The Digestive Enzymes: Essential Functions and Health Benefits

The Digestive Enzymes: Essential Functions and Health Benefits

Our bodies are remarkable machines, constantly working behind the scenes to keep us functioning optimally. Among the unsung heroes of this intricate system are digestive enzymes – specialized proteins that break down the food we eat into nutrients our bodies can absorb and use. Without these powerful catalysts, even the healthiest diet would fail to nourish us properly. Understanding how digestive enzymes work can help us make informed decisions about our diet, supplementation, and overall digestive health.

What Are Digestive Enzymes?

Digestive enzymes are specialized proteins that act as biological catalysts, speeding up chemical reactions in the body without being consumed in the process. These remarkable molecules are essential for breaking down the complex molecules in our food into smaller, absorbable components. Each enzyme is highly specific, designed to break down particular types of nutrients, working like specialized keys that fit only certain locks.

Our bodies produce most digestive enzymes naturally, secreting them from various organs along the digestive tract. The process begins in the mouth and continues through the stomach, pancreas, and small intestine. Some enzymes are embedded in the intestinal walls, while others are released into the digestive tract to interact with food as it passes through.

The Major Classes of Digestive Enzymes

There are three primary categories of digestive enzymes, each responsible for breaking down different macronutrients in our diet:

Amylases break down complex carbohydrates like starches and glycogen into simpler sugars. This process begins in the mouth with salivary amylase and continues in the small intestine with pancreatic amylase. When you notice that a piece of bread starts tasting sweeter the longer you chew it, you're experiencing amylase in action, converting starch to sugar.

Proteases (also called proteolytic enzymes) break down proteins into amino acids and smaller peptides. This process primarily occurs in the stomach with pepsin and continues in the small intestine with enzymes like trypsin and chymotrypsin from the pancreas. Without proteases, the protein in your chicken breast or tofu would remain unusable by your body.

Lipases break down dietary fats (lipids) into fatty acids and glycerol. Produced mainly by the pancreas and released into the small intestine, lipases work with bile from the liver to digest the fats in foods like avocados, nuts, and oils. Proper fat digestion is crucial not just for energy but also for absorbing fat-soluble vitamins like A, D, E, and K.

Other Important Digestive Enzymes

Beyond the three major classes, our digestive system employs several other specialized enzymes to handle specific components of our diet. Lactase breaks down lactose (milk sugar) into glucose and galactose. People with lactose intolerance have insufficient lactase, leading to digestive discomfort when consuming dairy products. Sucrase converts sucrose (table sugar) into glucose and fructose, while maltase breaks down maltose (malt sugar) into glucose molecules. Nucleases handle the digestion of nucleic acids from DNA and RNA in our food.

The Digestive Enzyme Journey

The digestion process is a carefully orchestrated journey that begins even before the first bite. The mere sight, smell, or thought of food triggers the digestive system to prepare for incoming nourishment. This preparation includes the secretion of enzymes at various points along the digestive tract.

From Mouth to Stomach

Digestion begins in the mouth, where salivary amylase starts breaking down starches as you chew. This is why thoroughly chewing your food is so important – it not only mechanically breaks down food but also allows more time for these initial enzymes to work. The partially digested food then travels down the esophagus to the stomach.

In the stomach, food encounters a highly acidic environment where pepsin – activated by stomach acid – begins protein digestion. The stomach also produces a small amount of gastric lipase to begin fat breakdown, though this enzyme plays a minor role compared to pancreatic lipase later in the process. The stomach churns and mixes food with these enzymes and acids, creating a semi-liquid mixture called chyme.

The Small Intestine: Digestion Central

The small intestine is where most digestion and nutrient absorption occurs. As chyme enters the small intestine, it triggers the release of hormones that signal the pancreas to secrete its powerful digestive enzymes. The pancreas delivers amylase, lipase, and proteases (trypsin and chymotrypsin) through the pancreatic duct into the duodenum – the first section of the small intestine.

Simultaneously, the liver produces bile, which is stored in the gallbladder until needed. Bile doesn't contain enzymes but helps emulsify fats – breaking large fat globules into smaller droplets that lipase can more efficiently digest. The intestinal lining itself produces additional enzymes, including lactase, sucrase, and maltase, which complete the breakdown of carbohydrates into simple sugars.

As food moves through the small intestine, these enzymes break nutrients down into their smallest components: proteins into amino acids, carbohydrates into simple sugars, and fats into fatty acids and glycerol. These nutrients are then absorbed through the intestinal wall into the bloodstream, where they can be transported throughout the body for use or storage.

Common Digestive Enzyme Disorders

When the production or function of digestive enzymes is compromised, various digestive disorders can result. These conditions can significantly impact quality of life and nutritional status if not properly addressed.

Enzyme Deficiencies

Lactose intolerance is perhaps the most well-known enzyme deficiency, affecting approximately 65% of the global population. It occurs when the body produces insufficient lactase to digest lactose in dairy products, leading to symptoms like bloating, gas, and diarrhea after consuming milk products. The prevalence varies widely by ethnicity and geographic region, with some populations having rates as high as 90%.

Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI) is a more serious condition where the pancreas fails to produce enough digestive enzymes. This can result from chronic pancreatitis, cystic fibrosis, pancreatic cancer, or pancreatic surgery. Symptoms include steatorrhea (fatty, foul-smelling stools), weight loss despite normal eating, and malnutrition. Treatment typically involves pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (PERT) with each meal.

Digestive Enzymes and Chronic Conditions

Several chronic health conditions are associated with digestive enzyme issues. Celiac disease, an autoimmune disorder triggered by gluten, damages the intestinal lining where many digestive enzymes are produced. This damage can lead to secondary enzyme deficiencies and malabsorption of nutrients. Inflammatory bowel diseases like Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis can also impair enzyme production and function due to inflammation along the digestive tract.

Aging naturally reduces digestive enzyme production, which may contribute to the increased digestive complaints among older adults. Some research suggests that chronic stress may also impair digestive enzyme secretion by activating the "fight or flight" response, which diverts resources away from digestion.

Dietary Sources of Digestive Enzymes

While our bodies produce most of the enzymes we need, certain foods contain natural enzymes that can support digestion. Including these foods in your diet may help complement your body's enzyme production, particularly if you experience occasional digestive discomfort.

Enzyme-Rich Foods

Fresh pineapple contains bromelain, a proteolytic enzyme that helps break down proteins. This is why pineapple has traditionally been used as a meat tenderizer – the bromelain begins breaking down the meat's protein structures before you even eat it. Papaya contains a similar enzyme called papain, which is also effective at protein digestion and is often used in commercial meat tenderizers.

Fermented foods like sauerkraut, kimchi, kefir, and yogurt contain beneficial bacteria that produce enzymes as part of the fermentation process. These foods provide not only enzymes but also probiotics that support overall gut health. Raw honey contains several enzymes, including amylase, which helps break down carbohydrates. However, heating honey above 118°F (48°C) can destroy these enzymes, so it's best consumed raw.

Mangoes, especially when ripe, contain amylases that help break down carbohydrates. Avocados are rich in lipase, which aids fat digestion. Bananas contain amylases and glucosidases that help break down complex carbs and release antioxidants.

Digestive Enzyme Supplements

For those with diagnosed enzyme deficiencies or certain digestive conditions, enzyme supplements can be valuable therapeutic tools. These supplements are available in various formulations designed to address specific digestive needs.

Types of Enzyme Supplements

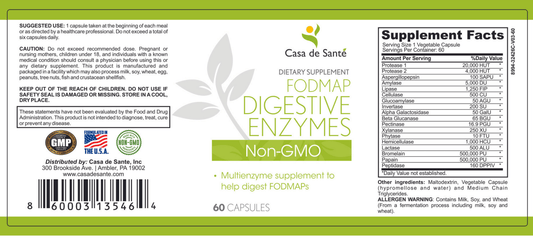

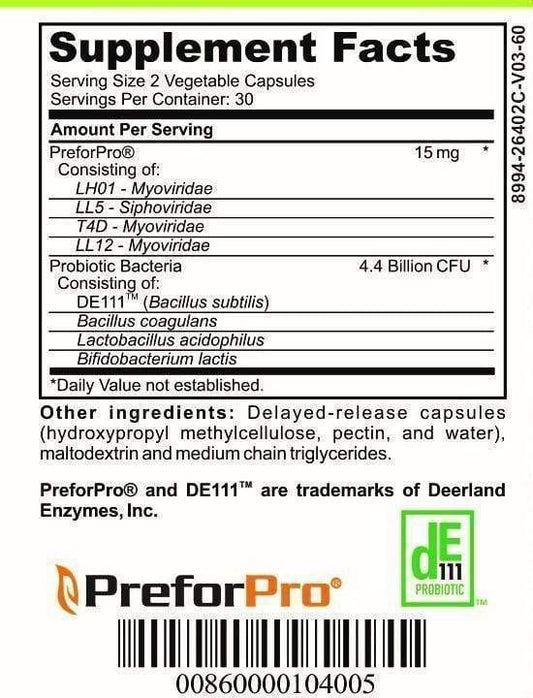

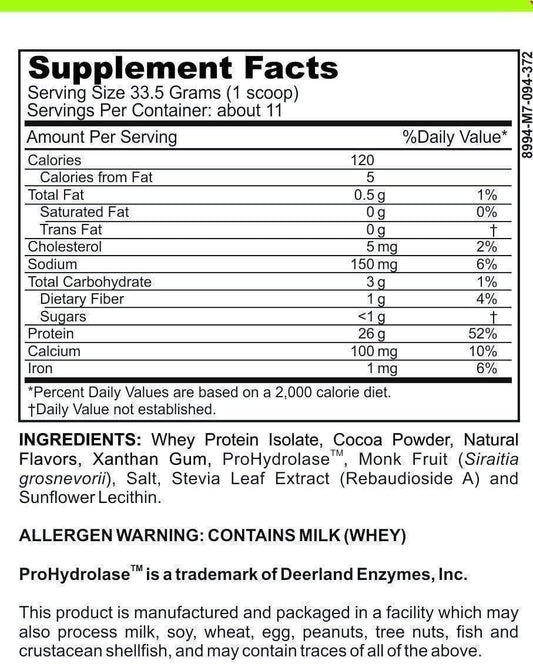

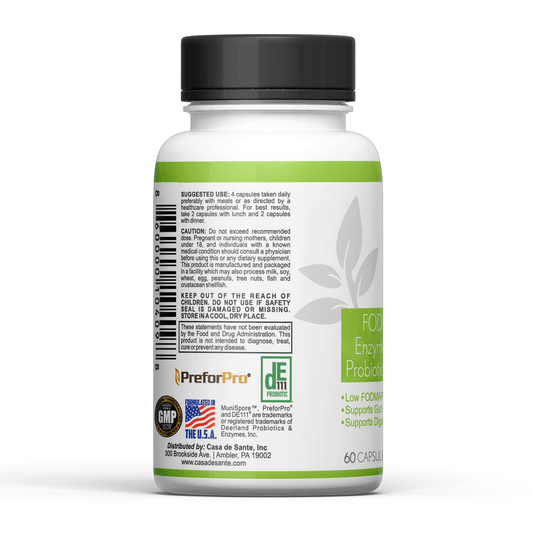

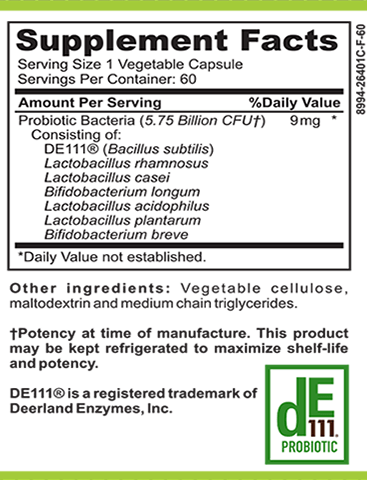

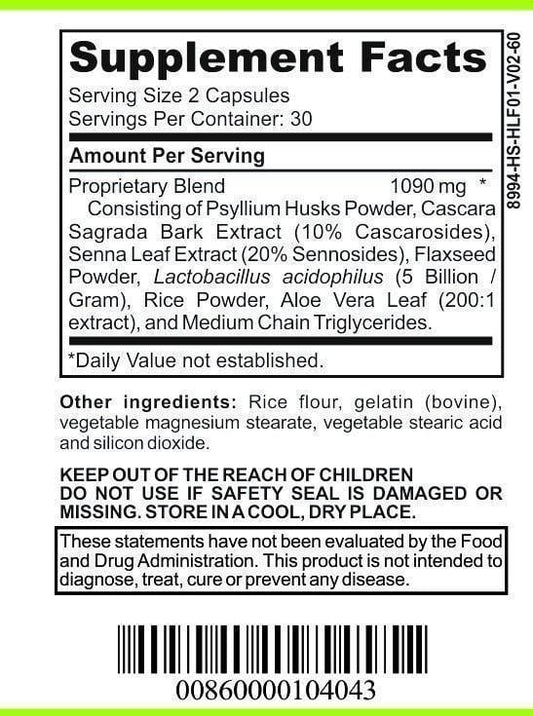

Broad-spectrum digestive enzyme supplements typically contain a mixture of amylase, protease, and lipase, often along with additional enzymes like lactase, cellulase (which breaks down plant fiber), and alpha-galactosidase (which helps digest complex sugars in beans and cruciferous vegetables). These formulations aim to support overall digestion of a mixed diet.

Specialized enzyme supplements target specific digestive challenges. Lactase supplements help those with lactose intolerance digest dairy products. Alpha-galactosidase supplements (like Beano) help prevent gas and bloating from beans and certain vegetables. Pancreatic enzyme replacement products, available by prescription, contain concentrated pancreatic enzymes for those with pancreatic insufficiency.

Choosing and Using Supplements Wisely

When considering enzyme supplements, it's important to consult with a healthcare provider, especially if you have ongoing digestive symptoms. Persistent digestive issues could indicate an underlying condition that requires proper diagnosis and treatment. Self-diagnosing and treating with supplements might mask important symptoms or delay necessary medical care.

Look for quality products from reputable manufacturers that specify the activity units of each enzyme rather than just the weight. Activity units (like DU for amylase or FIP for lipase) indicate the enzyme's potency. Follow dosage instructions carefully, as more isn't necessarily better with enzymes. Most supplements should be taken just before meals to ensure they're present when food enters the digestive tract.

Conclusion

Digestive enzymes are remarkable biological tools that make nutrition possible. From the moment food enters our mouths until nutrients are absorbed in the intestines, these specialized proteins work tirelessly to break down our meals into usable components. Understanding how these enzymes function can help us make better choices about our diet, recognize potential digestive issues, and know when supplementation might be beneficial.

Whether you're experiencing digestive challenges or simply interested in optimizing your nutritional intake, appreciating the role of digestive enzymes offers valuable insights into how your body processes the foods you eat. By supporting your natural enzyme production through diet, lifestyle, and, when necessary, appropriate supplementation, you can help ensure that your digestive system functions at its best – turning the foods you enjoy into the nutrients your body needs to thrive.