Signs And Symptoms Of Lactose Intolerance Causing Bloating

Signs And Symptoms Of Lactose Intolerance Causing Bloating

Understanding Lactose Intolerance

Definition and Overview

Lactose intolerance is a common digestive condition where the body is unable to fully digest lactose, a sugar found primarily in milk and dairy products. This occurs when the small intestine doesn't produce enough of an enzyme called lactase, which is responsible for breaking down lactose into simpler sugars that can be absorbed into the bloodstream.

When lactose moves through the digestive system without being properly broken down, it reaches the colon where bacteria ferment it, producing gases and fluids that cause the uncomfortable symptoms associated with lactose intolerance. This condition affects millions of people worldwide and can significantly impact quality of life if not properly managed.

Symptoms and Effects

The symptoms of lactose intolerance typically appear within 30 minutes to 2 hours after consuming lactose-containing foods or beverages. Bloating is one of the most common and uncomfortable symptoms, characterized by a feeling of fullness, tightness, or swelling in the abdomen. This bloating occurs as bacteria in the colon ferment the undigested lactose, producing excess gas.

Other common symptoms include abdominal pain, cramping, rumbling sounds in the belly (borborygmi), diarrhea, and gas. The severity of symptoms varies from person to person and depends on factors such as the amount of lactose consumed and an individual's level of lactase deficiency. Some people may be able to tolerate small amounts of lactose without experiencing significant discomfort, while others may react to even minimal amounts.

Causes and Types of Lactose Intolerance

Primary Lactose Intolerance

Primary lactose intolerance is the most common form and develops naturally over time. In most mammals, including humans, lactase production decreases after weaning as the body naturally reduces its ability to digest milk. This type of lactose intolerance is genetically determined and often begins to show symptoms during adolescence or early adulthood.

The decline in lactase production is gradual, which explains why many people don't notice symptoms until they're older. Interestingly, some populations, particularly those with a long history of dairy consumption, have evolved to maintain lactase production throughout adulthood, a condition known as lactase persistence.

Secondary Lactose Intolerance

Secondary lactose intolerance occurs when lactase production decreases due to damage to the small intestine. This damage can result from various intestinal conditions such as celiac disease, Crohn's disease, bacterial or viral infections, or other inflammatory bowel diseases. Unlike primary lactose intolerance, the secondary form may be temporary if the underlying condition is treated effectively.

Once the intestinal lining heals, lactase production may return to normal levels, allowing for improved lactose digestion. However, in cases of chronic intestinal damage, secondary lactose intolerance can become a long-term condition requiring ongoing management.

Congenital Lactose Intolerance

Congenital lactose intolerance is an extremely rare form present from birth. In this condition, babies are born with little or no lactase production due to a genetic mutation. Symptoms appear shortly after birth when the infant begins consuming breast milk or formula containing lactose, and include severe diarrhea, dehydration, and failure to gain weight.

This rare genetic disorder requires immediate medical attention and specialized feeding approaches. Fortunately, congenital lactose intolerance is exceptionally uncommon, with only a handful of cases documented in medical literature.

Developmental Lactose Intolerance

Developmental lactose intolerance can occur in premature infants born before 34 weeks gestation. This happens because lactase production typically increases significantly during the third trimester of pregnancy. Premature babies may temporarily have insufficient lactase levels until their digestive systems mature further.

This form of lactose intolerance is usually temporary, resolving as the infant develops. Healthcare providers may recommend specialized feeding approaches until the baby's digestive system matures enough to handle lactose properly.

Risk Factors for Lactose Intolerance

Genetic Predisposition

Genetics play a significant role in determining who develops lactose intolerance. The ability to produce lactase throughout adulthood (lactase persistence) is controlled by a specific gene variant that evolved in populations with a long history of dairy consumption. Without this genetic adaptation, lactase production naturally declines after childhood.

Family history is a strong indicator of risk. If your parents or siblings have lactose intolerance, you're more likely to develop it as well. Genetic testing can sometimes identify predisposition to lactose intolerance, though it's not routinely performed unless there are specific diagnostic concerns.

Age and Ethnic Background

Lactose intolerance becomes more common with age, as lactase production naturally decreases over time in most people. While symptoms can begin in childhood, they more typically emerge during adolescence or adulthood. The condition is particularly prevalent in certain ethnic groups, reflecting evolutionary adaptations to traditional diets.

People of East Asian, West African, Arab, Jewish, Greek, and Italian descent have higher rates of lactose intolerance, with some populations showing prevalence rates of 70-90%. In contrast, populations with long histories of dairy farming and consumption, such as those of Northern European descent, have lower rates, sometimes as low as 5-15%.

Digestive Health History

A history of gastrointestinal issues can increase the risk of developing secondary lactose intolerance. Conditions that damage the small intestine, such as celiac disease, Crohn's disease, or intestinal infections, can reduce lactase production. Treatments like chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or certain medications that affect the digestive tract can also temporarily impair lactase production.

Previous abdominal surgeries, particularly those involving the small intestine, may also increase the risk of lactose intolerance. Monitoring digestive symptoms after such procedures can help identify if lactose intolerance has developed as a complication.

Identifying Lactose Intolerance

Diagnostic Methods

Several diagnostic tests can help confirm lactose intolerance. The hydrogen breath test is the most common and measures the amount of hydrogen in your breath after consuming lactose. Normally, little hydrogen is detectable in breath, but undigested lactose leads to increased hydrogen production by gut bacteria, which can then be measured.

Other diagnostic approaches include the lactose tolerance test, which measures blood sugar levels after consuming lactose (those with lactose intolerance show a smaller rise in blood glucose), and stool acidity tests, which are primarily used for infants and children. In some cases, intestinal biopsies may be performed to measure lactase levels directly, though this is less common due to its invasive nature.

Symptoms to Monitor

Self-monitoring symptoms can be an effective way to identify potential lactose intolerance. Keep a detailed food diary recording all food and beverages consumed, along with any symptoms that develop afterward. Pay particular attention to the timing of symptoms in relation to dairy consumption – lactose intolerance symptoms typically appear within 30 minutes to 2 hours after ingesting lactose.

Watch for patterns of bloating, abdominal pain, diarrhea, or gas that consistently occur after consuming dairy products. The severity of symptoms often correlates with the amount of lactose consumed, so note whether larger portions of dairy trigger more intense reactions. This information can be valuable when consulting with healthcare providers about a potential diagnosis.

Dietary Adjustments for Lactose Intolerance

Foods High in Lactose

Understanding which foods contain significant amounts of lactose is essential for managing symptoms. Milk and milk-based products are the primary sources, with a cup of milk containing approximately 12-13 grams of lactose. Ice cream, soft cheeses (like cottage cheese and ricotta), and cream-based products also contain substantial amounts.

Less obvious sources include processed foods that contain milk derivatives, such as whey, curds, milk byproducts, dry milk solids, and nonfat dry milk powder. These ingredients are common in bread, cereal, instant potatoes, soups, breakfast drinks, salad dressings, and many processed meats. Reading food labels carefully becomes an important habit for those with lactose intolerance.

Lactose-Free Alternatives

Fortunately, there are numerous lactose-free alternatives available today. Lactose-free milk is regular milk with added lactase enzyme that pre-digests the lactose. Plant-based milk alternatives such as almond, soy, oat, coconut, and rice milk naturally contain no lactose and can be used as substitutes in most recipes and applications.

hard, aged cheeses like cheddar, parmesan, and swiss contain minimal lactose due to the aging process and are often tolerated well. Many dairy companies now offer lactose-free versions of yogurt, ice cream, and other dairy products, making it easier to enjoy favorite foods without discomfort. When shopping, look for products labeled "lactose-free" or that contain added lactase enzyme.

Managing Symptoms of Lactose Intolerance

Dietary and Lifestyle Changes

The most effective approach to managing lactose intolerance is modifying your diet to reduce lactose intake. However, complete elimination of dairy isn't always necessary. Many people with lactose intolerance can tolerate small amounts of lactose, especially when consumed as part of a meal rather than on an empty stomach.

Experimenting with different dairy products can help identify personal tolerance levels. For instance, yogurt with live active cultures is often better tolerated because the bacteria help break down lactose. Introducing small amounts of dairy gradually and increasing portions slowly can sometimes help the body adjust and potentially improve tolerance over time.

Long-Term Management Strategies

For long-term management, maintaining adequate calcium and vitamin D intake is crucial, as these nutrients are abundant in dairy products. Non-dairy sources of calcium include fortified plant milks, leafy greens, almonds, and calcium-set tofu. Vitamin D can be obtained from sunlight exposure, fatty fish, and fortified foods.

Regular monitoring of nutritional status may be beneficial, especially for those who eliminate dairy completely. In some cases, calcium and vitamin D supplements may be recommended by healthcare providers to prevent deficiencies. Developing sustainable dietary habits that avoid trigger foods while ensuring nutritional adequacy is the key to successful long-term management.

Over-the-Counter Solutions

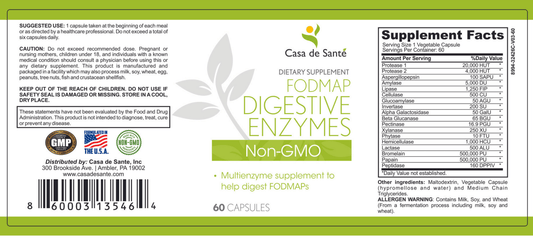

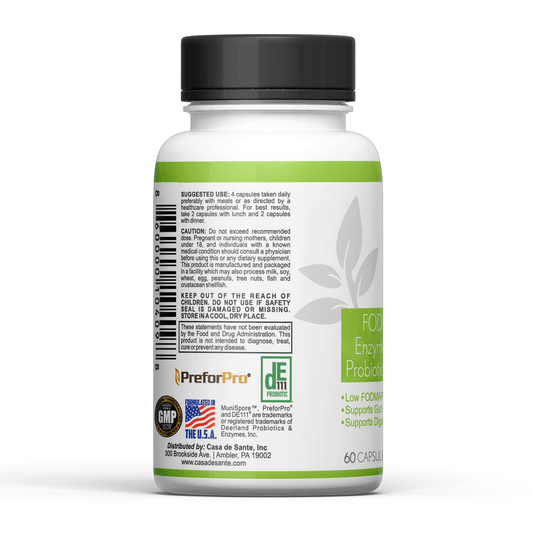

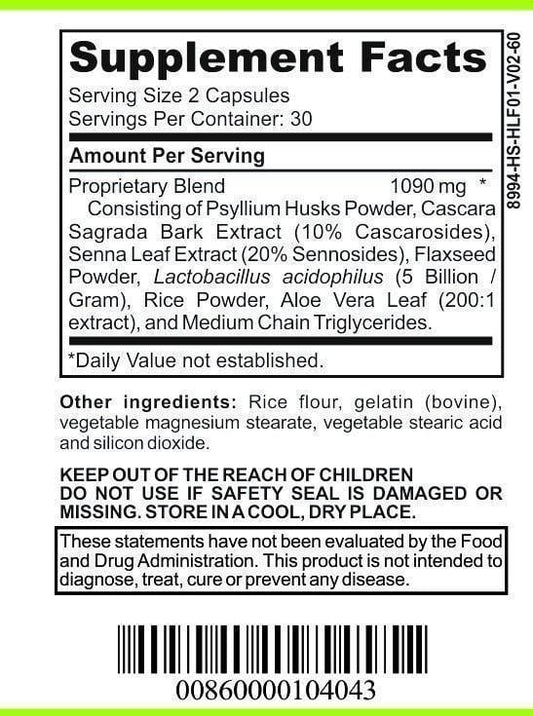

Lactase enzyme supplements, available over-the-counter, can be taken before consuming dairy products to help digest lactose. These supplements, like those found in professional-grade enzyme complexes, provide the lactase enzyme that the body lacks, allowing for improved digestion of lactose-containing foods. For example, products containing 500 ALU of lactase can significantly reduce digestive discomfort when taken at the beginning of meals containing dairy.

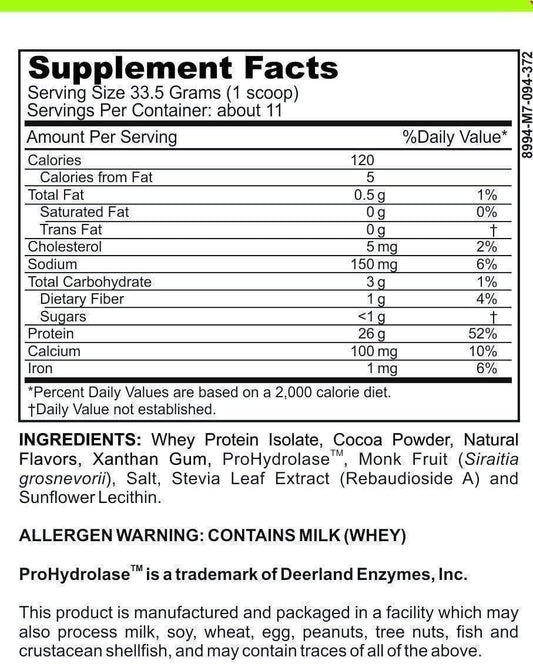

Comprehensive digestive enzyme blends that include lactase along with other enzymes can provide broader support for those who experience multiple food sensitivities. These professional-strength formulations often combine lactase with proteases for protein digestion, amylase for carbohydrate breakdown, and lipase for fat digestion, offering complete digestive support that can be particularly beneficial for those following specialized diets like Paleo or Keto.

Gut Health and Lactose Intolerance

Role of the Gut Microbiome

The gut microbiome plays a significant role in how the body responds to lactose. Some gut bacteria can produce lactase-like enzymes that help break down lactose, potentially reducing symptoms of intolerance. Research suggests that individuals with lactose intolerance may have different gut microbiome compositions compared to those who digest lactose normally.

Factors that affect gut microbiome health, such as antibiotic use, stress, and overall diet, may influence how severely lactose intolerance symptoms manifest. Maintaining a diverse and healthy gut microbiome through a varied plant-based diet rich in fiber can potentially improve lactose tolerance in some individuals.

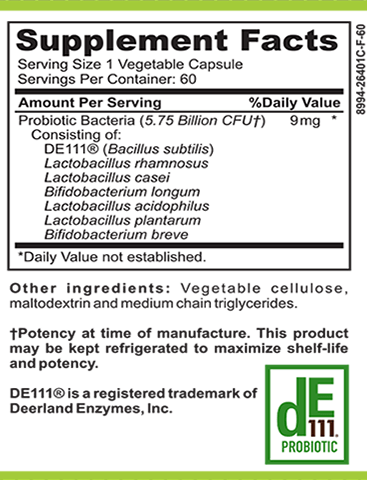

Probiotics and Lactase Supplements

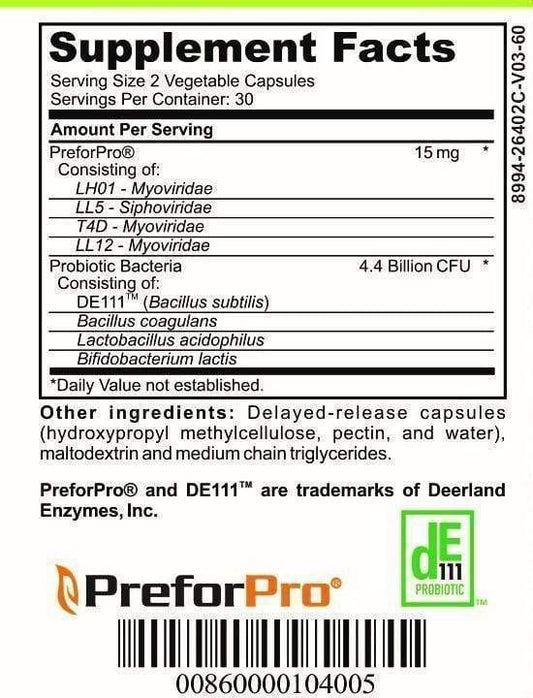

Probiotic supplements containing beneficial bacteria, particularly certain strains of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, may help improve lactose digestion in some people. These bacteria can produce enzymes that break down lactose and may help modify the gut environment to reduce symptoms of intolerance.

When combined with lactase supplements, probiotics may offer a comprehensive approach to managing lactose intolerance. Professional-grade enzyme complexes that include both lactase (typically 500 ALU or more) and other digestive enzymes can provide targeted support for dairy digestion while also addressing other potential digestive challenges. This multi-faceted approach can be particularly beneficial for those with sensitive digestive systems who need complete digestive support beyond just lactose management.