Intestinal Mucosa: Sibo Explained

Intestinal Mucosa: Sibo Explained

The intestinal mucosa, a critical component of the human digestive system, plays a vital role in the absorption of nutrients, the production of certain vitamins, and the protection against harmful pathogens. This article delves into the intricate workings of the intestinal mucosa and its relation to Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO), a condition characterized by an excessive amount of bacteria in the small intestine.

Understanding the complex relationship between the intestinal mucosa and SIBO can provide valuable insights into the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of this condition. This article aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of these topics, exploring the structure and function of the intestinal mucosa, the causes and symptoms of SIBO, and the impact of SIBO on the intestinal mucosa.

Understanding the Intestinal Mucosa

The intestinal mucosa, the innermost layer of the gastrointestinal tract, is a mucous membrane that lines the small and large intestines. It is composed of three layers: the epithelium, the lamina propria, and the muscularis mucosae. Each of these layers plays a unique role in the functioning of the digestive system.

The epithelium, the outermost layer of the intestinal mucosa, is responsible for the absorption of nutrients from the food we eat. The lamina propria, located beneath the epithelium, contains blood vessels and lymphatic vessels that transport nutrients throughout the body. The muscularis mucosae, the innermost layer, facilitates the movement of food through the digestive tract.

Role of the Intestinal Mucosa

The intestinal mucosa serves several vital functions in the body. First, it acts as a barrier, protecting the body from harmful substances and pathogens. The epithelial cells of the intestinal mucosa are tightly packed together, preventing bacteria and toxins from entering the bloodstream. Additionally, these cells produce mucus, which traps and neutralizes harmful substances.

Second, the intestinal mucosa is responsible for the absorption of nutrients. The epithelial cells have finger-like projections called villi and microvilli, which increase the surface area for absorption. These structures allow for the efficient absorption of nutrients, including carbohydrates, proteins, and fats.

Impact of the Intestinal Mucosa on Immunity

The intestinal mucosa also plays a crucial role in the immune system. The lamina propria contains immune cells that can identify and destroy harmful pathogens. Furthermore, the intestinal mucosa houses the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), which is the largest collection of lymphoid tissue in the body. The GALT plays a vital role in the immune response, producing antibodies that protect against pathogens.

The intestinal mucosa also produces antimicrobial peptides and secretes IgA antibodies, which neutralize pathogens and prevent them from adhering to the epithelial cells. This immune function of the intestinal mucosa is critical in maintaining the balance of the gut microbiota, preventing the overgrowth of harmful bacteria.

Understanding SIBO

Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) is a condition characterized by an excessive amount of bacteria in the small intestine. While the small intestine does contain bacteria, it is typically present in much lower amounts than in the large intestine. In SIBO, the bacterial population in the small intestine increases significantly, leading to a range of digestive symptoms.

SIBO can be caused by a variety of factors, including slow motility of the small intestine, structural abnormalities in the digestive tract, and certain medical conditions. The symptoms of SIBO can vary widely but often include bloating, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and malnutrition due to poor nutrient absorption.

Causes of SIBO

Several factors can contribute to the development of SIBO. One of the primary causes is a disruption in the normal movement of the small intestine. This can be due to conditions that affect the nerves or muscles of the digestive tract, such as diabetes or scleroderma. Additionally, surgical procedures that alter the structure of the digestive tract, such as gastric bypass surgery, can lead to SIBO.

Other causes of SIBO include immune deficiencies, which can allow bacteria to proliferate, and chronic use of certain medications, such as proton pump inhibitors, which can disrupt the balance of the gut microbiota. Furthermore, conditions that cause inflammation or damage to the intestinal mucosa, such as Crohn's disease or celiac disease, can increase the risk of SIBO.

Symptoms of SIBO

The symptoms of SIBO can be quite varied and often overlap with other digestive disorders, making it challenging to diagnose. Common symptoms include bloating, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and constipation. These symptoms are often related to the overgrowth of bacteria in the small intestine, which can produce gas and interfere with the normal digestion and absorption of nutrients.

Other symptoms of SIBO can include weight loss and malnutrition, due to poor nutrient absorption. Some people with SIBO may also experience fatigue, weakness, and a variety of other non-specific symptoms. In severe cases, SIBO can lead to serious complications, such as vitamin and mineral deficiencies, osteoporosis, and even damage to the nervous system.

SIBO and the Intestinal Mucosa

The relationship between SIBO and the intestinal mucosa is complex and multifaceted. On one hand, damage to the intestinal mucosa can contribute to the development of SIBO. On the other hand, SIBO can cause further damage to the intestinal mucosa, leading to a vicious cycle of inflammation and bacterial overgrowth.

The overgrowth of bacteria in SIBO can damage the epithelial cells of the intestinal mucosa, disrupting the tight junctions between these cells. This can lead to increased intestinal permeability, commonly known as "leaky gut". This increased permeability allows bacteria and toxins to enter the bloodstream, leading to inflammation and a variety of symptoms.

Impact of SIBO on Nutrient Absorption

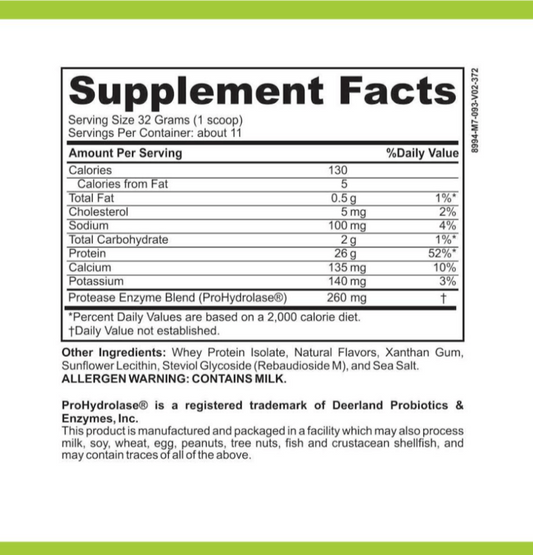

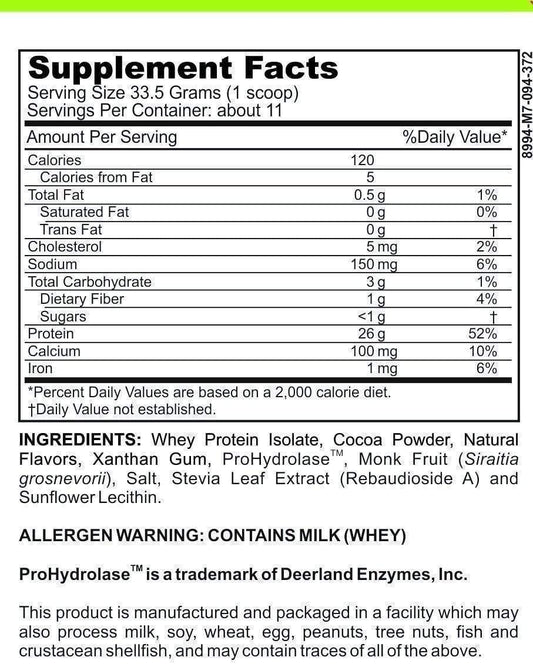

SIBO can significantly impact the absorption of nutrients in the small intestine. The overgrowth of bacteria can interfere with the digestion of food, leading to malabsorption of nutrients. This can result in deficiencies in a variety of nutrients, including vitamins, minerals, and proteins.

Furthermore, the bacteria in SIBO can consume some of the nutrients in the food, further reducing the availability of these nutrients for absorption. This can lead to weight loss and malnutrition, which are common symptoms of SIBO. In severe cases, this malnutrition can lead to serious complications, such as anemia and osteoporosis.

Impact of SIBO on the Immune Function of the Intestinal Mucosa

The overgrowth of bacteria in SIBO can also impact the immune function of the intestinal mucosa. The excessive amount of bacteria can overwhelm the immune cells in the lamina propria, leading to chronic inflammation. This inflammation can damage the intestinal mucosa, further disrupting the barrier function and leading to increased intestinal permeability.

Furthermore, the bacteria in SIBO can alter the balance of the gut microbiota, disrupting the normal immune response. This can lead to an overactive immune response, resulting in further inflammation and damage to the intestinal mucosa. This disruption of the immune function can also increase the risk of other conditions, such as autoimmune diseases and allergies.

Diagnosis and Treatment of SIBO

Diagnosing SIBO can be challenging due to the overlap of symptoms with other digestive disorders. The gold standard for diagnosing SIBO is a small bowel aspirate and culture, which involves taking a sample of fluid from the small intestine and testing it for bacteria. However, this procedure is invasive and not commonly used. More commonly, SIBO is diagnosed using breath tests, which measure the levels of certain gases produced by bacteria in the small intestine.

The treatment of SIBO typically involves antibiotics to reduce the bacterial overgrowth, along with dietary modifications to manage symptoms and prevent recurrence. In some cases, probiotics may be used to restore the balance of the gut microbiota. Additionally, treatment may include addressing any underlying conditions that contributed to the development of SIBO.

Antibiotic Treatment for SIBO

Antibiotics are the primary treatment for SIBO, aiming to reduce the bacterial overgrowth in the small intestine. The choice of antibiotic depends on the specific bacteria present, as determined by the breath test or small bowel aspirate and culture. Commonly used antibiotics for SIBO include rifaximin, neomycin, and metronidazole.

While antibiotics can be effective in reducing the symptoms of SIBO, they do not address the underlying causes of the condition. Therefore, recurrence is common after antibiotic treatment. To prevent recurrence, it is important to address any underlying conditions that contributed to the development of SIBO, such as slow motility or structural abnormalities in the digestive tract.

Dietary Modifications for SIBO

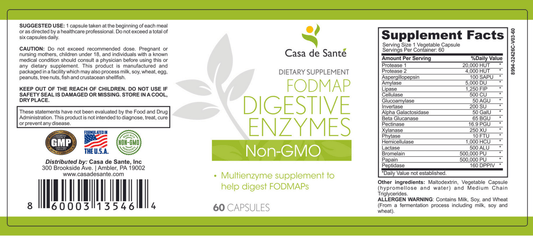

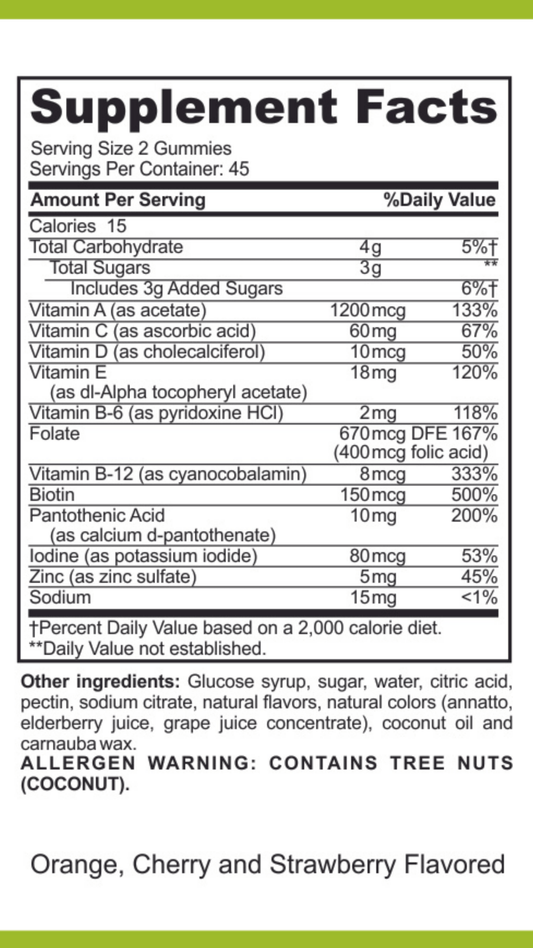

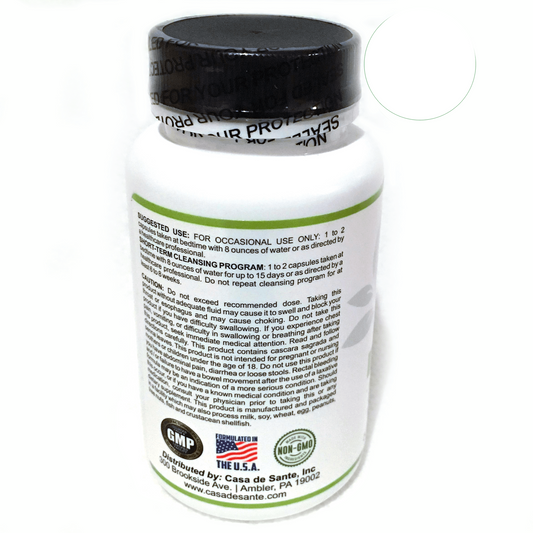

Dietary modifications can play a crucial role in the management of SIBO. The goal of dietary modifications is to reduce the intake of foods that feed the bacteria in the small intestine, thereby reducing bacterial overgrowth. This typically involves a low-FODMAP diet, which restricts the intake of certain types of carbohydrates that are difficult to digest and can feed the bacteria.

In addition to a low-FODMAP diet, other dietary strategies may be beneficial for managing SIBO. These can include a high-fiber diet, which can promote regular bowel movements and reduce the risk of bacterial overgrowth, and a diet rich in fermented foods, which can help restore the balance of the gut microbiota. However, dietary modifications should be individualized, as different people may respond differently to different diets.

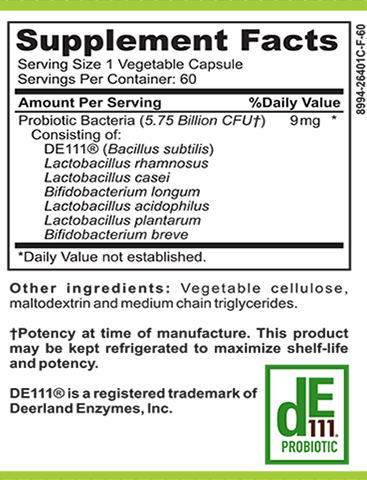

Probiotics for SIBO

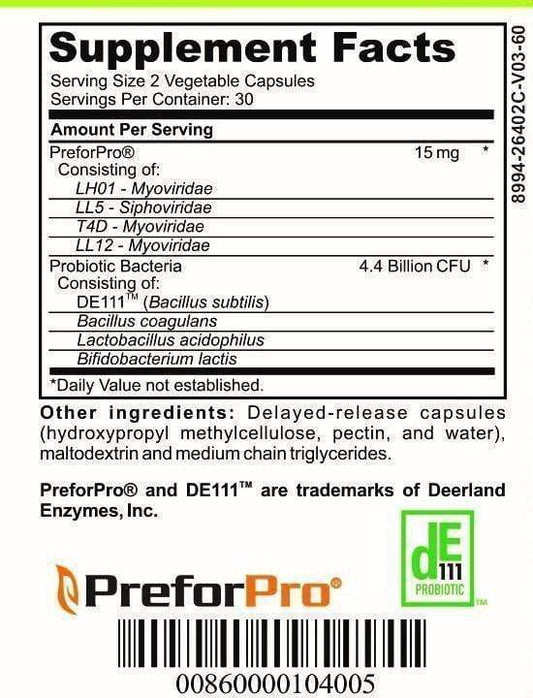

Probiotics, which are beneficial bacteria, may be used as a complementary treatment for SIBO. The goal of probiotic therapy is to restore the balance of the gut microbiota, reducing the overgrowth of harmful bacteria. Probiotics can also enhance the immune function of the intestinal mucosa, helping to prevent recurrence of SIBO.

While the use of probiotics for SIBO is promising, more research is needed to determine the most effective strains and dosages. It is also important to note that probiotics should be used with caution in people with weakened immune systems, as they can potentially cause infections. As with all treatments for SIBO, probiotics should be used under the guidance of a healthcare provider.

Conclusion

The relationship between the intestinal mucosa and SIBO is complex and multifaceted. Understanding this relationship can provide valuable insights into the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of SIBO. While SIBO can be a challenging condition to manage, with the right treatment and lifestyle modifications, it is possible to reduce symptoms and improve quality of life.

As research continues to unravel the intricate workings of the intestinal mucosa and its role in SIBO, it is hoped that this will lead to more effective treatments and prevention strategies. In the meantime, a comprehensive understanding of the intestinal mucosa and SIBO can empower individuals to take control of their digestive health and live a healthier, happier life.