10 Common Foods High in Fructans: A Comprehensive Guide

10 Common Foods High in Fructans: A Comprehensive Guide

Navigating dietary restrictions can be challenging, especially when it comes to understanding which foods contain specific compounds that might trigger digestive issues. Fructans, a type of carbohydrate found in many common foods, have gained attention due to their potential role in causing symptoms for people with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and other digestive sensitivities. This comprehensive guide explores ten everyday foods high in fructans, helping you make informed choices about your diet.

What Are Fructans and Why Do They Matter?

Fructans are chains of fructose molecules that the human small intestine cannot fully digest. Instead, they travel to the large intestine where gut bacteria ferment them, potentially causing gas, bloating, and other digestive discomfort in sensitive individuals. Fructans belong to a group of carbohydrates known as FODMAPs (Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides, and Polyols), which are commonly restricted in diets designed to manage IBS symptoms.

Despite their potential to cause digestive issues in some people, fructans aren't inherently unhealthy. In fact, they function as prebiotics, feeding beneficial gut bacteria and supporting overall digestive health in those who can tolerate them. This dual nature makes understanding fructan-containing foods particularly important for personalized nutrition.

The FODMAP Connection

The Low FODMAP diet, developed by researchers at Monash University in Australia, has gained significant traction as an evidence-based approach to managing IBS symptoms. Fructans represent one of the key FODMAP groups that may need to be temporarily restricted during the elimination phase of this diet. Identifying high-fructan foods is therefore crucial for anyone following this therapeutic eating plan.

Wheat and Wheat-Based Products

Wheat is perhaps the most ubiquitous source of fructans in the Western diet. Found in bread, pasta, crackers, cookies, and countless other staple foods, wheat contributes significantly to many people's daily fructan intake. The fructan content in wheat products varies based on the specific type of wheat and processing methods, but generally, wheat-based foods represent one of the most consistent sources of these carbohydrates.

Interestingly, the rising popularity of gluten-free diets may inadvertently help some people reduce their fructan intake. Many individuals who report feeling better on a gluten-free diet, despite not having celiac disease, may actually be responding to reduced fructan consumption rather than gluten elimination. This phenomenon has led some researchers to suggest that non-celiac gluten sensitivity might, in some cases, actually be fructan sensitivity.

Bread and Baked Goods

Among wheat products, bread is particularly high in fructans. Traditional wheat bread, especially those made with shorter fermentation times, can contain significant amounts. Sourdough bread, however, may be better tolerated by some individuals because the longer fermentation process allows bacteria to pre-digest some of the fructans. Pastries, muffins, cakes, and other wheat-based baked goods also contribute substantially to fructan intake.

Pasta and Noodles

Wheat pasta is another major source of fructans in many diets. Regular spaghetti, macaroni, and other wheat-based noodles contain these fermentable carbohydrates. Rice-based pasta alternatives offer a lower-fructan option for those looking to reduce their intake while still enjoying pasta dishes. Egg noodles, while still containing wheat, may have a slightly lower fructan content due to the dilution effect of the eggs in the recipe.

Onions: A Fructan Powerhouse

Onions stand out as one of the most concentrated sources of fructans in the common diet. All varieties of onions—red, white, yellow, and green—contain substantial amounts of these carbohydrates. What makes onions particularly challenging for those on a low-fructan diet is their widespread use as a flavor base in countless recipes, soups, sauces, and prepared foods.

The fructan content in onions is highest in the bulb portion and decreases toward the green tops. This means that people with severe fructan sensitivity might be able to use the green parts of spring onions (scallions) as a flavor alternative. Additionally, infusing cooking oil with onion flavor (then removing the solid pieces) can provide onion taste without the fructans, as these compounds are not fat-soluble.

Onion Derivatives and Hidden Sources

Onion powder, onion salt, and other onion-derived ingredients are concentrated sources of fructans and appear frequently in commercial seasonings, spice blends, and processed foods. Reading ingredient labels becomes essential for those trying to avoid fructans, as onion can be hidden in everything from salad dressings to potato chips, soup bases, and marinades.

Garlic: Small But Mighty

Like its allium relative onion, garlic packs a significant fructan punch in a small package. Just one clove of garlic contains enough fructans to trigger symptoms in sensitive individuals. Given garlic's potent flavor and widespread culinary use across virtually all global cuisines, it presents a particular challenge for those following a low-fructan diet.

Garlic-infused oil offers a workable solution for many people, as the flavor compounds in garlic are oil-soluble while the fructans remain in the solid garlic pieces. By slowly heating garlic in oil and then straining out the solids, it's possible to capture the distinctive garlic flavor without the problematic carbohydrates.

Garlic in Processed Foods

Like onion, garlic appears frequently in processed and prepared foods, often listed simply as "spices" or "natural flavors" on ingredient labels. This ubiquity makes restaurant dining and convenience food consumption particularly challenging for those with fructan sensitivity. Garlic powder, garlic salt, and garlic supplements contain concentrated amounts of fructans and should be approached with caution by sensitive individuals.

Legumes: Beans, Lentils, and Chickpeas

Legumes represent another significant source of fructans in many diets. Chickpeas, lentils, kidney beans, black beans, and soybeans all contain varying amounts of these fermentable carbohydrates. The fructan content can differ based on the specific variety and preparation method, with some legumes containing more than others.

Despite their fructan content, legumes offer impressive nutritional benefits, including protein, fiber, vitamins, and minerals. For this reason, completely eliminating them from the diet may not be necessary or beneficial for everyone. Some people find that smaller portions of certain legumes can be tolerated, especially when properly prepared through soaking and thorough cooking.

Preparation Methods Matter

The way legumes are prepared can influence their digestibility and fructan content. Traditional preparation methods like soaking dried beans overnight, discarding the soaking water, and cooking thoroughly may help reduce the FODMAP content. Additionally, canned legumes that have been rinsed thoroughly may be better tolerated by some individuals than their dried counterparts, as some of the fructans leach into the canning liquid.

Fruits: Apples, Pears, and Watermelon

While fruits are often associated with fructose rather than fructans, several common fruits do contain notable amounts of these carbohydrate chains. Apples, pears, watermelon, and nectarines are among the fruits that contain both excess fructose and fructans, potentially causing double trouble for those with sensitivities.

The fructan content in fruits can vary significantly based on ripeness, with some fruits developing higher levels as they ripen. This explains why some people might tolerate less ripe fruit better than very ripe specimens. Additionally, cooking fruit can sometimes alter its FODMAP content, making cooked apples potentially more digestible than raw ones for some individuals.

Dried Fruits: Concentrated Sources

The dehydration process concentrates all components in fruit, including fructans. This makes dried fruits like dates, figs, and raisins particularly high in these fermentable carbohydrates. Even small portions of these foods can provide a significant fructan load, making them challenging for sensitive individuals to include in their diets.

Artichokes and Asparagus

Among vegetables, artichokes stand out as particularly high in fructans. Both globe artichokes and Jerusalem artichokes (which, despite the name, are not related to globe artichokes but are actually a type of sunflower root) contain substantial amounts of these carbohydrates. Jerusalem artichokes, also called sunchokes, are especially rich in inulin, a type of fructan often used as a prebiotic supplement.

Asparagus also contains significant levels of fructans, particularly in the stalk. The tips may be better tolerated in small amounts by some individuals with mild sensitivity. Both artichokes and asparagus offer impressive nutritional profiles, including antioxidants, vitamins, and minerals, making them valuable additions to the diet for those who can tolerate them.

Rye and Barley

Like wheat, other grains in the grass family, particularly rye and barley, contain substantial amounts of fructans. Rye bread, rye crackers, and foods containing barley (including many beers) can be significant sources of these fermentable carbohydrates. Barley is also commonly used as a food additive in the form of barley malt, appearing in cereals, candies, and other processed foods.

For those looking to reduce fructan intake while maintaining whole grain consumption, options like rice, corn, oats, and quinoa generally contain lower amounts of these carbohydrates. However, portion size remains important, as even lower-fructan grains can contribute to overall FODMAP load when consumed in large quantities.

Managing Fructan Intake: Practical Strategies

Understanding which foods contain fructans is just the first step in managing sensitivity to these carbohydrates. Working with a registered dietitian, particularly one experienced in the low FODMAP approach, can help create a personalized plan that identifies trigger foods while maintaining nutritional adequacy and quality of life.

Many people find that they can tolerate small amounts of fructan-containing foods, especially when spread throughout the day rather than consumed in one sitting. This concept of "threshold" is important—sensitivity is rarely all-or-nothing, and finding your personal tolerance level can expand dietary options significantly.

The Reintroduction Phase

After an initial period of restriction, systematically reintroducing fructan-containing foods in measured amounts can help determine personal tolerance thresholds. This process, ideally guided by a healthcare professional, allows for the development of a more liberal, individualized long-term eating pattern that minimizes symptoms while maximizing dietary variety and nutritional intake.

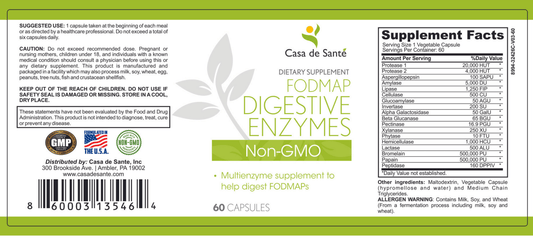

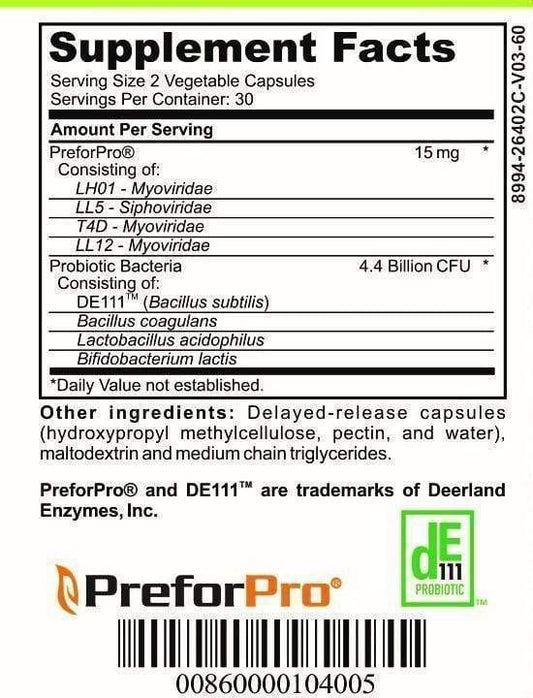

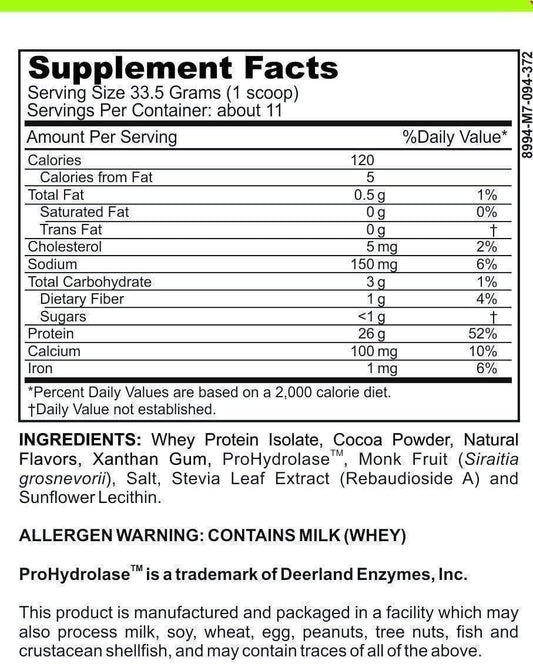

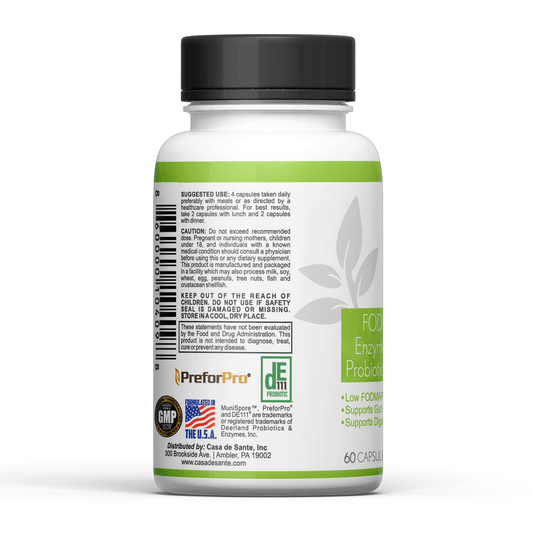

Enzyme Supplements

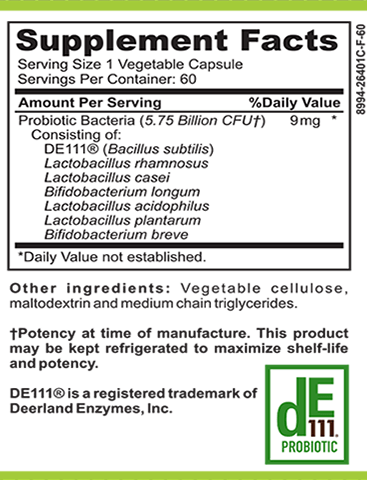

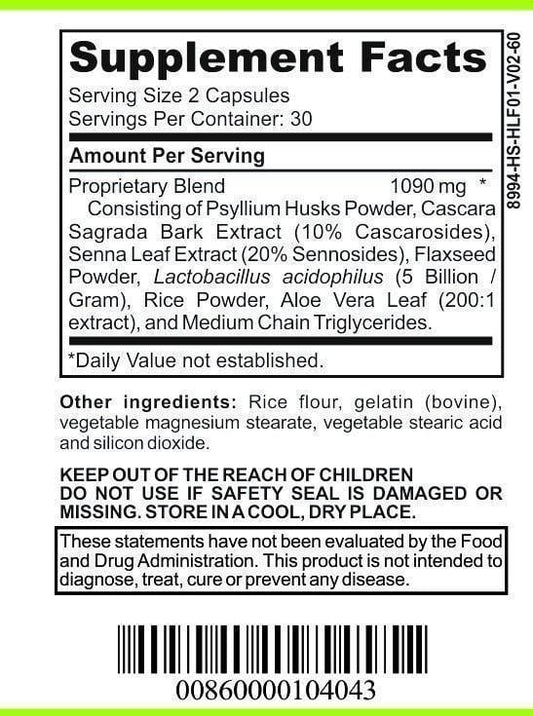

Some preliminary research suggests that certain enzyme supplements might help break down fructans in the digestive tract, potentially reducing symptoms in sensitive individuals. While the evidence is still emerging, products containing alpha-galactosidase or other specific enzymes may offer additional support for some people when consuming moderate amounts of fructan-containing foods.

Conclusion

Navigating a diet with fructan sensitivity requires knowledge, planning, and patience. The ten common foods highlighted in this guide—wheat products, onions, garlic, legumes, certain fruits, artichokes, asparagus, rye, and barley—represent major sources of dietary fructans, but they certainly don't constitute an exhaustive list. By understanding these key contributors and working with healthcare professionals, most people can develop a personalized approach that balances symptom management with nutritional needs and food enjoyment.

Remember that dietary needs are highly individual, and what triggers symptoms in one person may be perfectly tolerable for another. The goal isn't necessarily complete elimination of fructan-containing foods, but rather finding your personal balance point that supports both digestive comfort and overall health.