Top 10 Examples of Oligosaccharides in Common Foods

Top 10 Examples of Oligosaccharides in Common Foods

Oligosaccharides might sound like a complex scientific term, but these carbohydrates are actually present in many foods we consume daily. Consisting of 3-10 sugar molecules linked together, oligosaccharides play important roles in our diet and digestive health. While some people may experience digestive discomfort from certain oligosaccharides (especially those with IBS or FODMAP sensitivities), these compounds also function as prebiotics, feeding beneficial gut bacteria and supporting overall digestive wellness.

Understanding which foods contain these compounds can help you make informed dietary choices, whether you're looking to increase your prebiotic intake or manage digestive sensitivities. Let's explore the top 10 common foods rich in oligosaccharides that you might already have in your kitchen.

What Are Oligosaccharides?

Oligosaccharides occupy the middle ground in the carbohydrate family - more complex than simple sugars (monosaccharides and disaccharides) but less complex than polysaccharides like starch. Their unique molecular structure allows them to resist digestion in the upper gastrointestinal tract, instead traveling to the colon where gut bacteria ferment them.

The most common types include fructooligosaccharides (FOS), galactooligosaccharides (GOS), and inulin. These compounds have gained attention in nutrition science for their prebiotic effects and potential health benefits, including improved calcium absorption, reduced inflammation, and enhanced immune function.

The Prebiotic Connection

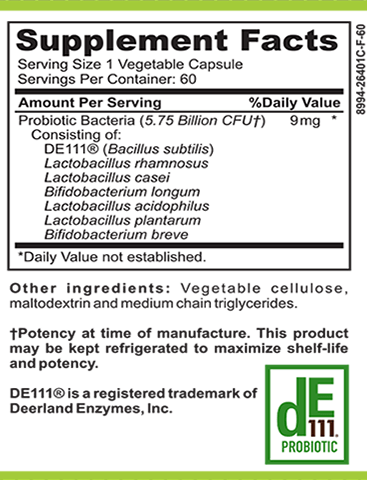

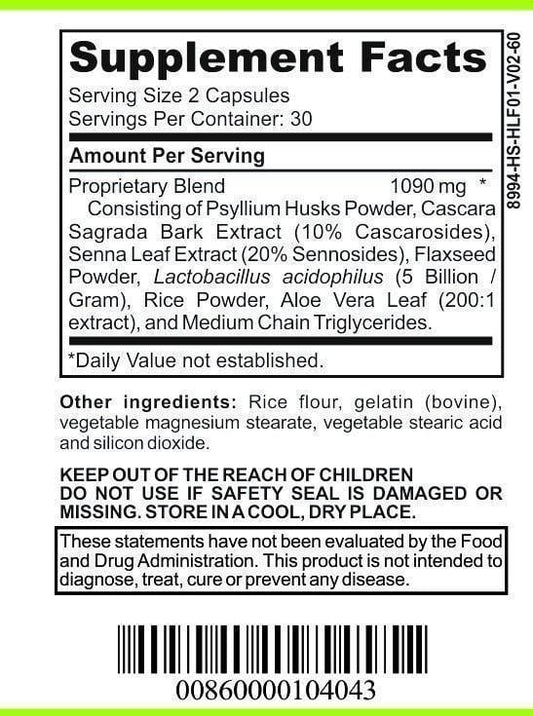

What makes oligosaccharides particularly valuable is their prebiotic nature. Unlike probiotics (which are live beneficial bacteria), prebiotics serve as food for these beneficial microorganisms already residing in your gut. When oligosaccharides reach your large intestine, they're fermented by gut bacteria, producing short-chain fatty acids that nourish colon cells and create an environment where beneficial bacteria can thrive.

This prebiotic effect explains why many functional foods and supplements now deliberately include oligosaccharides as ingredients. Their ability to selectively stimulate the growth of beneficial bacteria like Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli makes them powerful tools for gut health management.

1. Onions: The Everyday Oligosaccharide Powerhouse

Onions are perhaps the most ubiquitous source of oligosaccharides in the global diet. These kitchen staples contain significant amounts of fructooligosaccharides (FOS), particularly inulin. A typical onion contains between 1-7% of its fresh weight as FOS, with red onions generally containing higher concentrations than white varieties.

The distinctive pungent flavor of onions comes from sulfur compounds, but it's the oligosaccharides that contribute to both their health benefits and the digestive discomfort some people experience after consuming them. When cooking onions, some oligosaccharides break down, which is why caramelized or sautéed onions may be better tolerated by sensitive individuals than raw ones.

Culinary Versatility and Oligosaccharide Content

Different onion preparations affect their oligosaccharide content. Raw onions contain the highest levels, while long, slow cooking partially breaks down these compounds. This is why French onion soup, with its deeply caramelized onions, might cause less digestive discomfort than a raw onion salad. Green onions (scallions) contain lower amounts, making them a milder alternative for those sensitive to FODMAPs.

2. Garlic: Small But Mighty

Despite its small serving size, garlic packs a significant oligosaccharide punch. Like its allium cousin the onion, garlic contains substantial amounts of fructooligosaccharides. About 15-16% of garlic's dry weight consists of these prebiotic fibers, with fresh garlic containing around 1-2% FOS by weight.

Garlic's reputation as a health food is partly due to these oligosaccharides, along with its sulfur compounds like allicin. Research suggests that garlic's prebiotic effects may contribute to its cholesterol-lowering and immune-enhancing properties.

Aged Garlic and Oligosaccharides

Interestingly, the aging process used to create black garlic modifies its oligosaccharide profile. The Maillard reaction that occurs during aging converts some simple sugars and creates new compounds, potentially enhancing the prebiotic effects. This might explain why some people with FODMAP sensitivities can better tolerate aged garlic products than fresh garlic.

3. Legumes: Beans, Lentils, and Chickpeas

The connection between beans and digestive gas is well-known in popular culture, and oligosaccharides are the primary culprits. Legumes contain substantial amounts of galactooligosaccharides (GOS), particularly raffinose, stachyose, and verbascose. These compounds make up about 2-6% of the dry weight of most beans.

Chickpeas, black beans, kidney beans, and lentils are particularly rich sources. A single cup of cooked beans can provide 2-3 grams of oligosaccharides, making them one of the most concentrated dietary sources.

Reducing Oligosaccharide Content in Legumes

For those who experience digestive discomfort from beans, certain preparation methods can reduce their oligosaccharide content. Soaking dried beans for 8-12 hours and discarding the soaking water can remove some water-soluble oligosaccharides. Sprouting legumes before cooking also activates enzymes that break down these compounds. Additionally, using a pressure cooker can be more effective at reducing oligosaccharide content than conventional boiling.

Lentil Varieties and Their Oligosaccharide Profiles

Different lentil varieties contain varying levels of oligosaccharides. Red lentils generally have lower levels than green or brown varieties, making them potentially more digestible for sensitive individuals. This variation extends to other legumes as well - navy beans and lima beans typically contain higher oligosaccharide concentrations than black beans or pinto beans.

4. Wheat and Rye Products

Whole grain wheat products contain moderate amounts of fructooligosaccharides, primarily in the form of fructans. These compounds are concentrated in the bran portion of the grain, which is why whole wheat products contain significantly more oligosaccharides than refined wheat products. A slice of whole wheat bread typically contains about 0.5-1 gram of fructans.

Rye contains even higher levels of fructans than wheat, making rye bread and crackers particularly rich sources of these prebiotics. This higher fructan content contributes to rye's distinctive flavor profile and its reputation for supporting digestive health.

Sourdough Fermentation and Oligosaccharides

Traditional sourdough fermentation partially breaks down the fructans in wheat and rye. The lactic acid bacteria and wild yeasts in sourdough starter consume some of these oligosaccharides during the long fermentation process. This is why many people with mild fructan sensitivity can tolerate properly fermented sourdough bread better than conventional bread. Authentic sourdough bread requires a long fermentation period (often 24+ hours) to achieve significant fructan reduction.

5. Asparagus: The Spring Oligosaccharide Source

Asparagus stands out among vegetables for its high inulin content. Fresh asparagus contains approximately 2-3% inulin by weight, with levels varying by growing conditions and variety. The oligosaccharide content is highest in the stalk rather than the tips, which is why some people experience more digestive symptoms from eating the tougher bottom portions.

Beyond its oligosaccharide content, asparagus provides a unique combination of antioxidants and anti-inflammatory compounds. The prebiotic effects of asparagus may enhance the bioavailability of these other beneficial compounds.

White vs. Green Asparagus

White asparagus, grown underground to prevent chlorophyll development, contains slightly different oligosaccharide profiles than green asparagus. The lack of sunlight exposure affects the plant's carbohydrate metabolism, resulting in subtle differences in fructan content and structure. Some studies suggest white asparagus may have slightly lower oligosaccharide levels, though both varieties remain excellent prebiotic sources.

6. Jerusalem Artichokes: The Inulin Champion

Despite their name, Jerusalem artichokes (also called sunchokes) are neither from Jerusalem nor related to artichokes. These knobby tubers are actually part of the sunflower family and contain the highest concentration of inulin of any food source - up to 20% of their fresh weight. This extraordinary level makes them both a powerful prebiotic and potentially challenging for sensitive digestive systems.

The inulin in Jerusalem artichokes has a particularly complex structure with a high degree of polymerization, meaning it's especially resistant to digestion and provides sustained fermentation in the colon. This explains both their reputation for causing flatulence and their effectiveness as a prebiotic.

Cooking Methods and Digestibility

The digestive effects of Jerusalem artichokes can be moderated through cooking methods. Slow roasting or extended boiling partially breaks down the inulin into shorter-chain fructans and simple fructose. Adding a small amount of acid (like lemon juice) to cooking water may enhance this breakdown. For those new to Jerusalem artichokes, starting with small portions and gradually increasing intake allows the gut microbiome to adapt to these potent prebiotics.

7. Chicory Root: The Commercial Oligosaccharide Source

Chicory root is the primary commercial source of inulin and fructooligosaccharides used in food manufacturing. With up to 20% of its dry weight as inulin, chicory root extract is commonly added to foods marketed for digestive health. If you've seen "chicory root fiber" or "inulin" on ingredient lists of protein bars, yogurts, or breakfast cereals, you're encountering deliberately added oligosaccharides.

Beyond its use as an extract, roasted chicory root has historically been used as a coffee substitute or extender, particularly during times of coffee scarcity. This beverage naturally contains significant oligosaccharides, contributing to its mild laxative effect.

Chicory in Processed Foods

Food manufacturers often add chicory-derived inulin to products for multiple purposes. Beyond the prebiotic benefits, inulin provides mild sweetness with fewer calories than sugar, improves texture in low-fat products, and allows for "high fiber" claims on packaging. The amount added to commercial products typically ranges from 1-5 grams per serving, carefully calibrated to provide benefits without causing excessive digestive symptoms.

8. Bananas: The Ripeness Factor

Bananas offer an interesting case study in how oligosaccharide content changes with ripening. Unripe (green) bananas contain significant amounts of resistant starch and fructooligosaccharides. As bananas ripen, these complex carbohydrates gradually convert to simpler sugars, reducing the oligosaccharide content.

A green banana may contain 1-2 grams of fructooligosaccharides, while a fully ripened banana contains significantly less. This transformation explains why green bananas have a stronger prebiotic effect but may cause more digestive symptoms in sensitive individuals compared to their riper counterparts.

Banana Flour: Concentrated Oligosaccharides

Banana flour, made from dried green bananas, has gained popularity as a resistant starch and oligosaccharide source. Used as an alternative flour in baking or added to smoothies, it provides concentrated prebiotic benefits. Just two tablespoons of banana flour can provide similar prebiotic effects to a whole green banana, making it a convenient option for those seeking to increase their prebiotic intake.

9. Apples: Common Fruit with Hidden Benefits

Apples contain moderate amounts of fructooligosaccharides, primarily in the form of fructans. A medium apple provides approximately 0.5-1 gram of these prebiotics. The oligosaccharide content is concentrated in the flesh rather than the skin, though the skin contains valuable polyphenols with their own health benefits.

Different apple varieties contain varying levels of oligosaccharides. Generally, sweeter varieties like Gala and Fuji contain lower levels than tarter varieties like Granny Smith. This variation partly explains why some people with fructan sensitivity may tolerate certain apple varieties better than others.

Processed Apple Products

Apple juice typically contains fewer oligosaccharides than whole apples, as some of these compounds remain in the pulp during juicing. Conversely, applesauce retains most of the original oligosaccharide content. Fermented apple products like hard cider contain minimal oligosaccharides, as the fermentation process consumes these carbohydrates.

10. Artichokes: Not Just Heart-Healthy

Globe artichokes (the familiar flower-like vegetable, distinct from Jerusalem artichokes) contain significant amounts of inulin and fructooligosaccharides. A medium artichoke provides approximately 2-3 grams of these prebiotics, concentrated in the heart and the fleshy base of the leaves.

Beyond their oligosaccharide content, artichokes contain unique polyphenol compounds like cynarin that support liver function and digestion. The combination of these bioactive compounds with prebiotics may create synergistic health effects, particularly for digestive and metabolic health.

Artichoke Extract Supplements

Concentrated artichoke extract is available as a dietary supplement, often marketed for liver support and digestive health. These supplements typically standardize both the oligosaccharide content and the cynarin content, providing a more potent dose than would be practical to obtain from eating whole artichokes. For those seeking the benefits without the preparation challenges of fresh artichokes, these supplements offer a convenient alternative.

Incorporating Oligosaccharides Into Your Diet

When adding oligosaccharide-rich foods to your diet, gradual introduction is key. Starting with small portions and slowly increasing intake allows your gut microbiome to adapt, potentially reducing digestive discomfort. Combining these foods with adequate hydration can also help minimize symptoms like bloating or gas.

For those with irritable bowel syndrome or FODMAP sensitivities, working with a registered dietitian can help identify which oligosaccharide sources are best tolerated. Many people find they can include moderate amounts of certain oligosaccharide-rich foods without symptoms, particularly when properly prepared.

Cooking Methods That Affect Oligosaccharide Content

Various cooking techniques can modify the oligosaccharide content of foods. Extended boiling in water can leach some water-soluble oligosaccharides into the cooking liquid. Fermentation, whether through sourdough bread making or traditional preparation of foods like kimchi, partially breaks down these compounds. For those seeking to maximize oligosaccharide intake, gentle cooking methods like steaming or quick sautéing help preserve these beneficial compounds.

Understanding the oligosaccharide content of common foods empowers you to make informed dietary choices. Whether you're looking to support gut health through prebiotic intake or manage digestive sensitivities, this knowledge provides a practical foundation for personalized nutrition. By thoughtfully incorporating these foods into your diet, you can harness the potential benefits of oligosaccharides while minimizing any unwanted effects.