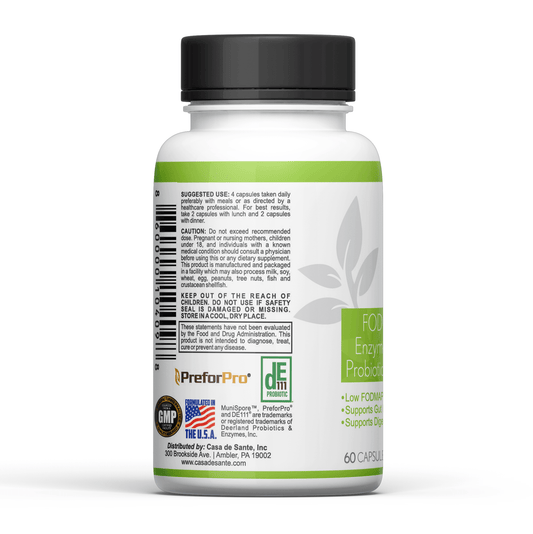

Modifying the diet plays a central role in managing SIBO symptoms, including hunger pangs. A healthcare provider may recommend a specific diet, such as the Low FODMAP (Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides, and Polyols) diet, which limits the consumption of fermentable carbohydrates that feed the bacteria in the small intestine.

The Low FODMAP diet involves avoiding foods high in fermentable carbohydrates, such as certain fruits, vegetables, grains, and dairy products. By reducing the availability of these carbohydrates, the bacteria in the small intestine have less fuel to thrive on, leading to a decrease in symptoms.

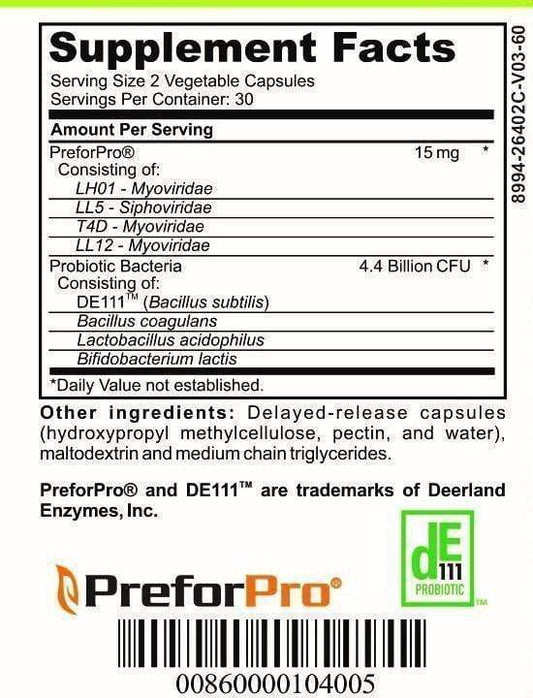

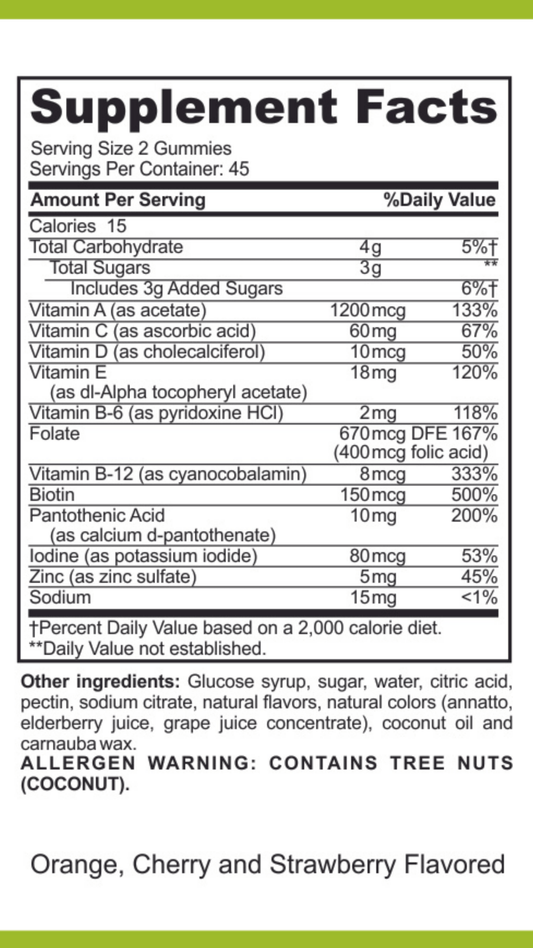

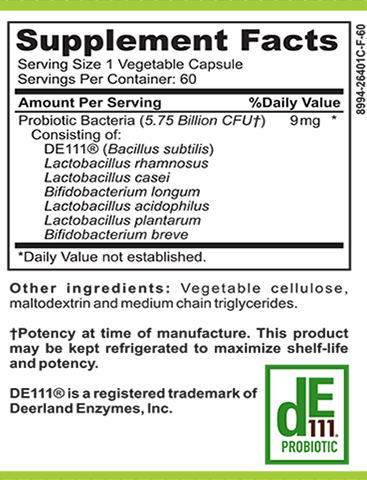

Additionally, incorporating probiotics and prebiotics into the diet may help restore the balance of gut bacteria. Probiotics are beneficial bacteria that can help support a healthy gut environment, while prebiotics are non-digestible fibers that serve as food for these beneficial bacteria.

Probiotics can be found in fermented foods like yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut, and kimchi, while prebiotics are present in foods like garlic, onions, bananas, and asparagus. Including these foods in the diet can help promote a diverse and balanced gut microbiome.

Medications and Supplements for SIBO

In some cases, healthcare providers may prescribe antibiotics to eradicate the excess bacteria in the small intestine. Antibiotics such as rifaximin are commonly used for the treatment of SIBO. These medications work by targeting and killing the bacteria, thereby reducing the overgrowth and alleviating symptoms.

Other medications, such as motility agents or prokinetics, may be used to improve intestinal motility and prevent bacterial overgrowth. Motility agents help stimulate the movement of the digestive tract, facilitating the proper transit of food and preventing stagnation that can contribute to SIBO.

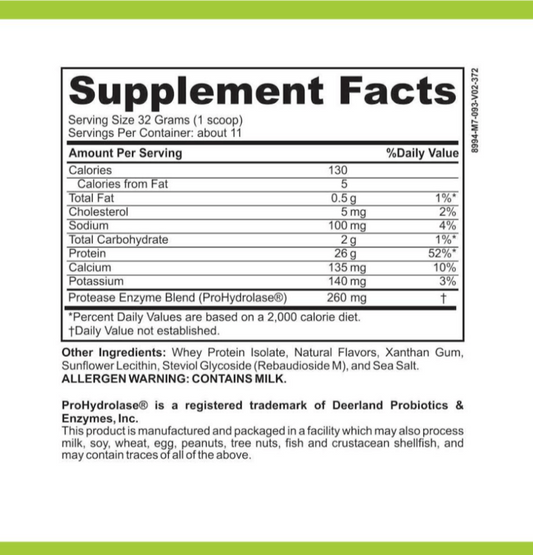

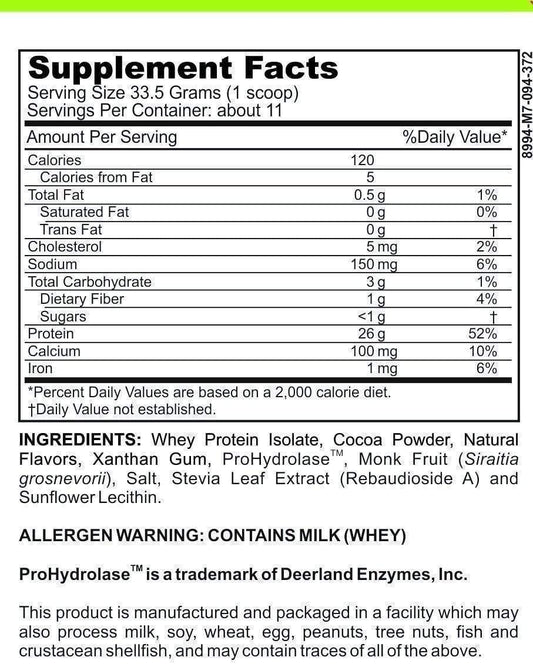

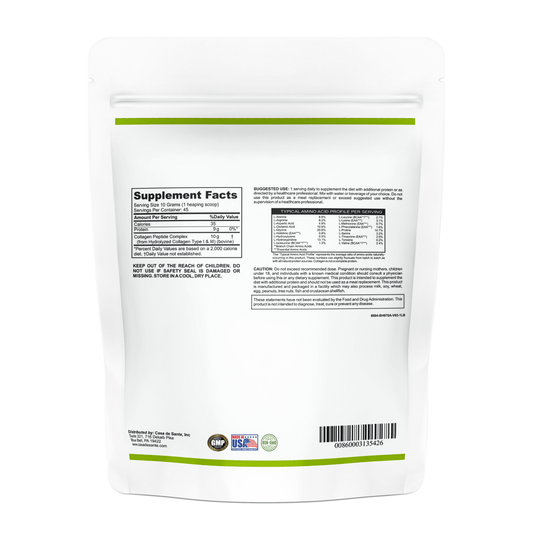

Supplementing with specific nutrients, vitamins, or enzymes may also be recommended to address any deficiencies caused by SIBO. For example, individuals with SIBO may have impaired absorption of certain nutrients, such as vitamin B12 or iron. Supplementing with these nutrients can help correct deficiencies and support overall health.

In conclusion, feeling hungry after eating can be a common symptom of SIBO. Understanding the connection between SIBO and hunger is essential for managing this condition effectively. By recognizing other SIBO symptoms, seeking an accurate diagnosis, and implementing appropriate treatment strategies, individuals can take control of their digestive health and alleviate the discomfort of hunger pangs. It is important to consult with a healthcare provider or a registered dietitian before making any significant dietary or medication changes to ensure the most appropriate and personalized approach to managing SIBO.